Episode 16: The Forgotten Games of the Modern Olympics

Listen to Learn More About:

Forgotten Sporting events like rope climbing, tug of war, croquet, and angling

Forgotten Olympic art competitions like architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture

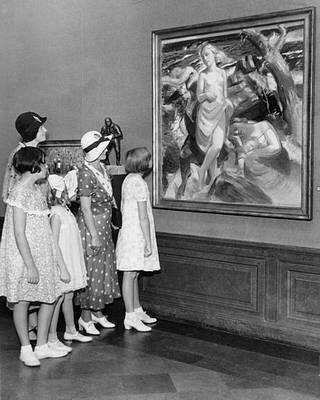

Father of the modern Olympics Pierre de Coubertin

Successful amateur Olympic competitor Spyridon Louis

At the first modern Olympics in Athens in 1896, anyone who showed up on the day of competition would have an opportunity to compete.

And as for what events they would compete in? The classical Olympics were more than sporting events: they included poetry readings, debates, art, theatre, diplomatic meetings between sworn enemies. And Pierre de Coubertin wanted all of this in the modern Games.

This created an argument which, in some respects, carries on today: What constitutes an official Olympic Event? And that’s what we’re exploring in this first of two Olympic episodes on My Dark Path. These are the unusual, the forgotten and the absurd events run at the modern Games. Let’s see how deep we can dive – by the way, seeing how deep you could dive was one of the events…

IMAGE GALLERY

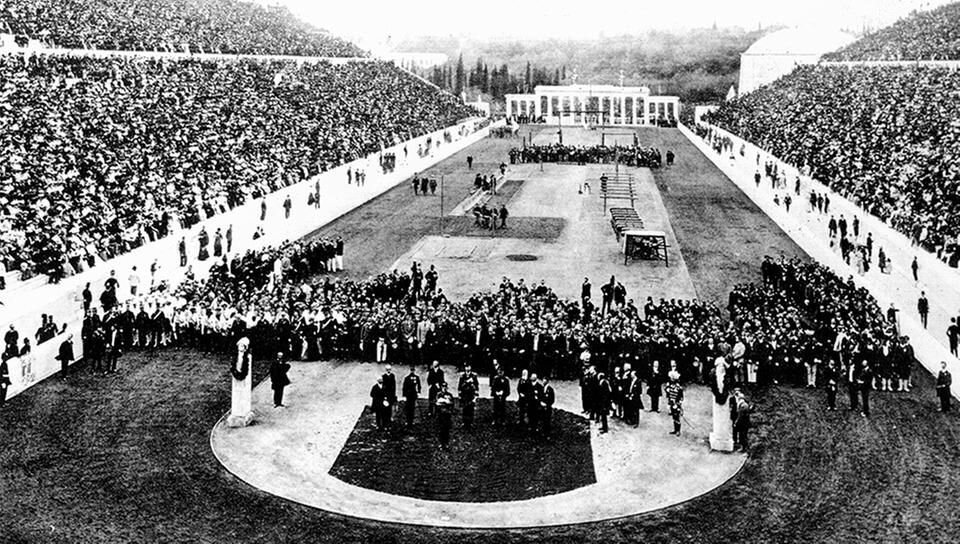

Photo from the first modern olympics

Runner up pistol shooting at the 1908 olympics

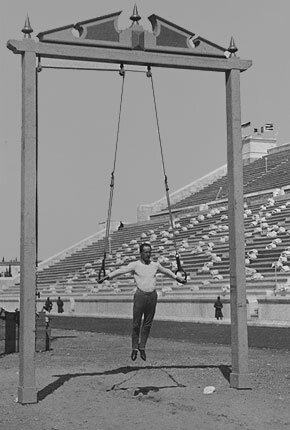

Olympic Art Competitions in Painting 1932

Parade of the winners of the 1896 Summer Olympics

Olympic swimming_1896

Pierre de Coubertin

London 1908 Shooting Competition

Olympic Rings

Louis entering Kallimarmaron at the 1896 Athens Olympics

Croquet 1900 Summer Olympics

Baron Pierre de Coubertin

Annette Kellerman 1907

Annette Kellerman in Venus of the South Seas Poster

1900 Olympic Angling

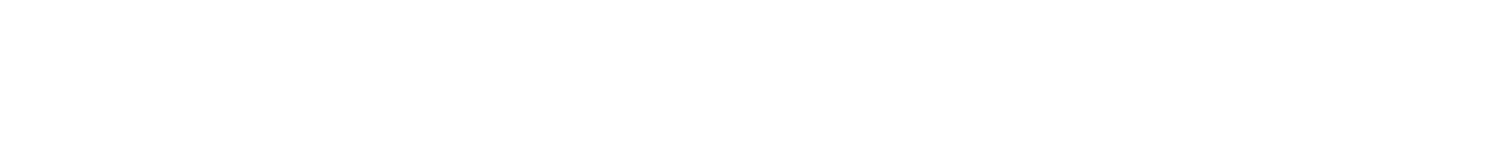

1896 Summer Olympics Rope Climbing

1896 Olympic Opening Ceremony

Sources:

READINGS AND ADDITIONAL REFERENCES:

“9 Really Strange Sports That Are No Longer In The Olympics” (TIME)

“Going For The Gold” When Town Planning Was An Olympic Competition”

“Live Pigeon Shooting and Other Odd Olympic Games” (NPR)

“Live Pigeon Shootng” (Top End Sports)

“Pigeon Racing in 1900” (Top End Sports)

“Plunge for Distance” (Wikipedia)

While this is indeed a Wiki article, the sources it provides are fascinating. It’s a very good place to start.

“Rope Climbing At the Olympic Game” (Top End Sports)

“The 10 Strangest Olympic Sports” (CNN)

“Thirteen Ridiculous Sports that Used To Be Part of the Olympic Games”

(24/7 Wallstreet; reblogged by Business Insider)

“Weird and Forgotten Olympic Sports” (How They Play)

MUSIC:

Stuck in Reverse by Bryant Lowry

I Will Deliver by Strength to Last

Derming of Unity by Cody Martin

Perfect spades by Third age, Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES:

All images on this page are free of copyright restrictions

Full Script:

Tokyo, Barcelona, Sydney – some of the greatest cities in the world. Each with a rich history, and a distinct culture and flavor that shows off the true breadth of diversity in the human race. And each of these cities and dozens share a common element that changed them – they each played host to the Olympic Games.

The Olympics are kicking off in Tokyo, one year late; and we here at My Dark Path are thrilled. I’ve personally visited multiple Olympic cities, and the footprint you can see left behind by the great facilities, the historical accomplishments, lets you step into some legendary stories. So we’re devoting this episode and our next episode to walking some of the more overlooked paths in the history of the Olympic Games. Trust me when I say that as soon as we opened up this topic for exploration, what we found was incredible.

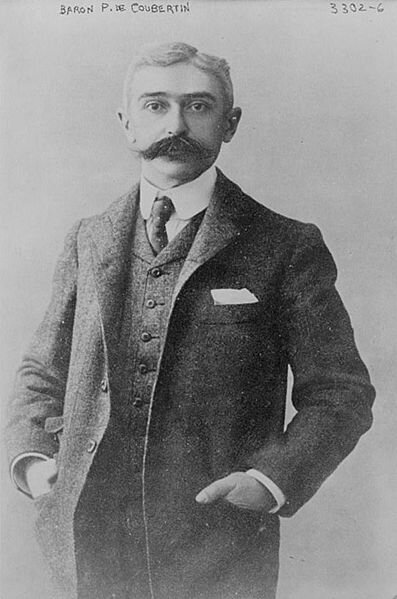

The story of the modern Olympics starts with Baron Pierre De Coubertin. He was a complicated man – an educator, historian, philanthropist, he spoke multiple languages, traveled around the world, and argued for relief for the lower classes; he also identified himself as a royalist, believed that the French monarchy should be restored, and believed strongly in the idea of separation of the social classes. A place for every man. And every man in his place.

He grew up French in the second half of the nineteenth century. He saw the destruction of the Franco-Prussian War as a young boy and was deeply troubled. He believed, like many others, that the human race was headed toward self-destruction unless measures could be taken to foster peaceful exchange, rather than hostile confrontation, between the great nations of the world. To the Baron, the idea of reviving the ancient Olympic Games brought hope. Theoretically apolitical, and devoid of the trappings of any modern religion, a reborn Olympic Games, he imagined, could be friendly, unifying displays of athletic prowess, artistic exchanges, and a peaceful space in which to resolve the thorny diplomatic issues of the day.

After all, at the height of the Ancient Games, the Greeks managed to enforce months’ long peace between hundreds of combative city-states. If they could do that without the benefit of modern communication, then what could a modern Olympics do in the era of the telegram, the Trans-Atlantic cable, and the steam engine? Could it foster a renaissance in art, athletics, and peaceful commerce?

De Coubertin a specific vision for these Games that he was determined to see realized. This probably worked to his favor, because wealthy individuals, some of them even monarchs, had been trying to revive the Olympics since at least the sixteenth century, with very little success. But the Baron could legendarily stubborn, an absolute martinet at times. Sometimes it requires a firm hand to drive innovative ideas. And in what you might call one of history’s perfect storms, these traits, at that time and place, allowed Pierre De Coubertin to succeed when others could not. With the aid of some brilliant minds from around Europe, he created The International Olympic Committee, and brought about the rebirth of the Olympic Games for a modern audience.

There was nothing about the Olympics that the Baron took more seriously than his belief that these new Games should be amateur contests. The Olympics allowed for people of all countries and all classes to compete on an equal field, to represent the best and highest ideal of the classical citizen – one part laborer, one part scholar, one part athlete. The Baron would have it no other way. He considered other “amateur” events to be too classist, restricted to members of exclusive clubs or societies. Members of the lower classes didn’t have the sort of leisure income it took to be in these clubs, which passively disqualified them.

Pierre de Coubertin thought competitors at the Olympics should come from every race, every creed, every economic class. This led to an idea that, to modern Olympics viewers, must seem very strange: At the first modern Olympics in Athens in 1896, anyone who showed up on the day of competition would have an opportunity to compete. Just about any amateur was eligible so long as they made the trip. Sometimes an event would have five hundred athletes registered, but only thirteen would actually show up.

And as for what events they would compete in? The Baron sincerely believed that sports were essential to creating well-rounded bodies and minds, but there was more to his admiration of the ancient Olympics. You see, the classical Olympics were more than sporting events: they included poetry readings, debates, art, theatre, diplomatic meetings between sworn enemies. And he wanted all of this in the modern Games.

This created an argument which, in some respects, carries on today: What constitutes an official Olympic Event? It turns out, the modern Olympics took a long time working out the kinks of what qualified. And that’s what we’re exploring in this first of two Olympic episodes on My Dark Path – the kinks of the early years. These are the forgotten, the absurd, the most unusual events run at the modern Games. Let’s see how deep we can dive – by the way, seeing how deep you could dive was one of the events…

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 16: Forgotten Games of the Modern Olympics

PART ONE

To lay some groundwork, we need to talk about the IOC. They’ve grown into a uniquely powerful and influential global organization – the Olympic Games can transform a major city, bringing the world to its doorstep with an economic impact in the billions. They even have “Permanent Observer” status at the United Nations, and the power to take the floor at General Assembly meetings. They have been rocked in recent years by allegations of corruption, and by dramatic changes in leadership; but what’s most pertinent to our story today is that, as the custodians of their own history, they’ve dabbled in some revisions, as well as some redactions. I can’t tell you how much this bothers our lead historian, Alex.

Most of the great international cultural and sporting events in the world today log everything they can to create an authoritative record – and if embarrassing truths are captured along the way, that’s the price of fidelity. If you acknowledge them, your errors can be part of the story of your progress. The IOC, though, doesn’t quite work that way. They’ve gone to great trouble to reclassify some past events as “unofficial” – even when there’s inarguable evidence that they were official at the time. They even retroactively disowned an entire Games: the 1906 Athens Olympics, which is the subject of our next episode.

I mention this because, in the early days of the Olympics, there was no effective distinction between “official” events and “exhibition” events. This made it possible to try all sorts of unusual contests. And that’s exactly what the early organizers did.

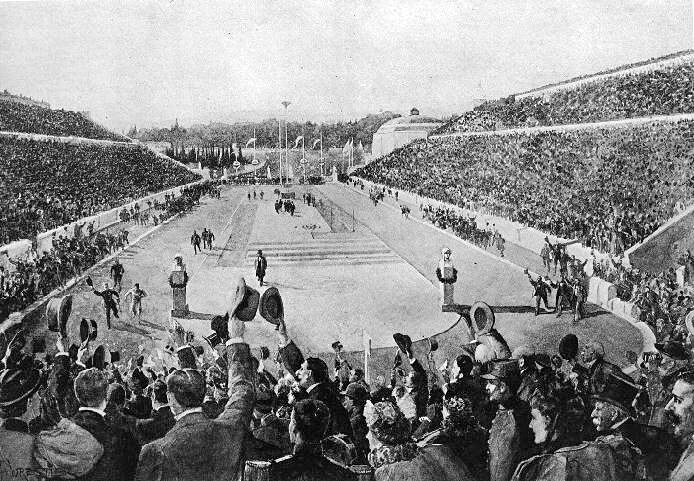

The first modern Olympics were held at Athens, Greece, in 1896. The Athenians were thrilled, but nobody knew exactly what to expect. Strangers arrived from all over the world, many without warning, to compete or observe. And a surprisingly large number of native Greeks join them. Athletes came in all shapes and sizes, from all walks of life, just as The Baron had hoped.

One of those Greek competitors was an ex-soldier called Spyridon (SPEER-OH-DON) Louis, who quickly made it through qualification trials to participate in what was supposed to be a one-time event. But we’ll get to him later.

A great many events were sports that have become part of the standard Olympic canon. Boxing, Swimming, Fencing, the Discus, Shotput, Distance Jumping, and of course the standard by which all Olympic events are judged: Olympic Rope Climbing. You heard me correctly. Your worst memories of Gym Class or Boot Camp were recreated on an international scale.

It’s as simple as it sounds. A smooth, un-knotted rope, fourteen meters long, was hung from an elevation of just over that length. The competitors had to begin in a seated position, and pull themselves up a smooth, un-knotted, fourteen-meter rope, using only their arms. An instrument similar to a tambourine was at the top, and they had to strike it to finish the climb. And - they only got one try.

Competitors were judged on their speed as well as their form – the records aren’t thorough enough to explain what good form meant, so perhaps a slow climber might make up some points by showing a flair for the dramatic.

Five competitors showed up for the first Olympic Rope Climb. Only two of them – both Greeks – made it to the top. The third-place winner, a German, became a medalist without even reaching the tambourine. The official record doesn’t show how much time he struggled, just how far he made it – 12.5 out of 14 meters.

Spectators apparently loved the event – the incredible exertion, the sense of triumph from reaching the top. But even the competitors with climbing experience complained that the distance was too great, and that the smoothness of the rope made the task nearly impossible.

So the IOC kept the Rope Climb, but started to update the rules. The event was held four more times – now the rope was just eight meters instead of fourteen, and climbers got three attempts, and were scored on their best finish. The 1904 Gold medalist, George Eyser of the United States, made it to the top in just seven seconds. His slowest competitor took eleven minutes. My arms are burning just thinking about it.

The rope climb of 1896 was popular enough that the 1900 Olympics added another rope event, one of the most ancient competitive sports that is still played on schoolyards and military bases today – the Tug of War. It’s undeniably fun to watch, whether performed by elite athletes or employees at a company picnic. And it’s confirmed that it was a regular contest in the Ancient Olympic Games, where the men who rowed the banks of oars in ancient Greek galleys were said to have a distinct advantage.

Olympic Tug of War featured two teams of eight men per side, pulling against each other on a long, wide hemp rope. The objective was to pull the opposing team six feet in your direction within a timed round. If neither team could complete this, a further five-minute sudden death was permitted. I can’t imagine the level of exertion it would take to constantly pull against another team for a five full minutes; some of them probably felt like the phrase “sudden death” could become literal.

The powerhouse in the Olympic tug of war were the British. They have a strong history of amateur sport and sports education that helped inspire Baron de Coubertin’s Olympic vision. On top of that, the British Tug-of-War teams were usually made up of constables drawn from the City of London Police.

Tug of War started at Paris in 1900 but lasted all the way until the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp; and in that span the British won two gold medals and a silver, and set an example as they did of the sort of working class athlete that De Coubertin so admired.

PART TWO

About those Paris Games. The second modern Olympics is where some of our favorite unusual events rear their heads. The City of Light is where Pierre de Coubertin had always hoped to re-launch the Games; we’ll discuss how they ended up in Athens in our next episode.

Now in case you weren’t aware, the French are a fiercely patriotic people – remember how they pressured the Walt Disney Corporation to change the name of their theme park from Eurodisney to Disneyland Paris. Well, this helps explain a lot of the Paris Olympics. The organizers were determined to create an event that the French could be proud of. What they produced is practically unrecognizable to what we’d consider the Olympics now; but it was undeniably French, and therefore provides a bounty of strange sports, most of which were never attempted again.

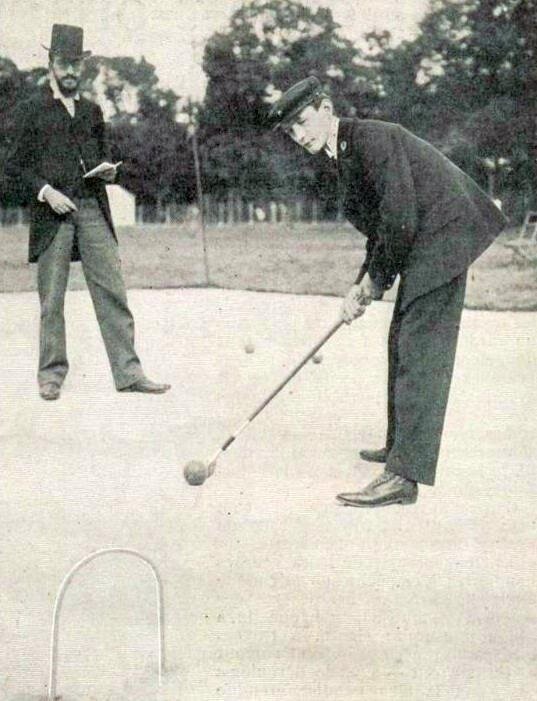

For example, this is where croquet came to the Olympics for the first time. Now there are elements to this event that were very progressive for the time. Instead of separating the divisions by gender, men and women were allowed to compete with one another or as mixed teams. Alas, on the day of the competition only ten people showed up to play: seven men and three women. And as a further problem, all the competitors who showed up were French. It’s hard to call it an international competition when only one country is competing.

There were players in other countries, but they complained that the Croquet being played was specifically a French style, with rules and customs unfamiliar to other players. While we don’t know everyone’s personal reasons, it’s reasonable to guess that some registered competitors looked over the rules and decided that the deck was stacked too much against them to bother traveling to Paris.

Of these ten French competitors, eight of them won medals. This did wonders to fatten the medal count for France, but at the cost of other nations seeing the whole affair as a farce.

When Croquet returned at the 1904 Games in St. Louis, it was a different variation on the game, known as Roque. But once again, this version of the Game was largely unfamiliar to players outside North America. This time only four people showed up to play – all of them Americans. It’s not hard to guess which country took the medals. One of the issues we continually see in these early Games is that the lack of consistent international standards led to disappointing, lopsided, or just plain strange outcomes.

Croquet never appeared again as an official event, though a proposal was apparently made in the 1920s for a sort of women’s only “bicycle croquet” event. I think that sounds sort of delightful, if potentially chaotic.

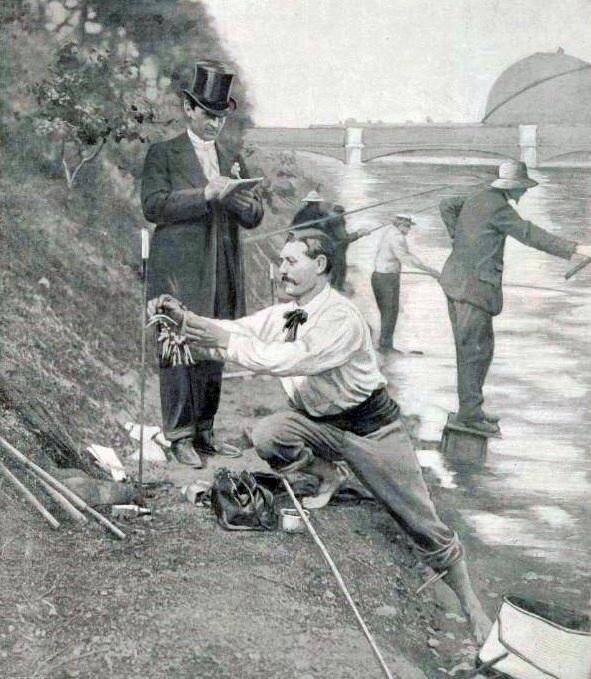

If organizers had a hard time attracting competitors for Olympic croquet, they had the opposite problem for another event in the Paris Games – Olympic Angling. That’s right, fishing with rod and reel was an Olympic event, with medals awarded and everything. Fishing was an enormously popular pastime in the French countryside, and when word spread of an Olympic contest, 600 competitors showed up, and over 560 of them were French. Remember, just about any amateur who wanted to, could be an Olympic athlete for a day.

Like croquet, this was another event that allowed women to compete either alone or in mixed teams. Competitors were judged on the largest fish caught, as well as the quantity of fish caught. One heat was held for all the non-French anglers; three more heats for all the French people who weren’t from Paris, and the final two heats were all Parisians. This narrowed the field to 57 finalists; one of them a woman who is only identified in the records as “Madame B”. Among them, they caught 887 fish, all of which were thrown back, and won a total of 3800 francs.

Although records are vague about whether this was considered an official event or simply an exhibition, most sources say that medals were provided for the event. Sadly, we don’t know what happened to them, or even who won them. They might still be out there, Olympic Fishing Medals hiding in a curio cabinet that belonged to someone’s great grandmother.

We can’t say why Olympic fishing never returned to the Games – it obviously had plenty of interested participants. Maybe it lacked excitement as a spectator sport. Or maybe, another event at the Paris Games turned people off to the idea of events that involved doing harm to living animals.

Not once, but twice, the Paris Olympics held a Pigeon Shooting competition. With real pigeons. There were 166 human participants. There were thousands of pigeons.

We don’t know the specifics of the rules: what sorts of firearms were permitted or prohibited? Modern Olympic shooting events painstakingly define what constitutes a legal weapon, from the weight of the stock down to the length of barrel and the width of the bore. Olympic Pigeon Shooting seems to have had no such restrictions – some surviving photographs depict men with pistols, yet one of the champions, in a publicity photograph, is holding a lever action rifle.

We do know that victory was defined by the number of pigeons shot. Six birds were to be released “approximately twenty-seven meters” from each competitor. The shooter had to down at least two birds in order to qualify for the next round. A hefty prize of 20,000 francs would go to the winner.

The athletes in this event seem to have treated it as a semi-formal affair. Rather than practical attire, men wore high fashion sporting clothes with waistcoats and jackets. Some even wore top hats. Their snappy outfits created quite a contrast with the carnage of the event. At least three hundred birds were killed, and attendees described blood and feathers flying everywhere, while fashionable men doffed their hats to one another and exchanged witty remarks. It sounds like an old Monty Python skit.

The champions of the two events were a Belgian called Leon de Lundun, who bagged twenty-one birds; and Australian Donald McIntosh, who killed twenty-two. It’s a wonder that any pigeons still live in Paris.

(An odd side note: there was also a Pigeon RACING event at the Paris Olympics. Though we’re assured the two competitions were unrelated, and that the racing pigeons didn’t have to fear being shot.)

This is one of those examples of revised history we told you about. The modern IOC now claims that Pigeon Shooting never really was a “true” Olympic event. But there’s ample evidence that the IOC at the time thought otherwise, as did the participants. It’s a gruesome thing to have on the record; but the point of a record is that it’s supposed to be thorough.

Anyway, not every sport at the 1900 Paris Games was violent or unfairly slanted towards the host country. Some were genuinely innovative. Like Obstacle Swimming. This is a sport which swimmers still compete in today, but it only appeared as an official Olympic event this one time.

Obstacle swimming is just what it sounds like – competitors must negotiate an aquatic obstacle course, populated by things that might naturally be found in the water: boats, pilings, sand bars, and natural barriers like sunken rocks and trees. Supposedly, the idea originally came about after a competition held in the Thames (TIMS), the great river that runs through London.

Swimmers who entered this event in Paris had to swim a two-hundred meter course and negotiate three significant obstacles: climb over a pole, then over a row of anchored boats, and for the final challenge, another row of boats, only this time, the swimmers had to go under them.

Only twelve swimmers from five countries entered the event; and while we can’t say for certain why, it’s worth pointing out that the race was held in the Seine, the river that runs through Paris. The Seine is not renowned for cleanliness, and it was far worse in 1900, arguably toxic. It’s standard in these events to have to swim against the current, but in this race, the competitors were also swimming directly into the outflow of the Parisian sewers. If any of them felt any disgust or illness from this, it’s lost to history; though some did complain that it made the river current artificially stronger. The Gold ultimately went to Australia’s Frederick Lane, who completed the course in two minutes, thirty-eight point four seconds – just two seconds ahead of Otto Wahle of Austria-Hungary.

The Paris Games also featured Underwater Swimming - a race to complete laps while completely submerged. This sounds like a challenge worthy of some truly elite athletes, but apparently it didn’t work so well for spectators – they couldn’t see what was happening. Even the judges could barely see. As with Obstacle Swimming, this experiment didn’t make it out of Paris.

***

The water inspired a great many Olympic experiments, so let’s cross the ocean to see some more. The year is 1904, and the St. Louis Olympics are being held alongside the 1904 World’s Fair. The Games are struggling to attract attention, so the organizers experiment with some new and hopefully exciting sports. They seize on one event which has been growing in popularity in the United States and Great Britain. It’s a diving event – but unlike other events, it’s not about what you do in the air. This event is known as “Plunge for Distance.”

The rules state that the athlete is to dive from a stationary platform approximately eighteen inches above the water. Upon entering the water, they must glide, face down as deep into the water as they can go without any assistance from their arms or legs. Whomever reaches the greatest depth in sixty seconds, wins.

As an Olympic event, it’s something of a bust. As with that Underwater Swimming event, it doesn’t offer much for spectators. Only five athletes register – and every one of them is a member of the New York Athletic Club; which makes it neither international nor fully amateur. To win the Gold, William Dickey makes a dive of sixty-two feet and six inches. That sounds like a lot, though it doesn’t approach the world record at the time, which was seventy-nine feet, three inches.

Once the eyes of the world focused on Plunge for Distance, people had a hard time buying into it as a legitimate sport. Our favorite summary of the whole spectacle was published by John Kieman of the New York Times in 1924. Quote:

“not an athletic event at all, but a competition favoring mere mountains of fat who fall in the water more or less successfully and depend upon inertia to get their points for them.”

An 1893 English book entitled, “Swimming” describes it thusly,

“(the diver) moves about thirty or forty feet at a pace, somewhat akin to a snail, and to the uninitiated the contests appear absolute wastes of time.”

Despite all the fun critics have had at its expense, it has actually regained some popularity. Some dedicated fans are even trying to get it returned to the Olympics. In 2016, several Olympic divers and swimmers were approached, and admitted fascination with the idea and an openness to trying it. Some have already been participating in informal events. So maybe it’s possible we’ll see these plunging divers resurface in our lifetime. Pun intended.

***

When a really talented athlete moves through the water, it’s uniquely beautiful. The subtlest movements can be almost poetic. This is part of the reason why aquatic events have been popular since the revival of the Games.

No doubt you’ve experienced Synchronized Swimming. This remarkable combination of swimming, dance, and gymnastics was invented in 1907 by an Australian ballerina and underwater performer named Annette Kellerman. The challenging choreography can appear utterly spectacular when performed by elite competitors; but it requires years of planning and practice to be competitive at the Olympic level. And by the way, if you want to be a synchronized swimmer, you need to present a new routine at every international contest – very few sports require this. It’s also one of the few Olympic events in which only women compete.

Perhaps because of that last fact, Synchronized Swimming has struggled to gain acceptance as a, quote, “real” sport, when compared with events like the javelin throw. Another unusual Olympic event may have also hampered its reputation – Solo Synchronized Swimming. Like Synchronized Swimming in groups or pairs, the goal is to perform an elaborate aquatic dance routine to music. Only here, a swimmer performs alone, and is judged by their execution and timing with the music. Now, this is how Annette Kellerman originally performed as she pioneered the sport. But for audiences, and the IOC, it just didn’t rise to the level of an event they wanted to see. It was tried at the 1984 Games, and continued on in ’88 and ’92, but was discontinued as a distinct event after that.

It makes me think back to that definition of the amateur Olympian. In a solo event, anyone with enough enthusiasm could certainly jump into a pool and splash around; whereas a highly-synchronized team is likely to need some major support. But the latter is absolutely the more exciting contest. So is this a case where the Olympics developed an event that went against the original vision? Did the original vision need to evolve in order to respect what its audience wanted?

This seems like the right time to get a little perspective, by stepping outside of the question of how we define Olympic Sports. Because, as we said at the beginning, the idea of reviving the Olympics was that many events would not be sports at all. So let’s discuss the cultural Olympics, the artistic Olympics. They’re not well remembered, now, but they played a pivotal role in the development of the Games we enjoy today.

PART THREE

In the original ambition for a modern Olympic Games, an Olympian wouldn’t just be an athlete. An Olympian could be a philosopher, a scholar, an actor, a dancer, a sculptor, a painter, an engineer. The best and brightest from all the nations of the world.

Even after he finished the Herculean effort of establishing the Olympics, Baron de Coubertin worked hard to introduce an Arts Program.

This wasn’t easy. The Olympics were already proving to be an enormous financial burden for their host countries, and the additional expense and logistics of a separate Arts Program proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. Serious planning was underway to include them at the Rome Games of 1908, but when the Italians were forced to step down as hosts and the Games quickly relocated to London, every resource was required just to ensure the Games happened at all. But his vision finally was realized at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden.

The rough framework introduced in 1912 had five divisions: Architecture, Literature, Music, Painting, and Sculpture. There were three basic rules.

All Art should be completed before the games. Not surprisingly, spectators didn’t want to watch paint dry.

An Art project should be original, produced for the Olympics and neither published nor displayed prior to the Olympic games in which it had been entered.

The project had to be inspired in some way by sport.

Beyond that, the possibilities were broad. Your saxophone solo could be competing against a symphony. This worked out alright the first time, when there were only 35 competitors in the entire program. But the more it grew, the more important it was to start drawing distinctions.

Gold, Silver, and Bronze medals were supposed to be awarded in all of these categories; though when they actually happened, some competitions had no medals, and instead awarded contracts, commissions, cash prizes, and the like. In a strange wrinkle to the rules, an artist could actually enter multiple works of art – making it possible for one person to win all three medals in a single competition. We don’t see an indication of this happening, but it was a weakness that critics were all too eager to point out.

The Arts Program divided Olympic spectators. At the 1920 Games in Antwerp, Europe was still deeply traumatized by the Great War which had just ended months before; with Belgium’s countryside ravaged as part of the Western front. An Arts Program felt like a hollow sideshow. But as time passed in that period between the World Wars, there was a mini-renaissance in the arts; cultures and communities seeing the value of them in bringing back our collective humanity.

When the Olympics returned to Paris in 1924, the Arts Program grew significantly in popularity. From 35 entries in 1912, it now saw almost 200. Some of them even came from the Soviet Union, which was otherwise boycotting the Games.

And by the Amsterdam Olympics of 1928, 200 entries became 1,100. And in 1932, as the Olympics came to Los Angeles for the first time, the Arts Program reached its zenith.

It’s not often discussed, but the Sports side of the 1932 Games was something of a disaster. Los Angeles wasn’t really a global city yet, the West Coast of America was still developing and the whole county had a population of just 1.2 million – that’s smaller than Detroit was. And the worldwide Great Depression cost a lot of people their ability to travel. Los Angeles found itself with beautiful, world-class athletic facilities that were half-filled; with many of the best athletes on Earth stuck at home.

The Arts, however, were a completely different story. Arts entries were publicly displayed at the Los Angeles Museum of Science, History, and Art, near the Campus of the University of Southern California. And for the first time ever, the Arts drew more fans than all of the Sporting events, combined. More than four hundred thousand people visited the museum, with lines wrapping around the block. It was easier, and cheaper, to send a painting to L.A. than a person; and easier and cheaper for a visitor to stroll through a museum than go to the Olympic Stadium.

The Arts Program had become much more diverse since its origins. There was even a fiercely-contested Olympic Event for City Planning. Music was divided into multiple categories: Instrumental, Orchestral, and a combined category for Solo and Choral Music. When the Olympics moved on to Berlin in 1936, the public was permitted to attend grand performances of the Musical Division entries.

And the irony is, the booming success of this alternative to Olympic Sports helped to bring about its demise, because it forced a question that has lurked around this entire story – what was the actual definition of an Olympic amateur?

***

In 1928, the IOC made a fateful decision – Artists who entered their works into the Olympics would be allowed to sell those works at the Games. It must have made sense at the time – for many of these works, this would be their brightest spotlight, and their biggest audience. This would be the moment they had the most value. This decision paid off handsomely for many artists, so much so that some began to exhibit their works in Los Angeles prior to the opening of the Games, hoping to get the advance attention of wealthy bidders. This was clearly forbidden by the rules of the Arts Program, but the IOC failed to put a stop to it. Controversy began to spread, with some IOC Members arguing that for this reason, the Arts Program needed to end. Their argument was briefly tabled, due to the Second World War.

The first post-War Olympics happened in London in 1948. They were known as the “Austerity Games,” because Great Britain, and most of Europe, were still suffering from shortages. With nearly all of their citizens rationing, the British Games needed to be held on a very limited budget. While the Arts Program was welcome overall, the sight of artists auctioning off their works to the wealthy came off as vulgar. The IOC decided it was time to make a real study into who had been entering these Arts contests.

The results of their 1949 report were either stunning, or not surprising at all, depending on your expectations. It turned out that the typical Arts Program entry did in fact come from a person who made money in the field where they’d submitted. In fact, the overwhelming majority of Olympic artists were professionals, and their numbers had steadily grown over time.

With the idea of amateur competition still so important to the core message of the Olympics, this was simply too much for critics. The arguments were fierce. Didn’t this violate the spirit of the Olympics? But how could an artist talented enough to compete globally manage to never make a penny from their work? How could they have time to produce great art if it wasn’t earning them money? It was the same argument that was happening in the Sports Program; only in this case, the evidence was impossible to ignore.

In retrospect, it was naïve to imagine someone could engage in the sophisticated Architectural work of City Planning as a completely amateur hobby. Perhaps the Arts Program had simply outgrown the ability to hold onto this pure and stubbornly-held vision.

The IOC was deadlocked over this debate. Neither side could muster a majority, and neither side would budge. This gave the Arts Program a stay of execution, and it was scheduled for the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki.

Artists began to create their entries. Some even submitted early. And then, an unexpected hitch. Finland was financially exhausted from two wars with the Soviet Union. They determined that they could afford to fund an Arts Program or a Sports Program, but not both. They chose Sports. The Arts Program was demoted to an informal exhibition. Artists would be welcome to attend, and their work would be placed on display. But there would be no judging, no prizes, and little to no promotion. The exhibition was appreciated, even successful by its drastically-diminished standards. Most importantly to Finland, it cost virtually nothing.

This is another case where the Arts Program may have been a victim of its own success. The IOC reconsidered the matter, and reached a final verdict. Going forward, the Arts would be confined to an Exhibition at the Olympics, no competitive program, no prizes, no worries about who was an amateur and who wasn’t.

In both Sports and the Arts, it seems as though it was hard to reconcile Pierre de Coubertin’s dream of amateurism with the reality of elite global competition. Did the humble commoner capable of superhuman feats ever exist at all? Well, in at least one legendary case, the answer is yes. Let’s go back to the first modern Olympics, Athens in 1896, and that ex-soldier we mentioned named Spyridon Louis.

PART FOUR

The race known as the Marathon commemorates a pivotal moment in the history of the Western World. In 490 B.C., an army of allied Greek soldiers defeated a massive invasion by Persia at the plain of Marathon. This one victory arguably saved Europe from domination by the Persian Empire, and allowed the seeds of Democracy to spread from Athens.

At the time of the battle, the entire Athenian Army was at Marathon, while the Athenian Navy was trying to block the Persians from getting any reinforcements. The city-state of Athens itself was undefended. Citizens were terrified: the Persians were known for burning down hostile cities, looting their wealth, and enslaving their inhabitants. If the Greek allies lost at Marathon – the city was likely doomed.

But when the Greeks won, a soldier called Pheidippides (PHY-DIP-ID-EEZ) was asked to do the impossible: run from Marathon all the way back to Athens to announce that the Persians had been defeated. Over the last two days, Pheidippides had already run something like 150 miles, carrying messages across the front lines. But he accepted his duty, and after running over twenty-five miles to Athens, he uttered the words “We are victorious!”, and then collapsed from exhaustion and died.

Some of the details of this story have been colored by legend over the years, but the battle and its stakes were real, and the story of Pheidippides and his sacrifice are as important to Greek culture as Paul Revere’s midnight ride is to Americans.

The Marathon footrace at the 1896 Games was designed to celebrate that event. It was a matter of immense pride to the Greeks, and several former and active Greek soldiers entered. Spyridon Louis was one of them. He had a good military record, and it seems he was encouraged to enter the race by a former commanding officer. Some accounts say that he was an itinerant worker who did odd jobs, while others claim he was a shepherd. It’s possible he did both in the years after his service – but it’s certain that he never belonged to any of the elite sporting clubs that Baron de Coubertin criticized.

He was an unknown when he entered, but people who were there remember him assuring anyone who asked that he would win. His confidence was charming but didn’t seem warranted - during his qualifying run, he finished fifth. There were well-known Greek and French runners on the course who were much more favored.

Spyridon began with a slow and steady pace, an unembellished style that surprised other runners. But he had a plan. He had carefully studied the course, plotted out how to use his own capabilities against the local terrain. This race had never been run before; but when it started, he knew exactly how he was going to run it.

As the miles went by, the race leaders, the ones who had set such a fast early pace, started to fade. Some gave up. And, slowly but surely, Spyridon Louis gained ground. His tactics were better than other peoples’ muscles.

Incredibly, halfway through the race, he stopped for a breather at a town along the route, where he was treated to an orange and a glass of cognac. He wasn’t even in the lead, but he thought it was the right time to catch his breath. Observers asked if he thought he would catch up to the others; and Spyridon predicted that he would finish well.

About 2/3rds of the way through the race, the leader was Australian George Flack, an experienced runner who had performed well in the 800 and 1500 meter races earlier in the Games. But at this distance, his inexperience began to show; and the confident, methodical Greek was right on his heels. Then, George Flack collapsed, and signaled that he could continue no further.

Spyridon had left all the remaining competitors far behind him, and as the news traveled down the course towards the Stadium, a cry of “Hellene! Hellene!” erupted among the amazed Greeks. As he entered the Panathenaic Stadium for the final lap of the race, he was joined by Princes George and Constantine, sons of the King of Greece. When he crossed the finish line, wild celebrations broke out all over Athens.

Here’s the official report from the 1896 Games. Quote:

“Here the Olympionic (sic) Victor was received with full honor. The King rose from his seat and congratulated him most warmly on his success. Some of the King’s aides-de-camp, and several members of the Committee went so far as to kiss and embrace the victor, who was finally carried in triumph… under the vaulted entrance.” End quote.

It's important to remember that Greece had long been under the control of the Ottoman Empire, and had only tasted their own freedom for less than fifty years. Recovering from their fight for freedom, and violent internal revolution, meant that they didn’t have much wealth or modern infrastructure. The victory of Spyridon Louis was a galvanizing moment of national pride, the perfect cap to their re-introduction of the Olympic Games.

Spyridon enjoyed the life of a national hero. Funny fact about the first Modern Olympics – winners received silver medals, and runners-up received copper. Gold was considered too ostentatious. Nevertheless, the IOC officially recognizes Spyridon Louis as a Gold Medalist. He also received many impromptu gifts of jewelry and cash. A local barbershop awarded him free shaves for life. He was also given a goat. We don’t know what, exactly, became of that goat. We can only hope that he and Spyridon had a long, wonderful friendship.

PART FIVE

Spyridon Louis was the arguably the first hero of the modern Olympics. His victory vindicated Baron de Coubertin’s ideal of the classical amateur. A commoner who came in from the fields for a few days, and mastered a field of champions from across the world. He never appeared on a Wheaties box, never signed a deal to endorse sneakers. He just ran 25 miles faster than anyone else could, and became a legend so powerful it turned a one-time spectacle into one of the world’s most popular athletic endeavors. The word “marathon” itself became synonymous with a long, grueling trial, with triumph waiting at the end.

The Olympic Arts Program went in the opposite direction: the more popular it became, the harder it was for amateurs to even participate. Perhaps if a few strokes of history had gone in another direction, it would have survived; or maybe the quirky and singular opinion of one man was never going to last as the Olympic movement grew. You have to wonder whether the global popularity of the modern Olympics today would have pleased him; or if the spectacle of professional athletes achieving feats impossibly out of reach for any amateur would have brought him grief.

Amateur athletics still happen all over the world today, and they’re where any future Olympian discovers their gifts. And that vision of a renaissance person, well-developed in both mind and body, is absolutely a worthy one. The Games inspire people to better themselves, they bring entertainment and joy, and they do let athletes from over 100 nations march into the Olympic Stadium as equals.

War, economic calamity, the disputes of powerful leaders and the twists of historical fate, they’ve all shaped the Games. So have its success, and the appetite of its worldwide audience. Even the strange, often funny experiments we’ve shared here in trying to define an Olympic Event changed the character of the Games as they grew. But at least something of that original vision still remains.

In 1912, the Gold Medal winner for poetry in the first-ever Olympic Arts Program was called “Ode to Sport”. One passage reads:

“O Sport, you are Justice! The perfect equity for which men strive in vain in their social institutions is your constant companion. No one can jump a centimetre higher than the height he can jump, nor run a minute longer than the length he can run. The limits of his success are determined solely by his own physical and moral strength.”

“Ode to Sport”, by the way, was written by amateur poet Baron Pierre de Coubertin – founder of the Modern Olympics, and Olympic Gold Medalist. He submitted it under a pseudonym, but won’t we always wonder just how anonymous his work really was?

***

One last morsel we wanted to share but couldn’t find a proper place for. Shooting events have been a part of the Olympics since very early in their existence. They’ve never faced any question about their legitimacy as a sport. Marksmanship is a rare skill.

But you might be surprised to learn that, very briefly, the Olympic Games attempted to introduce dueling. In the 1906 Games in Athens – the ones we’ll talk about next time which are no longer considered Olympic Games - there were two Pistol Dueling events.

Both were held at a range of twenty meters. The first event was untimed: shooters were judged for accuracy and style rather than speed. The second event was a rapid-fire pistol event called “Au Commandement” (OH COMMAND-MAUNT). At a signal from the judge, the shooter would indicate his readiness, raise his gun from his hip, and at a three count, open fire at a rate of up to 100 shots per minute, using an automatic pistol. At the end of the allotted time, the shooter was ordered to cease. Rankings were determined based upon how many shots struck the target during the rapid-fire event.

Just to reassure you, they weren’t shooting bullets at a living person. Actual dueling was outlawed in most of Europe by then. So Olympic duelists shot at specially-prepared dummies, who were dressed in frock coats. We wish we could have been there.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Ashley Thomas and Evadne Hendrix; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by our lead researcher, Alex Bagosy. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.