Episode 23: Satan in the Woods, Sinners in Town – Witch Trials Before Salem

The story of Salem has been told and retold many times. So we’re going to tell a different story; because what you probably don’t know is that Salem was not the site of the first witchcraft trial in what would become the United States. Accused witches had been appearing in New England courtrooms for half a century. In many ways, Salem was the last gasp, the most notorious, nightmarish outcome of a process that, maybe, made it inevitable. To understand this, we need to walk further back in time from 1692, down a dark path deep into the New England woods, where strangers coming to a strange continent needed a scapegoat for all the hardships that awaited them, and a face for all their fears.

Listen to Learn More About:

Puritan Culture and History and why Witch Trials became rampant in their culture.

The first "witch execution" in the American Colonies

The women that was convicted of witchcraft three different times

The town in Connecticut that stayed out of the Witch Frenzy

More unique witch trials before Salem's

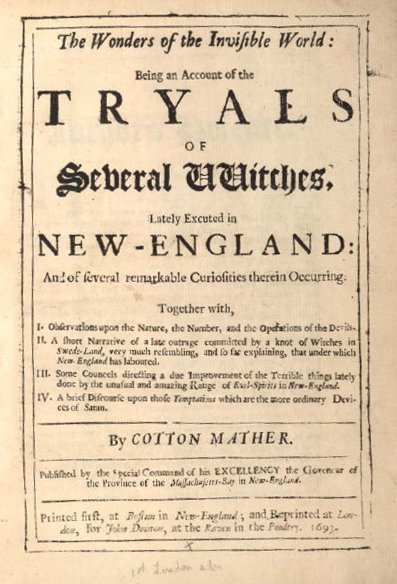

Wonders of the Invisible World-1693

Fall in New England

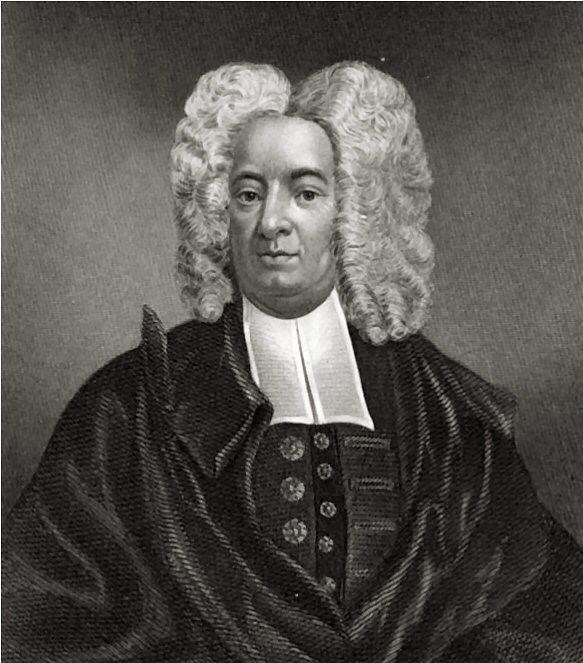

Cotton Mather

Salem aerial view

Salem aerial view

Chocoura Lake in New England

Mary Dyer Being Led

Pilgrims signing the compact on board the Mayflower, Nov 11, 1620, Provincetown Harbor, Mass

Sources:

REFERENCES/ ADDITIONAL RESCOURCES

R.G. Tomlinson, Witchcraft Trials of Connecticut. Hartford, CT: Bond Press, 1978.

Gary Wills, Witches and Jesuits. London: Oxford University Press, 1996.

NPR: “The Real Witches of New Hampshire.”

New York Times: Connecticut Witchcraft Trials

MUSIC:

The Blacksmith by Wicked Cinema

IMAGES:

Salem Aerial view by Doc Searls on Flickr: License

Title page of Memorable provinces relating to witchcrafts and possessions by University of Glasgo Library on Flickr: License

Full Script

I love visiting New England, especially in the fall. Parts of my first visit are fixed firmly in my memory. While I can’t recall which colleges I visited or where my uncle John and I stayed during our drive, my first exposure to the dense forests and rocky shorelines remains a bright memory. The leaves turn the most beautiful colors, the days are warm and the nights are cold, and, as Ray Bradbury says:

“The sky becomes all ash grey and orange at twilight and you can feel Halloween coming in a soft flap of bedsheets and a rustle of broomsticks.”

It’s that last item, the broomstick, that I want to talk about today. Why does the sight of an old broomstick remind us of Halloween? You’ve probably already thought of the answer – it’s witches, who have always been a part of American culture. And the heart of witch culture and legend in the United States is Salem, Massachusetts.

You’ve probably heard the short version of the story – it’s one of a handful of historical events from before the Revolutionary War that every American schoolchild learns. In 1692, a group of teenage girls created a scare throughout their entire community that there were witches among them, hiding in plain sight, spreading disease and curses and sin among the good Christians in town. Over 150 people were arrested, and at least 25 people died, that we know of.

Lives were destroyed, families lost everything, the community was shattered, but the trials continued, and expanded, reaching as far as Boston until cooler heads finally prevailed. In October of 1692 the Governor of the Massachusetts Colony suspended the witch trials, and most of the people still in brutal confinement awaiting trial were quietly released. It was the end of the attempt by the Puritans to create a theocratic government in the colonies – essentially, they had failed the test of being trusted with power. But the damage had been done, and there was no undoing it.

And on a recent trip through the area, I made my way back through Salem to refresh my memory of the area.

Nowadays, Salem has embraced its history and identity as “Witch City.” The town’s official logo is a witch on a broomstick, you can see it on everything from official stationary to the doors of Salem’s police cars. Every year come October the city is flooded by tourists for a month-long celebration of Halloween.

And this horrific incident over 300 years ago continues to ripple through popular culture. In school you may have read or seen Arthur Miller’s legendary play The Crucible, which saw parallels between the Salem Witch Trials and the “red scare” of America in the 1950’s, when people lost their careers if they were suspected of associating with Communists. There are even parallels to today’s cancel culture where those who don’t toe the popular culture’s orthodoxy are singled out for destruction. The very term “witch hunt” has come to refer to a paranoid search for crimes and criminals that do not, in fact, exist.

TV shows and movies regularly use Salem as a backdrop for their own stories of witchcraft; whether it’s the TV series Sabrina the Teenage Witch, the hit horror film The Conjuring, or this year’s hit Marvel show WandaVision, witchcraft is linked to Salem and those colonial years in America.

But here’s the problem with this, and with the town of Salem turning their dark history into a logo – there were no witches in Salem. And there never were. If we turn history on its head, if we give in to the fun of a spooky story and indulge in the idea that it might be real, then we turn the horror of the witch trials on its head. Twenty-five deaths happened because of nothing but human fear and hatred. Nineteen women were hanged in Salem. Five more died in inhumane conditions in jail. And then there was Giles Corey, who refused to make false accusations to protect himself and was literally pressed to death by stones. The story goes that his last words were: “More weight”.

People did this; and they did it to other people. In a way, that’s even more horrifying; and perhaps the darkest detail of this – it was all legal. There were accusations, trials, legal arguments, presentations of evidence, and a death sentence backed by the moral authority of the state. Nobody in Salem saw themselves as part of a lynch mob; everything happened in plain sight. Later, one of the judges apologized for his role in the trials, and asked forgiveness from the families of those executed. I doubt that it brought much comfort.

The story of Salem has been told and retold many times. So we’re going to tell a different story; because what you probably don’t know is that Salem was not the site of the first witchcraft trial in what would become the United States. Accused witches had been appearing in New England courtrooms for half a century. In many ways, Salem was the last gasp, the most notorious, nightmarish outcome of a process that, maybe, made it inevitable. To understand this, we need to walk further back in time from 1692, down a dark path deep into the New England woods, where strangers coming to a strange continent needed a scapegoat for all the hardships that awaited them, and a face for all their fears.

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 23: Satan in the Woods, Sinners in Town – Witchcraft Trials Before Salem.

PART ONE

The key to unlocking the history of witchcraft trials in New England is a single word – Puritans. What you know about Puritans is going to differ drastically depending on where you went to school. In America, when we learn about these early colonists, or tell the legend of Thanksgiving, you get a pretty anodyne picture – that the Puritans, or the Pilgrims (which is what Massachusetts Puritans called themselves,) were simply devout Christians who had been persecuted in England and came to the New World for freedom, so they could worship God as they pleased. That they befriended the local Native Americans and worked together to survive the harsh winters and set a bounteous table together.

Very little of that is actually true. Tell this story to someone who went to school in England, and they might look at you in horror. Because here’s the story of Puritans in England: They were vocal extremists, united in their belief that the Church of England was sinful and corrupt and needed to be purified in the name of God. They had gained serious influence in the country, King James I ordered the creation of the King James Bible, one of the most influential translations of the Bible in history, in part to appease the Puritans.

Some of them indeed set sail for America, in order to escape a country they thought couldn’t be redeemed. But many other Puritans stayed behind, and when Civil War broke out over the power of the King and the dominance of the Church of England, the Puritans were on the side that executed King Charles the First, and helped form their own repressive, religious government led by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. You see, their belief that they should be allowed freedom to worship as they pleased didn’t extend to anyone else being free to worship as they pleased. That’s what the British think about when they hear the word “Puritan”.

But let’s look at the ones who left before that Civil War, the ones who dreamed of building God’s Kingdom in the American colonies. In their minds, since everyone in their communities were committed Puritans, they would be able to build a perfect society, free of sin, free of the influence of Satan. And, in their belief, the surest sign that Satan was at work in your community, was a witch.

The Puritans weren’t the first to fear witches in their midst. The Catholic Church and early Protestants all had witch trials of their own. When Joan of Arc was burned at the stake, it was because of the belief that Satan was working through her.

The problem with witches is that it is very difficult to tell who, among your friends and neighbors, actually is a witch. They didn’t have the popular image we have now, dressed all in black, with a pointy hat and green skin. You can blame the movie The Wizard of Oz for that. Technicolor was new and spectacular in movies at the time, and the filmmakers were looking for every opportunity to show it off – the brilliant yellow brick road, the ruby red slippers; and, to top it off, green makeup for actress Margaret Hamilton to play the Wicked Witch of the West.

But for the Puritans, a witch looks just like anybody else. It could be your neighbor who you never liked for reasons you can’t put your finger on. It could be the old woman who was rude to you last week. And they weren’t harmless tricksters casting little spells and taking in black cats. In the minds of these colonists, witches were the earthly agents of Satan, on a relentless mission to destroy society, and corrupt and torture decent Christians. If you’re old enough to remember the intense fear that could be conjured by the word “terrorist” after the 9/11 attacks, that is probably a good approximation for what a Puritan felt when you said the word “witch”.

Think about what it would have been like to see a production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth in a time like this – witches right in front of you on stage, mixing potions, summoning bloody and strange visions, and speaking dark prophecies that come true every time, but never how you expect.

Witches were a threat in the old England that the Puritans left behind. There were even witchfinders who claimed to hunt down and execute these witches. Now, living without the resources of England, in primitive communities, surrounded by Native Americans with their own religious traditions and practices, Puritans felt isolated, confused, and vulnerable. But they were determined to show how righteous they were. So they were going to fight witchcraft under the auspices of the law. It was the duty of every citizen in a Puritan colony to be vigilant for signs of witchcraft; and make sure the authorities were notified.

They believed that Satan would target the weakest people in the community – and a Puritan believed that women were inherently weak and susceptible to temptation. A witch didn’t have to be a woman, but in their minds, a woman was naturally most likely to be turned to witchcraft.

To really paint the picture of life in these communities, you have to let go of your image of a town or city – all the history which happened at this time happened among very small populations. In 1692 when Salem erupted, Boston was the largest settlement in Massachusetts, but its population was just 7,000 people. Salem was home to only 550 people, living in 90 houses, surrounded by miles of heavy forests, wildlife, and Native American tribes.

Just 550 people – that’s smaller than some suburban neighborhoods. And the death toll from the Witch Trials was 25, almost 5% of their population. So you have to picture people living deep in isolation, surrounded by the unknown, and with a strong set of prejudices. One of the best movies that depicts the isolation of this time, I’d recommend you watch the movie, appropriately titled, the Witch from 2015.

Many of us grow up with fairy tales that warn about the dangers of going in the woods alone; but for a colonist in New England, the woods, they genuinely believed, were where every danger lurked; including Satan himself. For many of the accused people we’re telling you about today, one of the charges brought against them was that they spent time in the woods.

And before any of us listening today stands up and condemns the ignorance of the past, believing that we are too modern, too sophisticated to do the same... I’d simply ask that when we see faults in others, that we examine our own lives first. Motes and beams are not just an artifact of the past.

We’ll start 45 years before Salem, in 1647, in the colony of Windsor, Connecticut. An epidemic of influenza swept through the community; killing ten women, nine men, and nine children. It was devastating; and the town, grieving and angry, needed someone to blame. Remember, at this point, nobody really knew what caused a disease to spread – the germ theory that is now foundational to modern medicine was just a fringe idea, not yet fully developed.

The Puritans saw themselves as God’s most favored servants; and, as a consequence, they believed that Satan was on a mission to destroy them. If crops failed, it wasn’t the climate or their farming techniques – it was Satan. So this awful plague that stole so many lives had to be the work of a witch.

Sadly, we have nothing in the historical record to tell us who Alse Young was. Nor do we know what caused her neighbors in Windsor to believe she was in league with the Devil. Her only surviving appearance in history is a notation that on May 26, 1647, Alse Young of Windsor, Connecticut, was executed for the crime of witchcraft. The first such execution in the American colonies, that we know of.

Before Salem, Connecticut was the most notorious site for witchcraft trials. And again, we’re talking about such tiny populations. Hartford had just 700 citizens, Windsor and Middletown were even smaller. Everybody knew everybody; so these accusations were always deeply personal, and the fallout was felt by everyone in town.

A year after the state-sanctioned execution of Alse Young, Connecticut Goodwife Katherine Palmer was accused of being a witch. But her trial ended quite differently – it was dismissed; and she was set free with a warning not to provoke suspicion in the community again.

When I said earlier that the Puritans believed that this whole process was moral and legal because they held a trial, I meant it. In the frenzy of Salem, the fear and paranoia dismantled all the procedures that tried to make these trials fair, but before Salem, the outcomes were not necessarily pre-determined; your fate could vary widely depending on where the trial was held, and what evidence was submitted against you. In a true justice system, of course, no one would have been put on trial for witchcraft at all, but this is what we had in the Colonies.

In 1648, the same year Goody Palmer was released with a warning, Mary Johnson was tried and found guilty of “familiarity with the devil.” She had previously been convicted of theft, and whipped in the town square; but for consorting with the devil, the punishment was death. Cotton Mather, the famous Puritan minister who would later become involved in the Salem Witch Trials, wrote about the hanging of Mary Johnson in his book, Memorable Providences. Quote: “At her execution…she went out of the world with many hopes of mercy…and she died in the frame of mind extremely to the satisfaction of them that were the spectators of it. Our God is a great forgiver.” End quote.

In other words, the Puritans who gathered to watch her execution approved of how Mary Johnson comported herself before her death. They agreed that she absolutely deserved to die, but generously allowed themselves to hope God would forgive her because she let herself be hung in such a dignified way.

In 1651, a married couple, Joan and John Carrington, were found guilty of the same crime. Remember – a witch didn’t have to be a woman. And as they supposedly practiced witchcraft together; the Carringtons were hung together.

PART TWO

Now not every accusation ended in execution, or even conviction. An accusation of witchcraft was a serious business, and if you accused someone without adequate cause, there could be real consequences. In one case, Mary Staples – funny enough, the great, great, great, great, great, great grandmother of Winston Churchill – was accused of being a witch and a liar by her neighbor Robert Ludlow in 1654.

But the court ruled that Ludlow had no justification to suspect Staples of being a witch. He was found guilty of defaming her, and the court ordered him to pay ten pounds in restitution and five pounds to cover court costs. That’s about two thousand dollars in today’s money. That ten pounds, by the way, didn’t go to Mary Staples – legally, it was awarded to her husband.

From 1655 to 1661 Connecticut saw what historian R. G. Tomlinson calls “the period of acquittals.” Accusations of witchcraft were still made, but those few cases that made it to trial were usually dismissed. Elizabeth Goodman was an elderly woman living in New Haven who, according to the record, began acting strangely in public – talking to herself, scolding her neighbors, making bizarre and fanciful claims.

Today we might reasonably examine whether these were early signs of dementia or some other age-related condition; but Puritans had no knowledge of such things. She was put on trial for witchcraft in 1655. The court ruled that the grounds for suspicion were obvious and strong; but that the evidence was not compelling enough to convict her. She was told she could be released on her own recognizance if she could put up a bond of fifty pounds – roughly $7,000.

The worst panic over witches in Connecticut happened in Hartford from 1662 to ’63, thirty years before Salem. There was dissension in the community over the authority of the local pastors; and a number of households, who referred to themselves as “the withdrawers”, left the town and moved north, to Massachusetts. After this schism, which sent anger and tension throughout the community, 8-year old Elizabeth Kelly claimed she had been bewitched by her neighbor, Goody Ayres. Little Elizabeth grew more and more ill until one night, finally, after her father promised to go to the authorities, she cried out, “Goody Ayres chokes me!”, and then died.

As her body lay in the casket, her parents showed the authorities the bruises on her neck, where Goody Ayers allegedly choked her. There was an autopsy at the graveside, and the authorities questioned Goodwife Ayers and her husband, William. The Ayerses then accused others of using witchcraft to frame them. These accusations and counter-accusations escalated, but Goody Ayers and William, perhaps realizing there was no good outcome in this for them, fled Hartford, leaving behind not only all their possessions, but their eight-year-old son.

Their escape only made them appear more guilty, and the town began to panic that witches were loose among them. A twelve-man grand jury was empaneled

to find those in Hartford who had “familiarity with the devil.” They indicted Mary and Andrew Sanford, but only Mary was found guilty. She was hanged in 1663.

Meanwhile, three local women had strange fits, and assumed they had been bewitched. It may seem silly to us, but in the Puritan world it was an explanation that covered just about any unknown event; the same way the Ancient Greeks might blame a storm over the ocean on the God Poseidon.

Elizabeth Seager was accused of flying over the town. Three other people accused at the same time as her were convicted and executed; but, amazingly, Elizabeth was acquitted. In court, a man named Robert Stearn testified, “I saw this woman, Goodwife Seager, in the woods with three women and with them I saw two black creatures like Indians but taller.” He then stated he saw her fly.

When they acquitted her, the jury explained that while her presence in the woods with devilish creatures would be highly disturbing, they simply had not seen any compelling evidence that she flew; and, based on that, they dismissed the rest of Stearn’s testimony. In Salem, the accusation probably would have been enough to send her to her death. But in Hartford, Elizabeth Seager survived.

But then, in 1665, she was accused of witchcraft again by her neighbors. And this time, she was convicted, and sentenced to hang. She only survived because of the intervention of the colony Governor, John Winthrop, Jr. He disagreed with the sentence, called a special court, and had the sentence vacated and the charges dismissed.

There were more executions after this, but the regular trials were producing an unbearable level of acrimony in the community; and frequently accusations were blowing back on the accusers, who were forced to pay restitution if they lost their case. The pendulum appeared to be swinging back from irrational fear towards a more humane caution and doubt.

Of course, Connecticut and Massachusetts were not the only colonies to see trials – there are more stories to tell in Maine and New Hampshire, including the incredibly unusual story of Eunice Cole.

Eunice and her husband William arrived in New England in the 1630s, in debt as many immigrants are. They settled in Hampton, New Hampshire, where Eunice quickly developed a reputation as an argumentative woman. If you were her neighbor, you were likely to wind up in heated disputes about property lines, livestock roaming, even just looking at her funny. In 1645, she was sued for slander. In 1647, both she and her husband were charged with stealing a pig. There was an additional charge to come out of this incident – when a constable came to arrest her, Eunice was accused of biting him.

To the Puritans of New Hampshire, such a disagreeable person was clearly in league with the Devil. Neighbors began to gossip that she was cursing them, causing their livestock and children to fall ill. She was accused of causing ships coming from England to sink. Nothing was beyond the capricious and insidious magic of Eunice Cole.

Finally, despite the risk of losing in court, her neighbors formally accused her of witchcraft. But once these accusations were brought to light, the evidence was, let’s say, a little thin. Her accusers claimed that, while they were discussing the possibility that Eunice had bewitched and killed a local child, an invisible cat came and scratched at their windows. Definitely not the wind – a magic, invisible cat.

They also claimed that they’d spied a witch’s mark on her body. She didn’t routinely show off her body in public, they said it was revealed while she was being publicly flogged for a different crime. When the court invited the neighbors to locate the mark on her body, they claimed she had scratched it off.

This was apparently too flimsy even for a Puritan court to sentence someone to death. Nevertheless, she was found guilty of witchcraft and sent to prison. While she served her sentence, her husband William passed away. She returned to Hampton with no husband and no property. She lived in a small hut on the town green, dependent on the kindness and charity of the same neighbors who had tried to have her executed.

Incredibly, this happened to her two more times. Eunice Cole was put on trial for witchcraft a second time in 1673, was found guilty, but without sufficient evidence for a death sentence. And then the whole process repeated itself in 1680.

After that, Eunice Cole vanishes from the historical record. We don’t know when she died or where she is buried. Like poor Alse Young, most of what we know about her comes from the trial records. Yet, unlike Alse, Eunice Cole was put on trial for witchcraft three times; and each time walked away with her life. I can’t imagine the fortitude and spirit it took her to endure an experience that was simultaneously so harrowing and so absurd.

But if you want to take about spirit, consider Jane Walford, another three-time victim of witchcraft accusation. Her first experience came in 1648, when she was accused by her neighbor, Elizabeth Rowe. Not only was Jane found not guilty, she turned around and sued Elizabeth Rowe. She won this suit, and Rowe was ordered to pay a sum of two pounds and make a public apology. I’m betting the apology hurt worse.

In 1656, another of Jane Walford’s neighbors, Susanna Trimmings, levied another accusation of witchcraft. Susanna claimed she saw Jane in the woods late at night; that Jane attacked her with a clap of fire, then transformed into a cat and ran away. But these more ridiculous stories aside, seeing Jane in the woods was serious enough. The woods were, after all, the Devil’s domain.

Susanna’s cunning plan to get her neighbor executed failed however – Jane had a witness for the night in question. She wasn’t in the woods, she was home with her husband; and other neighbors had seen them there. Once again, she was found not guilty.

Finally, a few years later, a physician from Boston presented Jane Wilford with her third accusation of witchcraft. And, for a third time, she was found not guilty. She sued the physician and, once again, was victorious. He had to pay her five pounds and, just like Elizabeth Rowe, publicly apologize to the woman he had falsely accused. And if anyone dared suspect Jane Wilford of being in league with Satan after that, they certainly didn’t press charges.

PART THREE

Right around the time Salem was beginning its descent into fatal madness, another set of witch trials was unfolding in Stamford, Connecticut. You probably haven’t heard of them, they were much smaller, and had a much different result. The people of Stamford had heard news of what was happening in Salem; and, rather than give in to the same fear, they were determined that it wouldn’t happen in Connecticut.

All the other parallels were there. Stamford was a Puritan settlement, just like Salem. Their population was just 500 souls, give or take, very similar in size. Everybody knew everybody, not everybody got along, and there was a bone-deep belief that Satan was conspiring against them and witches were real. But the two towns went down different paths; and it’s worth it to study the differences.

In April of 1692, a disturbance broke out in the house of Daniel and Abigail Wescott. They employed a serving girl, one Katharine Branch, and she refused to work because, she claimed, she was bewitched. When Abigail went to rouse the girl from bed, Katharine cried out, “A witch! A witch! Why will you kill me? Why will you torment me?”

Now, to her credit, Abigail Wescott didn’t immediately assume there was a witch and run to find a constable. Her first instinct was that a seventeen-year-old young woman was being lazy and did not want to do work. She wanted to beat the girl until she stopped pretending, but her performance was undeniably disturbing; so Daniel Wescott encouraged his wife to take a wait-and-see approach.

Eventually they summoned the local magistrate, but even he could not tell if the girl was genuinely bewitched or faking it. The Reverend John Bishop was then invited to get involved. Bishop was a big deal in the area. He had graduated from Oxford in 1632 and had served as the pastor of the Puritan church in Stamford for five decades. He personally observed Katherine in the throes of her torment, then returned to visit the Wescotts with Reverend Thomas Hanford, the Puritan pastor of nearby Norwalk. The two clergymen agreed in their assessment – the girl was not faking, she had been bewitched.

This jarred the whole community; because a witch is a threat to everyone. Neighbors started to work in shifts, keeping Katherine comfortable in her suffering while watching and listening for any clue as to the identity of the secret witch who lurked among them.

Eventually, Katherine escalated the situation – she claimed that the devil was at her window, and had brought three witches with him. And she called them by name – Elizabeth Clawson, Goody Miller, and Mercy Disborough. The Wescotts had a long history of disputes with Elizabeth Clawson over some bartering deals; and Mercy Disborough was widely-disliked in town. No one recognized the mysterious “Goody Miller”, but two names were enough. Clawson and Disborough were now at the mercy of the judicial system.

A preliminary court of inquiry was held on May 27, 1692. Four local magistrates were asked to start the investigation. Even in colonial times, trials were costly, time-consuming things, so a preliminary court served to identify whether enough substantial evidence existed for a full trial.

In addition, everyone knew the story of the Hartford witch panic from thirty years before; the one that led to the hanging of Mary Sanford and the acquittal of Elizabeth Seager. But while for some, it was a story that reinforced the real threat of witches – for others, the real lesson was the danger of making rash accusations without evidence.

The preliminary court in Stamford wanted to make sure they got it right; especially given the horrible news still coming out of Salem. The court made a very important decision that seems ridiculous in retrospect, but is probably the key reason why things didn’t turn out like they did in Salem. The court in Stamford refused to allow the introduction of what they described as “spectral evidence”. Young Katherine claimed that the witch Elizabeth Clawson took the form of a cat and scratched her. This claim was not entered in court. In addition, the judge felt it was necessary to take into account the relationship between the accused and the witness; allowing for the idea that there might be bad faith in the testimony of the accuser. Again, this seems so obvious in retrospect; but it certainly wasn’t being considered in Salem.

Although the community had a good deal of hostility towards Clawson and Disborough, they still were not convinced Katherine was telling the truth. Even Abigail Wescott still doubted her servant, and asked the local midwife to “bleed her” in order to ensure it was not a physical ailment or trickery causing her fits. They learned nothing conclusive.

The court interrogated the two accused witches, and then determined to test them through a procedure called “ducking”. You’ve probably heard about this exercise in quack logic – the idea was that, since water is used in baptism for Christians; if a person who wasn’t a proper Christian were submerged in water, the water would reject them and push them up to the surface. This would somehow prove that they were a witch. And if they sank into the water, it meant they were a good Christian, although in very immediate danger of drowning.

So Elizabeth Clawson and Mercy Disborough got their arms and legs tied together and were thrown into a body of water. They both floated. But, fortunately for them, the court ruled that the test was inconclusive, since, in the words of a famous Puritan, “not all water is the water of baptism”. The two accused witches probably wished the court had made up its mind about that before throwing them in.

The investigation was thorough, and spread out over months. It was such big news throughout Connecticut that the Deputy Governor was giving his opinion on what constituted acceptable evidence.

The trial finally began on September 14, 1692, right around the same time two men and seven women were being sentenced to hang in Salem. It didn’t take long – on October 28th, Mercy Disborough was found guilty of familiarity with the devil and witchcraft, and Elizabeth Clawson was acquitted.

The judge seems to have been caught off-guard by the split decision. Was the evidence against one woman really that much more compelling, or did the jury just have a special animus towards the unpopular Mercy Disborough? The judge sent the verdict back to the jury to re-consider. They came back and insisted that she was guilty.

Mercy appealed, and the verdict was elevated all the way up the Governor. In the end, he decided to pardon her. Stamford’s own taste of witch mania was over – and nobody had been executed.

PART FOUR

What is the purpose of the law to you? Is it a tool to punish the guilty, or a system to protect the rights of the innocent from paranoia and vigilantism? Is it worse to see someone innocent punished or someone guilty go free? These questions were at the heart of America’s founding, several of the amendments in the Bill of Rights added to our Constitution address this directly; but even today, we struggle with these uncomfortable questions; don’t we? It’s not always easy to say innocent until proven guilty, but it’s a principle that goes right to the heart of what kind of society we make for ourselves. Because, sooner or later, lives are on the line.

And I think it’s the key question in understanding why Salem became such a horrific outlier in the story of witchcraft trials. The trials themselves were a regular occurrence throughout New England for years; regular enough that not one, but two women could find themselves accused on three separate occasions.

Remember when I mentioned that the Stamford trials didn’t allow the introduction of “spectral evidence”. Well, the courts in Salem did; and when a witness claims that your spirit came to them in the night and pinched them, how can you prove them wrong?

Funny enough, the last witchcraft trial in Salem, and in the United States as a whole, happened almost two centuries later, in 1878. A Christian Scientist named Lucretia L.S. Brown accused a fellow Christian Scientist named Daniel H. Spofford of bewitching her through “mesmerism” – an early version of what we now know as hypnosis. The judge tossed out the case quickly. The law, it seemed, was no longer inclined to entertain such outlandish charges.

We can look down on the superstitions of the Puritans, their belief in the reality of witchcraft and Satanic magic; but in Connecticut, even when they believed they had a witch in custody, they followed a procedure that actually does resemble some modern law enforcement practices.

First, a determination had to be made if what happened was indeed witchcraft. Bad luck and unfortunate coincidences are not always the work of the devil. Second, the individual that performed the alleged witchcraft had to be correctly identified by interviewing all witnesses. Third, all available evidence, both for the charges and against them, had to be gathered. And the findings of the evidence had to be corroborated by at least two sources. Finally, all the gathered evidence and witnesses were presented at a trial conducted under English Common Law.

This was why so many of these trials before Salem ended before acquittals. Often, the Puritans genuinely believed there was a witch. But many of these colonial communities also saw that there could be terrible consequences to abandoning a system of justice. These accused witches that their lives were on the line as a new society put the integrity of its justice system to the test; but you find examples in this in almost every story of colonization and frontier settlements.

Salem has set the standard for what we think colonial witch trials were and how they are depicted in popular culture; but in a way they were the exception, not the rule. We can’t feel good about the idea of witch trials happening at all; but in many cases, the system, in its own rudimentary and superstitious form, protected the innocent.

In the spirit of Halloween, let’s acknowledge that the New England colonies must have been a terrifying place to live after leaving behind the relative comfort and civilization of England. But it’s okay to be scared of the woods without the devil literally lurking within them. Maybe that’s why we collectively indulge in an annual celebration of the fears and superstitions we all carry; just to remind one another that it’s alright.

But it’s that collective choice we make – about justice, about the purpose of the law and the process of proving guilt - that decides whether or not our fears lead to a Stamford witch trial or a Salem one. Laws and customs are only useful if we invest, follow, and defend them. If we exercise them with favoritism, or discard them because we do not care for the status quo, there is no telling how much damage can be done to the community, some of it irreparable.

The law and those Puritans who were willing to follow it, even if they did not care for the results, saved innocent lives and prevented tragedies, whereas a willingness to believe the worst of others without evidence, that one’s enemies are in league with dark forces and thus do not deserve the protection of the law, led to injustice, unrest, and the deaths of many innocents. The Puritans in Salem tolerated no dissent, were willing to smash through any law or custom that stood in their way, and believed that any act of violence they committed was justified, since they were so convinced that they acted in the name of God.

There’s a line in Robert Bolt’s wonderful play A Man for All Seasons, which tells the story of Sir Thomas More and his execution for refusing to endorse King Henry VIII’s break from the Catholic Church. With his life in the balance, More describes the law as a great forest planted by the people of the country, and asks his accusers if they would be willing to cut down that forest to catch the Devil. They answer that they would cut down every law in England if necessary, and then he says:

“And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned around on you – where would you hide, the laws all being flat?...Yes, I’d give the Devil the benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake.”

It’s true that, in strange land, the wild woods can seem like a dark path; but what we do with that fear isn’t the fault of any witch or devil, it’s up to us. Happy Halloween.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Kevin Wetmore, whose voice you also got to hear. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle and our fact-checker is Nicholas Abraham; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.