Episode 18: Wright House Murders

If you trace the dark path back through Wright’s life and work, there is a very good reason why he changed his design philosophy so radically. When Frank Lloyd Wright built the home he thought represented his ultimate dream, it became the site of a nightmare he could never escape.

Listen to Learn More about:

The Murderer that killed a family and entire staff in Frank Lloyd Wright's home.

The personal life of architect Frank Lloyd Wright

Architecture like The Guggenheim, Ennis House, and Taliesin

Frank Lloyd Wright's early career and rise to fame

Images:

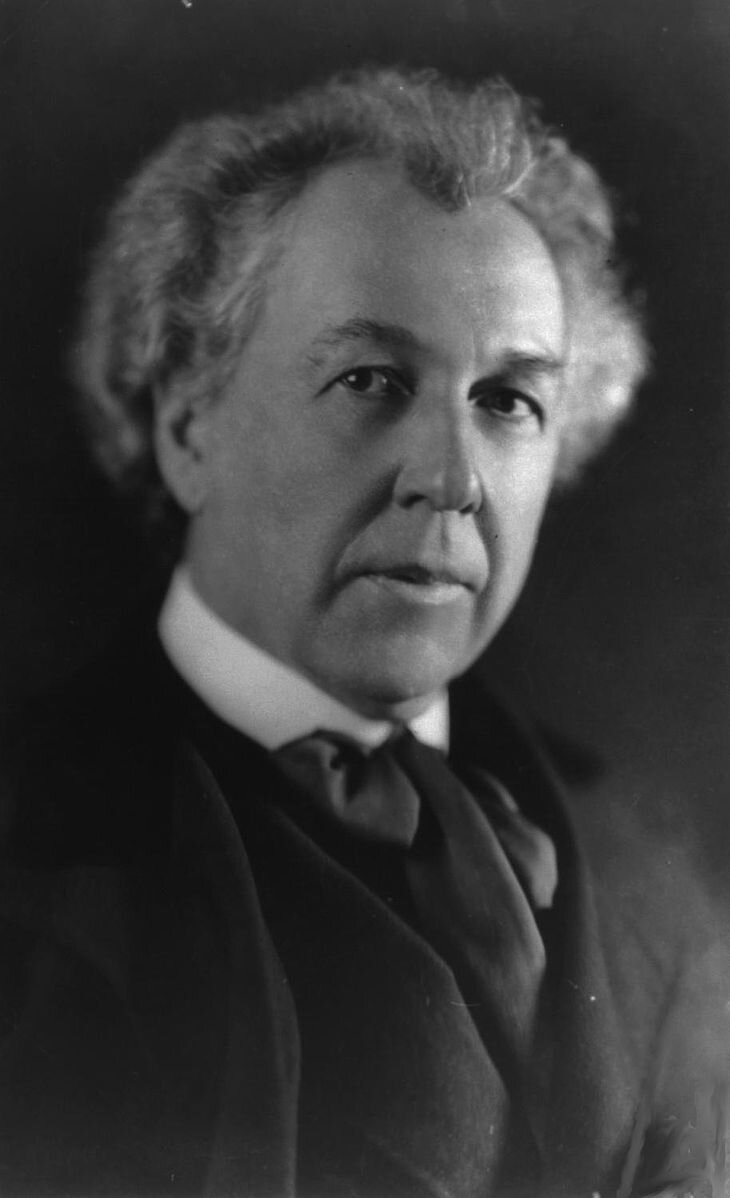

Frank Lloyd Wright

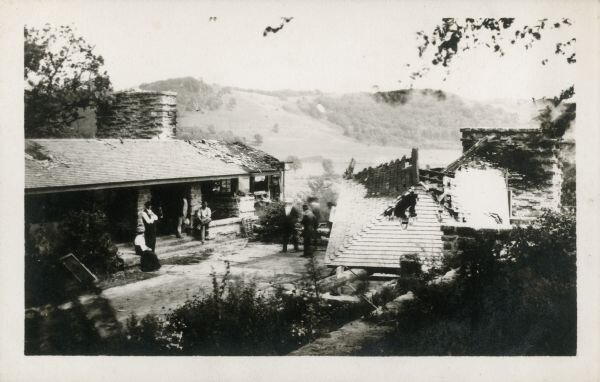

Talisen, Frank Lloyd Wright's Home

Talisen on Fire

Frank Lloyd Wright

Taliesin at a Distance

Mamah Bouton Borthwick

William H. Winslow House Front

Oak Park II Heurtley House

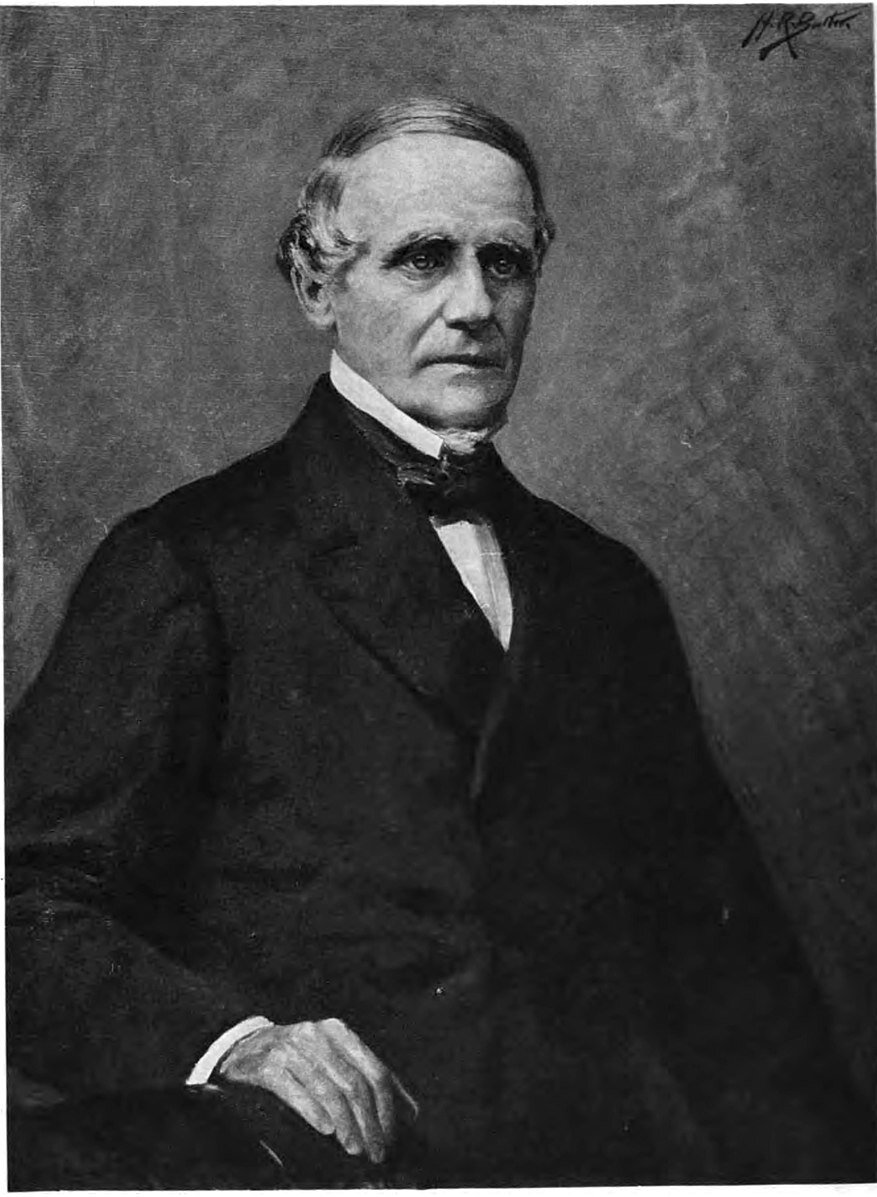

Thomas Kirkbride

LA Hollyhock House Interior

Ennis House

NYC Guggenheim Museum

Griffith Park Train Station

Sources:

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING/MEDIA:

Architect Magazine

History: The Massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright’s love Cottage

Mental Floss: Gifts for True Crime Fans

Washington Post: He Burned Frank Lloyd Wright’s House and Killed his Mistress

Wisn: Motive for Murders at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home Still a Mystery

NY Daily News: Wright Mare Massacre Frank Lloyd Home

Messy Nessy Chic: Murder in the Blueprints of Frank Lloyd Wright

Washington Post: Outlook he Burned Frank Lloyd Wright’s House and Killed his Mistress— But Why?

NY Post: Frank Lloyd Wright was a House Builder and Homewrecker

Architecture Digest: Frank Lloyd Wright Facts

Sfgate: The Secret Curse of Owning a Frank Lloyd Wright

Harpers: Plagued by Fire- The dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Site: John Storer House

LA Times: Best House Photogallery

MUSIC:

Lights Out by The Europa Protoharmonic Symphony Orchestra

Crest and Mantle by Wicked Cinema

What You Do Not Know by Joshua Spacht

IMAGES:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water by Somach on Wikimedia Commons : License

Guggenheim Museum on Wikimedia Commons : License

Winslow House by Oak Park Cycle Club on Flickr : License

Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s home, Spring Green WI by Sports on Flickr : License

Full Script

The Hollywood Hills feel like a whole other world, nested within Los Angeles. Trudging up the narrow canyon road in the hillside neighborhood of Los Feliz (los Fee-lus), you can stand high above L.A., getting some incredible views of its urban skyline. The ocean shines on the horizon. And even with all those polluting cars stuck in traffic down below, the air breathes a little easier up here. On a good day, you can smell a hint of pine.

Los Feliz borders the sprawling Griffith Park – you’ve seen this place countless times on screen, whether it’s the beautiful Observatory appearing in Rebel Without a Cause and La La Land, or the park itself, which posed as the Korean countryside during the legendary T.V. show M*A*S*H. The architecture up here is as eclectic as the people who can afford the houses; but the more traditional homes have a lot of common elements – pan tiled roofs, grand courtyards, pristine swimming pools. Most of the homes are bordered by massive hedges, the better to give the owners a bit of privacy.

Famed architects like Paul Williams and Leland Bryant are behind some of the homes in Los Feliz; and their grand, luxurious designs fit like a perfect puzzle piece into this elegant neighborhood. But there’s one house here that stands out among the rest. It curls around the corner of a winding canyon road just minutes from Griffith Park.

The first time you see it, you might mistake it for a castle at the top of a hill; a mansion made of intricately designed textile blocks stacked in a grand arrangement, the walls cut by 27 dazzling art-glass windows. It’s surrounded by a concrete wall, and a massive iron gate brings to mind a drawbridge from a fairytale palace.

The closer you look, though, those features start to change, revealing something darker. If this is a castle, it is guarded by an ominous force. There is something unsettling about this place, maybe something sinister. As you examine the bewitching, complex patterns of its blocks, you might conclude that this doesn’t look like a castle after all. It looks more like a tomb.

If I asked you to name a famous architect, chances are you would say Frank Lloyd Wright. And there’s a reason why he’s still a household name decades after his death. His designs changed the way we think about architecture; they could be radically innovative while also feeling natural and inviting. Somehow by their very design they made a house feel like a home, more than just a shelter and a place to sleep. He showed just how powerful an impact the elements and organization of a house could have on the people inside it.

His ambitious, prairie-style homes had open concept living rooms and kitchens, welcoming spaces to gather people together. He didn’t need a flattened generic build site or rare and expensive materials. He could build a house over a waterfall. He made slabs of concrete feel unique and beautiful.

And he didn’t just design houses. He designed the world-famous Guggenheim in Manhattan, known for its spiraling, snail-like design. Frank Lloyd Wright said that he hoped to create a museum that was entirely unique, the best of the best, meant to stand out amongst the stretched-out skyscrapers of New York City. And he did.

So why do those works that made Frank Lloyd Wright a household name feel so different from this house in Los Feliz? This place is known as Ennis [eh-nuhs] House, and it’s considered one of the most stunning examples of what architects call the Mayan Revival style, a trend in the 1920’s and 30’s that incorporated design ideas from Meso-American (MAY-SO American) cultures. A survey of experts in 2008 named it one of the top 10 houses ever built in Los Angeles. But in every respect, it feels like the work of a wholly different artist than the Frank Lloyd Wright the world first knew. Instead of open and warm it feels ancient, chilling, and powerfully sad.

And it turns out, if you trace the dark path back through Wright’s life and work, there is a very good reason why he changed his design philosophy so radically; and it raises a haunting question about just how much the places we occupy can affect us. Because when Frank Lloyd Wright built the home he thought represented his ultimate dream, it became the site of a nightmare he could never escape.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 18: Murders in the Wright Houses.

PART ONE

There’s a 19th-century psychiatrist named Thomas Story Kirkbride; his biggest legacy is the design of a radical new kind of hospital for the mentally-ill. Known as “Kirkbride Buildings”, these new institutions were designed to provide soothing and humane treatment. They never quite lived up to his vision, usually because of budget cuts, but they were a drastic improvement over the horrors of previous asylums. Kirkbride had a particular belief – that the architecture itself, with long, well-ventilated corridors and ample natural sunlight, could create a healing atmosphere for patients. The building could be part of the cure.

This is a provocative idea, it’s commonly called environmental determinism and a lot of research in the decades since Kirkbride have given weight to some of his theories. Here at My Dark Path we’re continuing to study Kirkbride and the dozens of asylums built from his proposals – we think there are more stories to tell here, so stay tuned.

But it’s unquestionable that, from the beginning of his career, Frank Lloyd Wright believed in a version of this idea. A home to him was about more than pure function, and even more than an aesthetic pleasure. He believed that he could design buildings that had a powerful, personal impact on the people who entered them. It was his life’s obsession, and his story shows an individual who was not going to let anything stand in his way.

Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8th, 1867 in the quaint midwestern town of Richland Center, Wisconsin. Today, Richland Center’s historic downtown main street looks like a lot of rural Midwestern downtowns – aging and delipidated redbrick buildings lining a single road. In Wright’s time, these buildings would have been bustling with new businesses, with the promise of growth and prosperity.

When Wright’s mother, Anna Lloyd James, became pregnant with her son, she actually imagined that little Frank would grow up to build incredible buildings. Following this intuition, she decorated his nursery with detailed engravings of English cathedrals. While most children were examining pictures of giraffes and elephants in books, Wright could simply glance at his wall and nourish his imagination through the intricate designs of beautiful churches.

Even Wright’s toys foretold his future as an architect. Wright’s mother gifted her son with a Froebel Gifts block set, one of his favorite toys. As a toddler, he was designing buildings of his own with his blocks – learning that he could turn his vivid imagination into something tangible and praiseworthy. In Wright’s autobiography, he credited this block set with shaping his passion for building and design. He writes, “for several years, I sat at the little kindergarten tabletop…and played…with the cube, the sphere, and the triangle – these smooth wooden maple blocks. All are in my fingers to this day.”

When Wright turned three, the family moved from Richland Center, Wisconsin to Weymouth, Massachusetts so his father, a preacher, could minister a small congregation there. They only lasted a few years in the small Massachusetts town, before poor finances sent the family back to Wisconsin. They moved to Madison to be closer to Anna’s family, who helped them with their financial struggles. In Madison, Wright enjoyed a few happy years – he learned music from his father and spent quality time with his encouraging and supportive mother.

Overall, though, Wright’s father was somewhat of a stranger to his son. They shared a love of music, but not much else. And father spent much of his time away from the family. When Frank Lloyd Wright was just 14, his parents divorced. In 1892 this was a much bigger deal than it is today; it wasn’t considered normal in any fashion in the United States. It was an enormous public scandal; and it gave Wright painful memories to associate with marriage and family. Maybe it also made Wright aware of the effect of being in the public spotlight, and made him decide that if he ever became well-known again, it would be on his terms.

After the divorce, Wright never saw his father again. His grief and anguish brought him closer to his mother than ever, as did the experience of being by her side as she endured public humiliation over the divorce. She and her child Frank formed an unbreakable bond that held for the rest of their lives.

This is probably why Frank initially chose to enroll at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, where he could stay close to her. He studied under Allan D. Conover [con-oh-ver], a professor of civil engineering, and while it fed Wright’s love of design and had a long-term impact on his thinking about architecture, he didn’t finish the program. After two years at Madison, he traded the small town for the bustling city life of Chicago, Illinois.

Chicago was still recovering from the Great Fire of 1871 that devastated countless buildings. It was a city in desperate need of architects if they were going to rise from the ashes. Wright was struck by how the cheap construction was more than just filthy and unappealing, it could cost you your life in a disaster. He imagined replacing these burned and tattered ruins with something enduring, safe, and spectacular.

His first job in architecture was at the firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee [silz-bee]; where he worked as a draftsman, making technical drawings. The team there contained several names who would later become famous in architecture – Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher, and George G. Elmsie among them. Wright worked on a church and a school for Silsbee before moving on to an apprentice position at the firm of Adler and Sullivan.

Louis Sullivan (pronounced “Louie”) was one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, he was called the “father of skyscrapers”. His motto was “form follows function”, and this became the core philosophy of modern architecture. He worked closely with his prodigious young apprentice Frank Lloyd Wright – there’s even evidence to suggest that the relationship between the two architects inspired the novelist Ayn Rand in her book The Fountainhead.

Around this time, Wright met his first wife, Catherine “Kitty” Tobin. They were at a church service, and apparently hit it off quickly. They were married just a year after that first meeting. Wright built his own family home in the village of Oak Park. Then he built a second house, next door. For his mother.

By now, his career was booming. He was now the sole architect at Adler and Sullivan responsible for designing residential homes. But still, he felt constrained. Louis Sullivan dictated how the house should look; Wright was not allowed to follow his own instincts and imagination.

Life and success in the big city was feeding his ego. Although he wasn’t wealthy yet, he splurged on luxurious clothing, furniture, and cars. His showy lifestyle quickly plunged his family into debt; and to cover it, he started doing freelance work. He designed at least 10 homes without notifying his employers, many of which still stand in Oak Park. To this day, architecture buffs are drawn to visit Oak Park and the neighboring village of River Forest for having the closest concentration of Frank Lloyd Wright homes of anywhere in the world. Trust me – it’s worth a visit.

But Wright didn’t love these freelance houses, he still thought they were too cookie-cutter. Even though they smoothly blend into the neighborhood around them, in these houses you can start to see the hallmarks of his unique style – open floorplans, horizontal windows; those little elements that added an ephemeral touch of beauty to a functional design.

One day, Louis Sullivan was walking through his neighborhood, and he saw one of these homes. And, just like fingerprints left at a crime scene, the master architect recognized the handiwork of his ambitious apprentice.

Sullivan was furious. Frank Lloyd Wright’s contract forbade him from taking any outside work. But this was more than a professional violation, Sullivan felt personally betrayed. The two argued, and Wright left the firm. In one version of the story, he was fired. Wright always claimed that he walked out and quit.

The truth is impossible to know, but the result was, the brilliant up-and-coming architect was now free to open a practice of his own, where no one would be his boss.

PART TWO

The Winslow House in River Forest, Illinois, is the first home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright with no restrictions and no oversight. He built it in 1893 and 94, but when you look at it, it’s like you can see the 20th century bursting out of the restrictions of the past. Its pleasing geometry makes it instantly recognizable as a Wright house – looking at it from the street, you might as well be looking at a contemporary painting, the contrast between the dark brown brick on top and the orange brick below conveys a soothing balance. This house feels rooted in the Earth in a way that will last. The original owner, William Winslow, had formerly been a client of Adler and Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright had no qualms about poaching customers.

Wright busied himself with work, and left his wife Kitty was in charge of raising their growing family. There were six children, and the first years were seemingly happy ones. Kitty taught kindergarten herself in the family home, with kids from the neighborhood joining them. Wright showered them with arts and crafts supplies to encourage their creative impulses; and of course they got their own Froebel [froh-bl] blocks, the toys that had inspired him so much. He had designed their home to include an expansive playroom, where they could run around to their heart’s content.

Frank and Kitty hosted lavish parties; they had a reputation for a carefree lifestyle, with their children allowed to run amuck among their well-dressed guests. For their social circle, it all worked together with Frank’s reputation as a bold young rebel in his field.

But not everything was ideal for Kitty. First, there was Frank’s mother living right next door. She could be controlling and possessive of her son, and wasn’t shy about exercising the emotional hold she had over him. And there were other women, as well. When Frank wasn’t working long hours, he was flagrantly flirting with and entertaining mistresses. Kitty was handling all the household duties herself, and if her husband’s philandering added to her burden, he didn’t care.

For years he carried on an affair with a woman named Mamah Borthwick Cheney [may-mah bohrth-wick Chae-nee]. They met when he designed a home for Borthwick and her husband. Borthwick was an intellectual, an avid reader who spoke multiple languages – when she met Wright she was translating Swedish literature into English. Wright was dazzled to have a lover he considered to be on his intellectual level; and all but forgot that his own wife and children existed.

The affair of Wright and Borthwick was both heated and highly public. Neighborhood kids once climbed a fence and saw one of their liaisons through an open window. Wright would take Borthwick on drives through town, where neighbors and friends could see them together, carrying on like the lovers they were. Wright was the talk of the town, and he seemed to enjoy it; but it mortified his wife and, gradually, started impacting his business. As gossip and headlines spread about his behavior, he started losing clients – they didn’t want their buildings tainted by being associated with a scandalous name. Eventually, Wright gave up his studio altogether.

But none of this stopped him from carrying on with Mamah Borthwick. In fact, without a studio keeping him in Chicago, in 1909, he and his mistress left the city for Europe, to travel and adventure with no responsibilities. Kitty Wright was devastated, and yet she knew that, for a woman with six children in the early 20th century, being a divorcee would be even worse. Even as her husband and his mistress spent a year together in Italy, Kitty refused to grant him a divorce.

In 1910, Frank Lloyd Wright came back to America. If he tried to reconcile with his wife, it was half-hearted, and quickly abandoned. He purchased land in Spring Green, Wisconsin, with the goal of building a new house specifically for himself and Mamah Borthwick. This project was an all-consuming passion for him; and when it was finished, he gave it a Welsh name in honor of his mother’s heritage – Taliesin (“tal-YES-in”). There was a real-life medieval Welsh poet and bard by the name of Taliesin, who probably lived in the sixth century; but the facts of his life have been colored by myth and legend that describe him as having magical powers. In some legends, he was the bard at the court of King Arthur.

The Taliesin build by Frank Lloyd Wright was a sprawling estate that stretched across 600 acres of land. Some of this land once belonged to the family of Wright’s mother, so reclaiming it had special importance to him. He designed the home in what’s now known as Prairie Style, with gorgeous, wood-framed doors and windows, outcroppings of limestone. He was prouder of it than any other house he ever built.

Society at the time, though, was not so kind. Headlines across the country described Taliesin as a “love nest”, publicly condemning Wright for abandoning his family for another woman. And to everyone’s frustration, he didn’t show any interest in acting contrite in order to restore his career and reputation. He made no apologies.

At this point, his genius was undeniable, and there were enough clients willing to pay any price for one of his creations no matter what society thought of him. Not long after completing Taliesin, he landed an enormous job, designing the Midway Gardens in Chicago.

In August of 1914, he was hard at work in the Windy City, consumed as always by the act of creating new architectural marvels. He had no idea that, when he had last left Taliesin, he had seen his beloved Mamah Borthwick for the last time.

***

Borthwick had two young children of her own, in 1914 they were aged 9 and 12. Her husband was their primary caretaker, but in this particular summer they had come to visit Taliesin for a few months. By all accounts, Frank Lloyd Wright treated them with kindness and patience; lavishing attention on them even while neglecting his own children. Perhaps he enjoyed how much they liked exploring the property he had designed. They took lunches on the porch, breathing the fresh air, being catered to by household staff. It was a summer of luxury and pleasure, all of it made possible by Wright’s architectural achievements.

August 15th was a typically humid Saturday; and the household was bustling. The handyman and cook were a husband and wife, Julian and Gertrude Carlton; and they were tending to the family’s needs while a work crew was engaged in upkeep and maintenance – there was a foreman, a carpenter, and a gardener all at work. The carpenter had brought along his 13-year-old son. It was an energetic atmosphere, but nothing unusual for Taliesin.

In the afternoon, the workers gathered in the dining room for a lunch break. Borthwick and her kids sat around the patio, where Julian Carlton served them their lunch. Julian was originally from Barbados, and he had while he did good work, he had a reputation for being occasionally hot-headed and paranoid. He frequently accused members of the household of “picking on him.” In the weeks leading up to this day, his wife Gertrude saw him becoming more and more irritable and defensive, bordering on paranoid. There’s disagreement over the source of his anger – some say that Julian had put in two weeks’ notice so he and Gertrude could move to Chicago; others that Borthwick had fired him during an argument. In another story, one of the draftsmen had fought with him, used racist insults against him. Whatever the cause, the butler’s anger was becoming uncontainable. To Gertrude’s horror, Julian began to sleep with a hatchet beside his bed.

And so, after serving that Saturday lunch, Julian told his wife to head home, and that he would join her once he finished a few final duties. He announced that he was going to fetch some gasoline to clean the carpet. This was a common technique for removing stains at the time. As he left the room, he locked the doors behind him.

Soon after, one of the workers smelled gasoline, and turned to see a thick liquid seeping into the room from beneath the door. Seconds later, the house was on fire. Chaos ensued. Workers scrambled to free themselves from the flames, but the locked doors trapped them. They ran for the windows, while Mamah Borthwick and her two children dined outside on the porch. Julian Carlton was approaching them, with the hatchet in his hand.

Borthwick barely had time to react before the hatchet plunged into her skull, killing her. Carlton didn’t stop there; he turned his attention to her children. 12-year old John died almost immediately. Carlton hacked at 9-year-old Martha, injuring her head. Amazingly, she managed to run, instinctively heading for the house for safety. But the flames caught her, setting her dress on fire. She passed out, and died on the lawn. Carlton set the bodies on fire, and turned his attention to the workers still in the house.

Inside, many of the workers had also caught on fire. A 19-year-old draftsman named Herbert Fritz shattered a window and threw himself outside, rolling in the grass to extinguish the flames on his body. Carpenter William Weston and gardener David Lindblom also managed to squeeze out of windows, and ran to a neighbor for help.

By the time emergency services arrive, there were bodies everywhere. Four had died directly from Julian Carlton’s attacks, three more died from their injuries in the hours and days that followed, including the carpenter’s 13-year-old son, Ernest Weston. Carlton was found hiding in the basement. He didn’t plan on being taken alive, and swallowed a vial of hydrochloric acid. It failed to kill him; he was taken into custody alive. But his mouth, tongue, and throat were so severely burned that he never spoke again. Seven weeks later, he died of starvation. It’s hard to imagine a grislier, more painful demise for this murderer.

PART THREE

When news reached Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago, he only learned that Taliesin had burned to the ground. He didn’t hear anything about the fate of Mamah Borthwick or the others. He boarded the first available train from Chicago to Wisconsin. He only learned about the brutal murders when a reporter asked him how he was reacting to the news.

Frank Lloyd Wright, who had flown so high, been so blind to the hurt he caused others with his lifestyle, was devastated; grieving and bereft in a way he had never been before. He suffered insomnia, even spells of temporary blindness. At Mamah Borthwick’s funeral, he filled her casket with flowers he had picked himself, straight from her garden. To him, she had been the great love of his life, and he would never stop mourning her until the end of his days.

After several months, he started to rebuild Taliesin; making a second house that was nearly a replica of the first. But for years, as he buried himself in work, he couldn’t live there. He lived at building sites abroad, like when he designed the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan; and when he was in the U.S., he stayed in an apartment in Chicago. Taliesin II, as it was called, served to hold pieces of Asian artwork he was collecting. For years it was more of a museum than a home; perhaps that’s all Wright could see it as.

The house had one more occupant, though. Maybe Frank Lloyd Wright needed a distraction; maybe he just hated to be alone. Or maybe, like with Taliesin II, he believed he had the power to just rebuild the life he had before. But in early 1915, he struck up a correspondence with Miriam Noel, a wealthy divorcee who greatly admired his work and wrote to him expressing her love and sympathy over his loss. They quickly fell into an affair that lasted many years; and he moved her into Taliesin II.

In 1922 Kitty Wright finally granted her husband a divorce. The freedom he had craved for so long was his at last; he married Noel in 1923; and finally moved back to Taliesin II full-time.

The marriage, though, was far from easy. Miriam Noel was more controlling and possessive than his previous partners. Once, she even had him arrested – before their wedding they had traveled together, and it was against the law to transport a woman across state lines for, quote, “immoral purposes”. Despite that she had done so voluntarily, she used it as leverage as their relationship soured. Soon, they were separated.

Before he was even divorced from Noel, he met the woman who would become his third wife. Olga Hinzenberg was 32 years younger than Wright; and, like Mamah Borthwick, was married with children of her own. Before his second divorce was final, their affair accidentally caused a pregnancy; and another round of scandal.

And right around this time, another in the string of tragedies. In April of 1925, Taliesin II caught fire during an intense lightning storm, and burned to the ground just like its predecessor. No one died this time, but his growing art collection went up in flames. A second home, consumed by fire. A second marriage, falling apart faster than the first.

The Wright family motto came from a saying by another Welsh poet: “The Truth Against the World”. Emotionally broken but as defiant as ever, Wright built yet another Taliesin. The effort nearly ruined him. He was already selling nearly everything he had to pay for his second divorce, and to settle the debts from building Taliesin II. The Bank of Wisconsin even foreclosed on the property, before a wealthy former client put together a plan to rescue it. He completed Taliesin III, but made it a school for architects, never again to be a home. Today, it’s a Frank Lloyd Wright Museum.

It was during these years, as he worked to defy and spite all the sources of sadness in his life, that Charles Ennis, owner of a men’s department store, commissioned Wright to build a home for them, in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Los Feliz.

***

It’s easy to imagine the feelings of an artist who would design a home that looks like Ennis House – part fortress, part tomb. For other architects, the Mayan Revival movement was an exciting, decorative style, a way to add flash and character to buildings. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was a way to channel his grief. Fewer and fewer of his works had any of his Prairie School trademarks. Warmth, hospitality, and openness; maybe they just didn’t mean anything to him anymore.

Over the years, Ennis House was eroded by air pollution, rocked by an earthquake, and after a season of torrential rainstorms, was considered so dangerously unstable as to be uninhabitable. Millions of dollars were raised to save and restore it, but it’s no longer open to public visitation. Instead, its one-of-a-kind design has been featured in countless movies and TV shows like Blade Runner, Westworld, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and 1959’s horror classic, House on Haunted Hill. These dark and frightening stories seem to find a natural home around these mournful stones.

Looking back, tragedy and disaster seem unusually attracted to Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings. All the way back in 1902, a grief-stricken widow named Susan Dana hired the young Wright to design her new home in Springfield, Illinois. She had buried two husbands, two children, and a dearly-beloved cousin. A new home represented a chance to start again. But she had never fully-recovered from the losses she suffered; and as her debts mounted during construction, her sanity broke completely. She felt cursed, stalked by death and misfortune. She mortgaged the main house, sold all the furniture, and moved into a small cabin on the property. She hoped to sell the house, but even with the status of a Frank Lloyd Wright house, no one wanted to live in a home where a stranger tormented by mental illness was living in the backyard. Dana eventually was committed to an asylum, and the home finally found an owner in 1944, over four decades after its construction.

Meanwhile, in 1940, Rose Pauson commissioned Wright to build a home for her in Phoenix, Arizona. It was meant to be a vacation home for Rose and her sister, Gertrude. Wright created many famous works across the southwest in his later career, including a winter home for himself in Scottsdale, which he called Taliesin West.

Just one year after the Pausons’ home was complete, though, a single ember blew onto a curtain, and the house burned to the ground. The home’s remains – a stone foundation and a staircase to nowhere – remained untouched for thirty years. It became a derelict site for vandals and neighborhood kids to hang out at; and in 2012, what was left of the staircase simply crumbled, leaving almost no sign left of the Frank Lloyd Wright home that once sat there.

It’s believed that Wright designed or collaborated on somewhere around 400 buildings in his lifetime. Several of them, as we’ve described, experienced some form of disaster. And many, like Ennis House, seem to be monuments to the worst of those disasters - the vicious slaughter of his deepest love and her children.

PART FOUR

There’s one building still in Wright’s birthplace, Richland Center, Wisconsin, that Wright himself designed. The AD German Warehouse, built in 1921, is a redbrick building like many of the others in the center of town – with one notable difference. The top is framed in concrete blocks, with textile designs drawn inside them; similar to the ones I saw at Ennis House. It’s one of his earliest experiments with Mayan Revival – but most of the building is brick; so the intricately designed blocks are an embellishment, not the building in its entirety.

When Wright first started exploring the Mayan Revival movement, part of what drove him was the chance to experiment with concrete. Using concrete in home construction was still relatively new; it was cheap and extremely durable, but not many people believed it could be visually appealing. Wright was fixated on the idea that he could use concrete to create housing that was affordable but still gorgeous and unique. That’s where these textile blocks started – an enduring, beautiful accent that wouldn’t cost much.

But by the time he was building Ennis House, the old bricks were gone. What remained were those blocks alone – mesmerizing and cold, seeming to contain some great power. Or maybe, just some great feeling that couldn’t find any other outlet.

I keep thinking back to that psychiatrist I mentioned – Thomas Story Kirkbride – who believed that a building could have a psychological impact on its occupants. We don’t want to take anything away from the clear guilt and brutal legacy of the killer Julian Carlton, but you can’t help but marvel that Frank Lloyd Wright, who pursued his personal greatness no matter the consequences, saw his life’s work so afflicted by tragedy and misfortune. Maybe it was just bad luck. Maybe he should have just made his buildings more fire resistant. Maybe if you take any random sampling of 100 buildings you’ll find among them someone mentally broken, or some tragic accident, or some great crime.

But I want you to go just a little further with me on this dark path – about one and a quarter miles down the hill from Ennis House, still in Los Feliz, to 5121 Franklin Avenue. It’s another Mayan Revival building, looking like an exotic jungle temple, with a front entrance that resembles a vast, gaping mouth. It’s called John Sowden House, and its designer was not Frank Lloyd Wright, but his son, Lloyd Wright. Lloyd was Frank’s eldest son with his first wife, Kitty, and since 1911 he had been building a remarkable architectural career of his own. Since Frank Lloyd Wright showed little interest in his son growing up, we should credit Kitty for teaching and raising such a successful man.

The son was actually working in L.A. and pioneering Mayan Revival style houses before his father even arrived, and Frank Lloyd Wright hired his son as a construction manager on Ennis House and other projects. John Sowden House, though, was entirely Lloyd’s creation. It pushes the innovations of Ennis House in even wilder directions.

And it has its own home in the annals of criminal infamy. From 1945 to 1950, John Sowden House was owned by Dr. George Hill Hodel, a suspected serial murderer who, for a long time, was the L.A.P.D.’s top suspect in the death of Elizabeth Short, the legendary Black Dahlia killing.

How many ways can the sins of the father pass to the son? Frank Lloyd Wright abandoned his family as surely as his own father had abandoned him. And somehow, both Wright and his son created an architectural masterpiece with a shadow of murder forever attached to it. Should we dig deeper into the mystery of Sowden House, Dr. Hodel, and the Black Dahlia? Drop us a line if you want to walk this dark path further…

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Ashley Whitesides and Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Laura Townsend. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle and our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.