Episode 22: Reflections on JFK

On October 26th of this year, government agencies have a deadline to finish a review of all remaining documentation related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, The last of four American Presidents to be murdered in our history.

We wanted to mark the occasion by taking a different approach. There are so many more stories to tell than the story of murder itself; moving, fascinating stories, even funny ones. We decided to zoom in and draw some of them out of the fog to share with you. What we found were stories about a telephone, a pink dress, and a comedian. Each of them, immortalized by the events of November 22, 1963; and each of them, in their own way, reminding us of the deeply personal dimension of this day that the world has never forgotten.

Listen To Learn More about:

The Journalist who published the story about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy

Jackie Kennedy’s Famous Pink Channel Suit

The Comedian who brightened the audience morning

President John F. Kennedy

Kennedy's Arrive at Dallas 23 November 1963

Lenny Bruce

Merriman (Smitty) Smith

JFK and family in Hyannis Port, 04 August 1962

Lenny Bruce arrest

Re-imagination of Kennedy's Parade

Chanel Haute Couture Jacket, 1961

Jackie Kennedy Deplanes from Air Force One 23 November 1963

Lyndon B. Johnson taking the oath of office, November 1963

Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy in the official top-down vehicle on Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963 .

Jackie Kennedy Wedding Day

John F. Kennedy Watercolor

George Dealy Statue

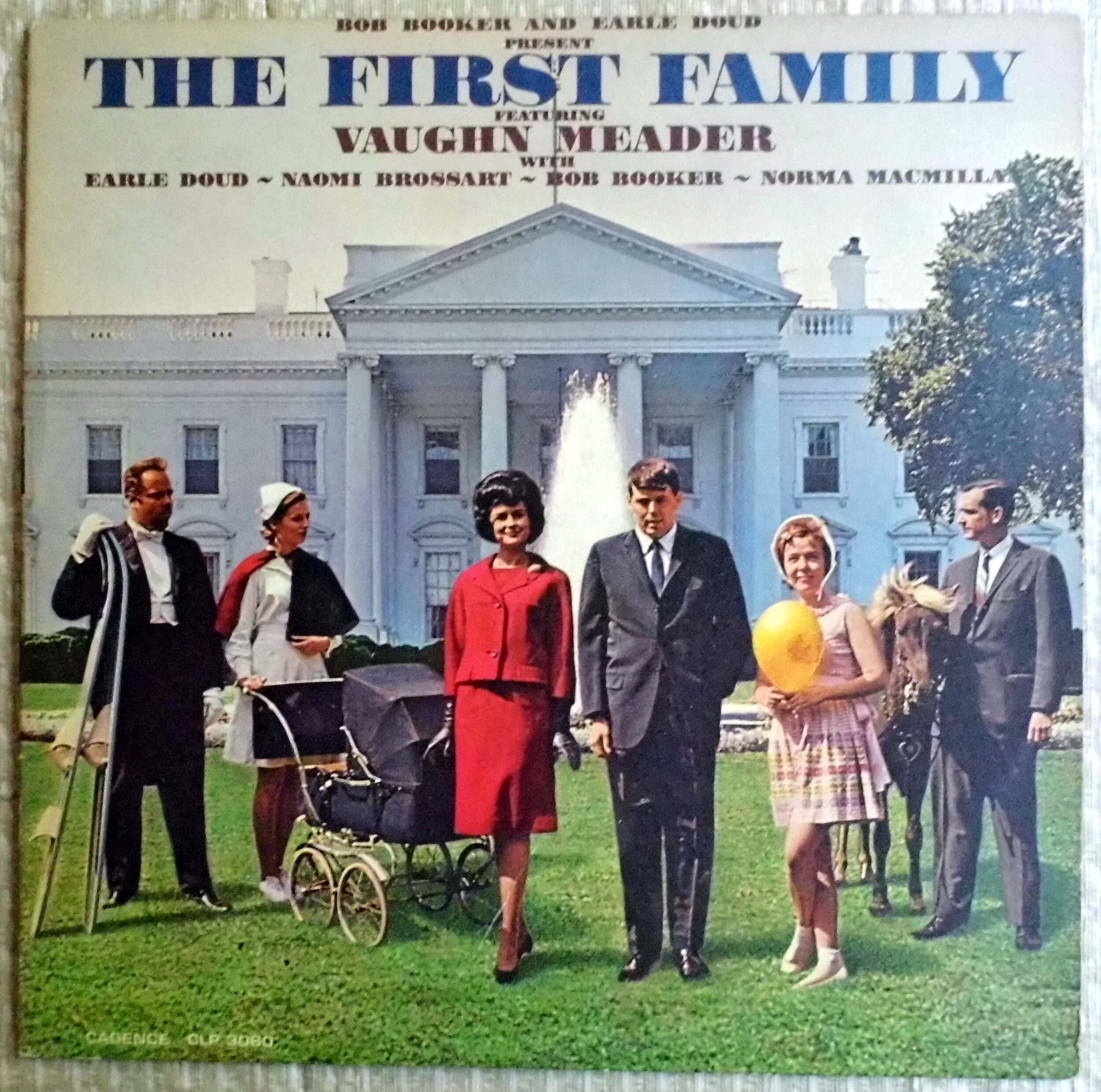

Vaughn Meader's comedy sketch poking fun of the Kennedy Administration

Sources:

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING/MEDIA:

Merriman Smith:

Pulitzer: Merriman Smith’s Account JFKs Assassination

UPI: Merriman Smith’s Account of JFK’s Assassination

Observer: How the Assassination Story Broke

Handwritten note from President Truman to Smitty about one of his articles

The Pink Dress

Millercenter: President Kennedy Essays

Crfashionbook: Chez Ninon History

NPS: Museum Exhibits Eise Fashion

Crfasionbook: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Secret Moments

Viva: The Jackie Look Has Never Gone Out of Style

Google Books: Heritage Photography Auction

Seattlepi: Jackie’s Blood Stained Pink Suit is a Sacred Relic

Crfashionbook: Jackie Kennedy Fashion Designer

Lofficielusa: Who was Oleg Cassini

Amazon: Coco-Chanel Legend by Justine Picardie

Britannica: Eleanor Roosevelt Biography

Reactions to the assassination in Popular Culture:

Roger Ebert, “Great Movies: JFK” (April 29, 2002).

Devin Faraci, “The Man Whose Life Was Ruined by the JFK Assassination” (Nov. 22, 2013)

Jim Garrison, On the Trail of the Assassins (Sheridan Square, 1988).

Barbara Garson, MacBird! (Grove Press, 1967).

Stephen King, 11/23/63 (Gallery Books, 2012).

Elisabeth Kūbler-Ross, On Death and Dying (Simon & Shuster, 1969).

J.J. Marric, Gideon’s March (Walter J. Black, Inc., 1962).

Dan Mishkin, Ernie Colón, and Jerzy Drozd, Warren Commission Report: A Graphic

Investigation into the Kennedy Assassination (Harry N. Abrams, 2014).

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen (D.C., 1987).

Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, The Illuminatus! Trilogy (Omnibus edition, Dell, 1983).

Gerard Way and Gabriel Ba, The Umbrella Academy: Dallas (Dark Horse, 2009).

MUSIC:

Something Bad is About to Happen by Rhythm Scott

IMAGES:

George Bannerman Dealey Statue uploaded by mahanga : License

First Family Album posted by Joe Jaupt on Flickr : License

Full Script:

George Bannerman [Ban-Uh-Muhn]Dealey looms large over the city of Dallas. I mean that literally, there’s a statue of him in the West End Historical District. Although born in England, his family emigrated to Galveston [Gal-Vuh-stn], Texas in 1870, when George was just 11. He got his first job in the newspaper business at just 15, and grew up to become the powerful manager of the Dallas Morning News.

When as many as one in three men in Dallas were proud members of the Ku Klux Klan, Dealey marshaled his newspaper to denounce them in articles and editorials. He rejected advertising from oil field speculators, seeing how many people were having their finances and lives ruined by scams. And he helped found Southern Methodist University, an institution which has produced worldwide leaders in politics, business, and the arts.

His life and career weaves tightly into the fabric of one of America’s largest cities. He lobbied for a historic renovation of the site of the first home built in Dallas – which also became the first courthouse and first post office in Dallas. The massive project was approved, and FDR’s Works Progress Administration completed it in 1940. There was a proposal to name it in his honor; and George was hesitant to accept at first, but finally he agreed.

George Bannerman Dealey died at age 86, still working full-time as a giant in the field of publishing. That was in 1946; so he didn’t live to see the area named in his honor – Dealey Plaza, become internationally known as the place where President John F. Kennedy was shot.

On October 26th of this year, government agencies have a deadline to finish a review of all remaining documentation related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the last of four American Presidents to be murdered in our history. Already, more than five million pages of material are publicly available in the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records collection – we’ll put a link on our website – and most of what remains to be made public has already been partially released in redacted form. But this deadline represents a kind of last of the last. While speculation about Kennedy’s killing will continue for many years – it’s arguably the most investigated murder in history – the process of declassifying government records, 58 years after the crime, is quietly coming to an end.

We don’t have any mind-blowing new revelations for you; rather, the team here at My Dark Path wanted to mark the occasion by taking a different approach. Because what happened at Dealey Plaza wasn’t just a puzzle for conspiracy theories – it was a shocking, violent tragedy that affected a lot of individuals, as well as American culture at large. There are so many more stories to tell than the story of murder itself; moving, fascinating stories, even funny ones. We decided to zoom in and draw some of them out of the fog to share with you. What we found were stories about a telephone, a pink dress, and a comedian. Each of them, immortalized by the events of November 22, 1963; and each of them, in their own way, reminding us of the deeply personal dimension of this day that the world has never forgotten.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 22: JFK Reflected.

PART ONE

Lee Harvey Oswald shot President John Fitzgerald Kennedy at 12:30pm local time in Dallas, Texas. Four minutes after he fired his rifle, the first news report went out across the wires of the United Press International News Agency. It read:

FLASH

DALLAS, NOV.22, UPI - THREE SHOTS WERE FIRED AT PRESIDENT KENNEDY'S

MOTORCADE IN DOWNTOWN DALLAS.

You’ve heard the expression “News Flash”. To understand what the term means, you have to go back to the way information traveled back in the mid-20th century. Remember, there are no satellites, no fax machines, and certainly no Twitter. If a reporter was on the scene for an important story, they needed to reach someone in their news office, usually by telephone. Someone in their office would transcribe their words and enter them into a teletype machine; this machine would then transmit the words over telephone wires to wherever it needed to go.

The word FLASH signaled that this was a story of immediate importance; it told other reporters and media outlets to clear the wires and give priority to the Flashing story; like when you hear an ambulance siren and pull over to the side of the road to let them through. Among journalists, Flash stories were known as “earth shakers”.

Just five minutes after that first FLASH, another bulletin came from Dallas.

FLASH

FLASH

KENNEDY SERIOUSLY WOUNDED

PERHAPS SERIOUSLY

PERHAPS FATALLY BY ASSASSINS BULLET

The repetition in the words, the hedging of that word “perhaps”; it gives you just a hint of the chaos and uncertainty exploding in the aftermath of the assassination. But it also means that just nine minutes after Lee Harvey Oswald fired his rifle, newsrooms all over America knew about it. In modern times, that wouldn’t be unusual – there are cameras everywhere and we’re used to having access to live, breaking news wherever we go. But for 1963, this was almost without precedent – news of this importance breaking, and traveling around the world, faster than most people imagined it could.

And it was all because of the man who dictated those Flash messages, and many more that day – a legendary journalist by the name of Merriman Smith. And the story of those nine minutes, and the wrenching hours that followed, amounts to one of the most extraordinary stories of real-time reporting in American history.

Everyone who worked with Merriman Smith knew him by his nickname – Smitty. He worked for UPI, United Press International. This was one of the syndicated news services who sold their reporting to newspapers and TV and radio stations across the country. It was founded in 1907 by the publishing tycoon E.W. Scripps. The Associated Press refused to sell stories to the papers he owned, so he created his own rival to the AP.

UPI’s motto was “Get it first, but FIRST, get it right.” The competition between reporters was ferocious, beating a rival onto the wires by even a few minutes was considered a massive victory.

Smitty had been covering the Presidency and the White House for UPI since 1940. There’s a tradition in the White House Press Corps that their senior member signals an end to a press briefing by saying the words “Thank you, Mr. President.” Smitty started that tradition. In April of 1945, he was in Warm Springs, Georgia, where he had to file another earth shaker: “FLASH – FDR Dead”.

He was so tightly connected to President Truman that he joined him on his morning walks. Smitty would describe himself as part of, quote: “The Independence Early Rising and Walking Society”. He was in the Oval Office when Truman announced the end of World War 2. Smitty ran so recklessly in search of a phone that he fell, broke his collarbone, and still got up to call his office with the news.

When John F. Kennedy moved into the White House in 1961, he gestured to Smitty and joked: “He comes with the place.” Few journalists have ever had such a deep, personal link to the Presidency for such a long period. So, when Kennedy traveled to Dallas in November 1963, there was no question that Merriman Smith was going with him.

Smitty was abrasive, combative, he abused alcohol and pills and relentlessly bullied the reporters he competed against. And this was one of the roughest times of his life – he’d split from his wife, he was broke and feuding with his bosses over his expense reports. But no one would deny he was one of the best in the game; always looking for an advantage.

There was one press car in the motorcade; and it had four reporters in it, including Jack Bell from the Associated Press. Smitty and Bell had been rivals since the Presidential campaign of Thomas Dewey – you might remember him from one of the most famous wrong headlines in history – the newspaper that proclaimed, “Dewey Defeats Truman”.

The car had a radio telephone in the front seat. Just one way for a reporter in the car to reach the outside world. The reporters were supposed to take turns sitting in the front seat to have access to the radio telephone. But the other reporters didn’t care as much about it – they thought Smitty’s obsession with new technology was silly. So, on the morning of November 22nd, Smitty claimed the front seat even though it wasn’t his turn. The other reporters didn’t want to argue the point – this was going to be a boring day babysitting the young President as he shook hands and tried to make nice among Democratic power brokers in Texas; who wanted to fight over a seat?

When the shots rang out, these reporters were in a closed-top car in the middle of a motorcade, surrounded by screaming supporters. What was that sound – a car backfiring? Only Smitty was experienced with firearms, he’d even used handguns at the Secret Service training range while getting to know agents on the President’s protective detail. So he was the only reporter in the car who knew he was hearing gunshots. He grabbed the radio telephone, called the UPI Office, and started talking.

The President’s car suddenly accelerated in front of them, racing to get to Parkland Memorial Hospital. The press car accelerated to follow, and Smitty delivered his first Flash report of the day. Behind him, Jack Bell realized that the biggest story in the world was happening, and his rival had the only phone.

He reached over the seat, grabbing at Smitty, wrestling with him, even punching him in the head and the back, trying to get the phone. But Smitty took every blow, holding the line while his office read back his report to him, making sure every word was correct before sending it out.

When they reached Parkland, Smitty was at Kennedy’s car before they even unloaded the President. This is how he described it later:

“The president was face down on the back seat. Mrs. Kennedy made a cradle of her arms around the president's head and bent over him as if she were whispering to him.”

The human detail in those words is so remarkable to me – that he noticed and remembered the way the First Lady held her husband’s body even as he scrambled to learn what was going on.

Jacqueline Kennedy’s Secret Service detail included an agent named Clint Hill – Smitty was on a first-name basis with him and Clint was there when Smitty ran up, asking how bad it was.

Clint said: “He’s dead, Smitty.”

And here’s the incredible part – Smitty ran into the emergency room, broke into the cashier’s cage to grab the nearest phone, and sent out that second bulletin, the one I described to you earlier:

KENNEDY SERIOUSLY WOUNDED

PERHAPS SERIOUSLY

PERHAPS FATALLY BY ASSASSINS BULLET

He had a first-hand eyewitness account nobody else in the world had, but he still used that word – Perhaps. Because Clint Hill was just one eyewitness, and he wasn’t a doctor. And a good journalist gets confirmation. It was just nine minutes after the gunshots; and Merriman Smith was fulfilling UPI’s sacred motto – he was getting it first, but first, he was getting it right.

He was still dictating reports into the phone as a gurney was wheeled behind him with the President’s body.

***

Bill Sanderson, author of a book about Smith’s work in Dallas, wrote in a column that 68 percent of American adults heard about the shooting within a half-hour of it happening. Within 90 minutes, 92 percent of Americans had heard about JFK being shot. It’s now considered routine for breaking news to take over the airwaves within minutes; but for 1963, this was a revolution in reporting. All because Smitty grabbed that phone in the car and wouldn’t let go.

When the legendary Walter Cronkite broke into daytime programming to start reporting the story, CBS couldn’t show him immediately. The cameras used in TV studios back then needed 20 minutes just to warm up; so there was just Cronkite’s voice over a “Breaking News” slide. At the time, daytime dramas were performed live, so CBS interrupted a broadcast of “As The World Turns”. The actors finished playing the episode, with no idea that they had been cut off, or why.

Walter Cronkite, by the way, was a former reporter for UPI. When he described the hill in Dealey Plaza where some eyewitnesses reported hearing shots, he was reading directly from another flash bulletin. The immortal words, “grassy knoll”, were coined by Merriman Smith, who was not ready to stop reporting. Within 11 minutes of the assassination, he’d dictated a 500-word story that every UPI affiliate could publish. In that same 11 minutes, the Associated Press was just getting its first garbled bulletins out. The transcribers in the office were so shaken that the word “blood stained” came over the wires reading “blood stainezaac”.

A White House official reached Smitty and told him that Air Force One was getting ready to take off, and that he would be allowed to come if he could make it. But the Press Pool car had already left with another reporter. Smitty refused to let the story get away from him; he cajoled a police officer to take himself and two other reporters to the airfield, screaming through the streets of Dallas. He was in the room as the new President, Lyndon Baines [Bae-ns]Johnson, took the Oath of Office, the shaken widow Jacqueline Kennedy by his side. And then Air Force One took off into the sky.

As the longest day of his life came to a close, 50-year old Merriman Smith put together all his memories and observations into a full report for the morning editions. We’ve got a link on our website and you really should read it; I just cannot believe, in the midst of all this shock, that anyone could balance world-class reporting with emotionally-devastating prose the way that he did. This is how he closed the article, after Air Force One had landed back in Washington, D.C., and Smitty had been transferred to a helicopter bound for the White House.

“In the compartment next to ours in one of the large chairs beside a window sat Theodore C. Sorensen, one of Kennedy's closest associates with the title of special counsel to the president. He had not gone to Texas with his chief but had come to the air base for his return.

Sorensen sat wilted in the large chair, crying softly. The dignity of his deep grief seemed to sum up all of the tragedy and sadness of the previous six hours.

As our helicopter circled in the balmy darkness for a landing on the White House south lawn, it seemed incredible that only six hours before, John Fitzgerald Kennedy had been a vibrant, smiling, waving and active man.”

UPI submitted his article for consideration for a Pulitzer Prize in the category of breaking news. Instead, it won the Pulitzer for National Reporting in 1964. He was the first reporter to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom; became a frequent talk show guest, but all the fame, honors and accolades hadn’t meant anything to him before and that didn’t change now. His finest hours of journalism had come on one of America’s darkest days; and his mental health in the days when too many people tried to drink away their depression and trauma never improved. After he lost his son in a helicopter accident in Vietnam, Merriman Smith died by suicide at age 57 – a gunshot wound to the head. Although he never served in the military, by special dispensation, Smitty is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

PART TWO

When Smitty filed his full-length report on the assassination, he described, in the chaos of the first few minutes, seeing a flash of pink out of the corner of his eye. He knew just what that pink was, it was the only thing around that particular color – it was the suit dress worn by First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy; now one of the most famous outfits in American history. Think for a moment – can you picture what the President was wearing? It was a gray suit. Far more people remember the pink dress.

Its fame reveals a great deal about the woman who wore it – because for Jacqueline Kennedy, later Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis when she re-married, the choice to wear the pink suit dress was a powerful public statement; and the choice to keep wearing it all the way to the end of November 22nd was another public statement, from a bold woman who understood, perhaps better than her late husband, the power of image.

Jacqueline was a fashion icon during the 60’s – you might have seen her pillbox hats; big, buttoned suits; or bouffant hairstyle. But there was so much more to her, and the conscious way she worked with the spotlight that was on her whether she wanted it or not.

She was the most educated First Lady of her time; receiving all the elite schooling money could buy. She had a passion for horses and won equestrian championships by the time she was just 11 years old. She studied abroad in Paris, learned to speak four languages, and in 1951, she graduated from George Washington University with a degree in French Literature. There were so many lives available to her beyond that of a politician’s wife.

And yet, she saw clearly enough, in the 1950’s, that her choice of whom to marry would play a major role in her fate. She earned an internship with Vogue Magazine but quit on her first day; believing that being caught in associated with a work environment dominated by women might limittaint her marriage prospects. It can be hard now, to get inside the head of a woman in that time, having to weigh these competing factors in her mind – capable enough for independence, but wanting a good husband and a family and trying to make that happen as well.

She didn’t lack for options. Even when John F. Kennedy, the handsome young Congressman from a wealthy Massachusetts family, proposed to her right after winning a seat in the U.S. Senate, she didn’t say yes right away. Although she was charmed and attracted to him, shared his Catholic faith and his interest in travel and literature, she took a 30-day trip away from him to make up her mind. Details like this help to paint a picture of a deeply thoughtful woman who would not be pressured by power or by what other people wanted of her.

Now you might have guessed from her study abroad or her major in French literature that Jackie Kennedy loved all things French. She even preferred the French pronunciation of her name: “Zha-kleen.” And this love extended to French fashion, and this is important not just because of what French fashion meant to womanhood in the 20th century, but because once her husband set his eyes on the White House, it became a part of the political conversation.

Now France has been in the fashion conversation for centuries; presenting audacious styles that people thousands of miles away would learn about and try to replicate. It was a French engineer, Joseph Marie Jacquard [juh-kahrd], who invented a mechanical loom in 1801 that was capable of rapidly stitching together silk. France was already one of the world’s silk capitals – now they could incorporate this comfortable, luxurious fabric into more designs than ever.

But it was a designer of the early 20th century, Coco Chanel, who started a revolution with a simple concept – design beautiful clothing for women, that women would enjoy wearing. She saw other women as weighed down by steel buckles, stiff hat brims, heavy jewelry; she saw clothing like this literally trapping the women inside.

Chanel designs were lightweight, minimalistic by design. Instead of a hat crushed under the weight of massive plumes, she would use a single feather. Corsets and bustles were gone, Chanel wanted to celebrate the beauty of a woman’s natural figure.

For women who were just joining the working class, who could finally afford to own clothing they enjoyed, Chanel’s loose-fitting silk became a symbol of freedom and independence. They might not have been able to afford an authentic Chanel, but a legion of imitators picked up the trend – Coco Chanel was literally defining a generation of style, dressing the modern woman.

And during the 1960 Presidential Election, Jacqueline Kennedy was one of the most scrutinized modern women in the world. This was the first campaign that most Americans saw on television, and the Kennedys seemed like they were made for TV – youthful, dazzling, and charming.

Opponents tried to turn this into a weakness. They accused Jacqueline of lacking patriotism for loving French art and fashion. They criticized her tastes, saying that her lavish spending was a sign that John Kennedy would plunge the country into debt.

In a way, the opposition was right that Jacqueline Kennedy would spend money in the White House. But what she saw, and what they didn’t see, was just how politically powerful a little investment at home could be.

Jacqueline Kennedy was just 31 years old when the Kennedys moved into the White House. On her very first day, she spent $50,000 on renovations. That’s about $560,000 in modern currency, more than the median cost of an American home. But it wasn’t vanity, the First Lady recognized that this house would host elite guests from around the world, and it needed to look the part and be designed effectively for politics and diplomacy.

The traditional tables were all rectangular – Jackie got rid of them, circular tables were better for stimulating conversation. She brought in modern furniture that guests could use, while turning part of the house into a historical museum for the more traditional furniture and artwork. She even persuaded the owners of great art pieces to donate or sell them – most were thrilled to contribute something to the home of the President.

When the renovations were complete, Jacqueline Kennedy gave the nation a personal tour of the new White House on television. It was a sensation, most of the country had never had such a look inside the lives of the First Family; it elevated her profile and the profile of her husband – and showed once again that she understood the power of the modern media better than her detractors. She even wrote a book on the history of the White House, and the proceeds from the book paid for many of the renovations.

America had seen high-profile First Ladies before; chiefly the iconic Eleanor Roosevelt, who advocated tirelessly for civil rights and women’s rights. But before Roosevelt, this was more the exception than the rule – Presidential spouses were meant to support their partners in personal matters, not political ones.

Jacqueline Kennedy took the example of Roosevelt, and of President Eisenhower’s wife Mamie, and took it to the next level. She didn’t keep her issues separate from her husband’s, she became a diplomatic asset to his Presidency.

Her rich cultural knowledge, the multiple languages she spoke, broke the ice with multiple world leaders; easing up tension and opening dialogue even with notoriously difficult heads of state like French President Charles de Gaulle [Chahr-ls du Gaul]and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

One newspaper described the first trip abroad by the Kennedys like this:

“Jacqueline Kennedy has given the American People from this day on one thing they [have] always lacked—majesty.”

When they returned home, even President John Kennedy had to acknowledge her diplomatic brilliance. He described himself as, quote: “the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.”

Jacqueline Kennedy had thwarted her critics not by fighting dirty, but with savvy and persistence. She knew there was a better way to be First Lady than what they wanted for her. She did, however, make one concession – she started buying American clothing. You won’t be surprised, though, to learn that they were American versions of French fashion.

Designer Oleg Cassiani [oh-leg Ca-see-nee] was nicknamed “The Secretary of Style”. He had worked in Hollywood and he had a reputation for being able to quickly create styles that reminded people of the latest French designs. In his mind, his client Jackie was, quote, “a star in a major film”, and the role she had to play needed costumes.

Cassiani made over 300 outfits for Jacqueline Kennedy – both formal wear and casual wear. Even when she was photographed in more private settings, her outfits always helped tell the story. She even let herself be photographed in her pajamas – they looked great on TV.

She had another source for her wardrobe, though – a Manhattan dress shop called Chez Ninon. And this is where the pink suit dress enters the story; because depending on how you look at it, it both was and wasn’t Chanel.

Chez Ninon was founded by two women. Nona McAdoo Park and Sophie Meldrim Shonnard. When Nona’s husband died, she desperately called her friend Sophie for ideas on how to support herself; and the two women decided to open a dress shop.

Twice a year, they traveled to Paris, and studied all the latest trends. They weren’t copycats, per se, if they found a design they loved, they paid the designer for a license to re-create it in America, and bought all the authentic raw materials. They sewed exact copies of popular designs and sold them in Manhattan for much more affordable prices than the Paris boutiques.

You could only shop at Chez Ninon by invitation, but Jacqueline Kennedy was an honored regular customer. When America saw her wearing their outfits, Chez Ninon exploded in popularity. Kennedy’s outfits were must-haves for women all over America who wanted to stay modern and chic.

There’s a story that one high society woman was invited to the White House, and wore her best Chez Ninon dress to make a good impression. Then the First Lady of the United States came down the stairs, wearing the exact same outfit. Imagine the awkwardness.

The suit dress Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy wore on November 22, 1963 came from Chez Ninon, based on materials and patterns by Chanel. It was made from pink wool, with a navy collar, and four gold buttons in two rows of two above the waist. She completed the outfit with white gloves and a pink pillbox hat.

It was a practical and stylish outfit, and Jackie had worn it on several occasions. She didn’t normally accompany the President on trips like this, and we only have guesses as to why she was there on this trip. Perhaps she wanted to stay close to her husband – they had just lost their newborn son three months before and were still grieving. Perhaps she thought that being by his side would help calm the political tensions in Texas. The fact that she wore pink could be a statement all its own. It’s not very well remembered now, but when Jackie was born, pink was considered a color for boys. It was only during the 1940’s when the trend began of blue for boys and pink for girls.

The previous First Lady, Mamie Eisenhower, was so famous for pink dresses and pink décor that there were popular shades referred to as “Mamie Pink”.

Eisenhower had been a Republican, the Kennedys were Democrats. Maybe supporting her husband and wearing pink was an homage to her predecessor, a cultural peace offering across party lines, a way to embrace a more traditional femininity without surrendering her appreciation for modern French style. Jacqueline Kennedy always considered things like this.

But her outfit became famous for reasons she never could have imagined.

As pictures and images of the assassination spread across the world, that perfect pink dress stood out from the crowd. When it was stained with the blood of the President, it became a symbol of the trauma inflicted on an entire nation.

After the assassination, Jackie’s personal Secretary, Marry Gallagher, brought her a new dress. She thought that the First Lady should change before Lyndon Baines Johnson was inaugurated as the new President.

But Jacqueline Kennedy refused. In photographs of the inauguration, she is standing right by the side of LBJ, still wearing the bloodstained suit. She wore it through every photograph taken that day. All she said was: “Let them see what they’ve done.”

Even in the midst of the deepest shock and grief imaginable, Jacqueline was still aware that the world was watching, that the narrative of the American Presidency was unfolding, and that she was a part of it. If the First Lady was a character in a story that mattered to so many millions, she was not going to remove her costume yet.

When she finally changed clothes after the long and terrible day, she gave it to a maid, who delivered it to Jackie’s mother, Janet Lee Bouvier. Bouvier placed the dress directly in a box, and stored it in the attic, next to Jackie’s wedding dress.

Many years later, Bouvier sent the box to the Smithsonian, with a note that simply read: “Jackie’s dress”. The pillbox hat was missing; we have no record of what happened to it.

The Smithsonian has the Kennedy family’s permission to hold and preserve the dress, with the request that it not be displayed to the public until the year 2103, when it will no longer be a source of pain to the family.

It’s vacuum-sealed in a climate-controlled room, a tangible relic of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, maintained privately by the government that his wife and himself served and sacrificed for. The President’s blood is still on it.

PART THREE

On the evening of November 22nd, 1963, miles away from Merriman Smith and his typewriter, or Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy and her pink dress, comedian Lenny Bruce was supposed to go on stage at a nightclub and tell jokes. Bruce was one of the most raucous, challenging, and hilarious comedians emerging from the counterculture, willing to take on any sacred cow. Willing to get arrested for the right to use dirty words on stage. But as the hour approached for his show, suspense and expectation hung in the air. Would he even go on? Or would he just cancel the show? Would he mention the assassination? On one hand, how could he not? On the other hand, what could anyone, even a groundbreaking comedian, say at this shocking hour that would have any value?

Lenny Bruce didn’t cancel his show. He took the stage, walked up to the microphone, took a deep breath, and said: “Boy, is Vaughn [V-AW-n] Meader screwed.” Actually, depending on who tells it, he used a different word than screwed, but we’ll stick with this version for our listeners.

And, in one of the greatest miracles in the history of comedy, he got a laugh. To understand why, let’s talk about who Vaughn [V-AW-n] Meader was; and why he was definitely screwed.

Vaughn Meader was a fellow comedian, who in the era of the Kennedy Administration, had struck gold. He did a good impersonation of the young President with his broad Harvard accent and, after honing it on the stand-up comedy circuit, recorded an album called The First Family, where he and other comedians impersonated JFK and his family in skits like dinner at the White House. It was light, silly, harmless comedy – everything Lenny Bruce rebelled against – but it caught on wilder than anyone could have anticipated. At its peak, The First Family was selling more than a million copies a week; the record industry described it as the fastest-selling album of all-time; at least, until the following year when a band called The Beatles became popular.

Skits from The First Family were played on the radio instead of pop songs; it even won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year, beating records by Tony Bennett and Ray Charles. President Kennedy himself loved The First Family; according to Merriman Smith, he put a Cabinet meeting on pause to play it for everyone. At a gathering of the Democratic National Committee, he opened his remarks by saying: “Vaughn Meader was busy tonight, so I came myself.”

Lenny Bruce turned out to be 100% correct. The stratospheric success of the album meant that Vaughn Meader was inseparably linked with Kennedy in the public’s mind. And nobody wanted to hear his impersonation anymore. After the assassination, the record label pulled the album, and its sequel, from circulation, not wanting to be seen profiting from a tragedy. Meader never managed to achieve any more significant success in comedy. He wound up playing bluegrass and country music in Louisville, Kentucky, and managing a pub up in Maine.

The genius of Lenny Bruce’s joke is the way he both acknowledged the tragedy, and sidestepped it. By pointing out how the assassination of a President was going to impact the career of a rival comedian, he found one, human-scaled irony in the midst of a nightmare too immense for anyone to fathom. A single moment of distraction and release, a way to acknowledge Kennedy without saying the word Kennedy, to pivot the audience to somewhere else just long enough to laugh. Like I said, a truly remarkable moment in comedy.

It’s also the raw beginning of how American culture has processed the events of November 22nd, 1963. One way of describing culture could be to call it a conversation that a population has with itself. And a look at how our culture talks about the assassination reveals the evolution of both our narrative of that day, and our feelings about it.

Interestingly enough, popular culture had already imagined a version of Kennedy’s killing a year before it happened. British mystery author John Creasey wrote a series of mystery thrillers under the pseudonym “J.J. Marric”. They told the adventures of Commander George Gideon of Scotland Yard. The seventh book in the series was called Gideon’s March. In it, an American from the south plans to assassinate President Kennedy during a visit to London. While the President rides in a limousine as part of a parade through London, the assassin intends to set off a bomb. So while it didn’t predict Oswald using a rifle, there are enough similarities as to be eerie.

Less than a year after the assassination, the Warren Commission delivered its final report. It was September 24th, 1964. Earl Warren was the former Governor of California and the sitting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; and the bipartisan commission consisted of Senators, Congresspeople, CIA Director Allen Dulles, and a host of legal heavyweights. The report was 888 pages long, and backed by 26 volumes of supporting documents, and it concluded that Oswald was the lone assassin, firing three shots.

But as the media and the public began to read the report, obsessively questioning every incomplete thread, every footnote, every odd detail, the floodgates opened. A whole lot of people in America were not ready for this to be the end of the story.

Literally hundreds of novels, short stories, plays, films, television episodes, and graphic novels incorporate the Kennedy assassination, and virtually all of them assert that there was a conspiracy bigger than just Lee Harvey Oswald. We could go on for a long time providing examples of this, but we’ll just revisit a few.

In 1967, Barbara Garson wrote the play MacBird!, which re-imagined Shakespeare’s Macbeth through the lens of JFK’s killing. The lead character of MacBird was clearly based on President Johnson, who takes power after the assassination of Ken O’Dunc. It doesn’t suggest or even imply that Johnson had any role in the killing, but it did argue that he benefited from the assassination, and that one of the consequences was plunging the nation deeper into the war in Vietnam, just as Shakespeare’s Macbeth destroys the new peace in Scotland with his murder of King Duncan.

MacBird! ran off-Broadway for 386 performances. And I think one of the reasons it caught on with audiences is that it was an early example of a creative work which provided an answer to the burning question “Why did this happen?”

When you experience something traumatic, one of the things that makes emotional recovery so difficult is letting go of that question: “Why did this happen?” It can make us blame ourselves, or become angry and bitter at the unfairness of fate. The Warren Report was bursting with detail; but when it comes to why our President had his life stolen away right in front of us, it wasn’t satisfying. There could be more to it. There must be more to it, right? How could one unbalanced, aggrieved individual with a mail-order rifle shake the entire world like this for his own reasons? Is that really enough to kill a President?

It’s that question that became dominant in stories about the assassination; all the attempts to bring us a quote-unquote truth which would finally fulfill our gaping need for meaning.

In 1975, Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson published a trilogy of novels called The Illuminatus! These books – The Eye in the Pyramid, The Golden Apple, and Leviathan, proposed that there was a conspiracy, and that killing Kennedy was just a part of it, it was actually a much larger plot to bring about the end of the world. In these books, several assassins converged on Dallas, all trying to kill Kennedy at the same time. These books were so popular that they were adapted for stage by London’s National Theatre.

Other stories also imagine the presence of additional shooters; perhaps at that grassy knoll described in Smitty’s reports. In Watchmen, the legendary graphic novel by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, a black ops mercenary known as The Comedian is present in Dallas on the day of the assassination. The film adaptation of Watchmen takes it one step further, and shows The Comedian firing the fatal shot.

One of the most popular television shows of the 1990’s was The X-Files, whose entire milieu was conspiracy theories about government secrets and paranormal events. It’s a favorite of ours, too. In The X-Files, it’s the long-standing villain of the show, popularly known as The Cigarette Smoking Man, who is shown as the secret, extra shooter who kills JFK and gets away. The show even had a trio of recurring characters, conspiracy researchers who occasionally helped the heroes and then got their own spinoff show – and the three of them ironically referred to themselves as The Lone Gunmen.

In both Stephen King’s novel 11/23/63, and the graphic novel The Umbrella Academy by Gerard Way and Gabriel Ba, main characters travel back in time, trying to prevent the assassination.

There is even a graphic novel adaptation of the Warren Commission Report itself. Dan Mishkin, Ernie Colón, and Jerzy Drozd created it, calling it The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation into the Kennedy Assassination. Not only does it summarize the report with the help of visuals, it delves into the history of the report itself, and shows where errors, obfuscations, and more by the Warren Commission gave ample fuel for conspiracy theories from the very beginning.

It was a rejection of the Warren Commission, the belief that it was a fiction and a cover-up, which fueled the most famous, and most influential, popular culture response. In 1991, 28 years after the assassination, Oscar-winning filmmaker Oliver Stone made the three-hour epic JFK.

He started his story with a 1988 book written by Jim Garrison, the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana. It was called On the Trail of the Assassins, My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy. Jim Garrison was the only law enforcement official in America who brought real, criminal charges against someone for participating in a conspiracy to assassinate John F. Kennedy. The defendant was Louisiana businessman Claw Shaw. The jury’s verdict reported back that they had been convinced by Garrison’s presentation that there was, in fact, a conspiracy. But they didn’t believe Clay Shaw was a part of it. It took them less than an hour to acquit him.

Oliver Stone’s JFK cast Kevin Costner, one of the biggest stars in Hollywood at that point, in the role of Jim Garrison. Garrison himself appears in the film in an ironic cameo – he plays Chief Justice Earl Warren, presiding over the Warren Commission Report whose conclusions the film assaults relentlessly.

It makes use of a phrase originally coined by Winston Churchill, describing the assassination as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” As an exercise in cinematic technique, it’s mesmerizing, exhilarating, overwhelming your senses and thoughts as it barrels deep into a labyrinth of secret government meetings, anti-Castro rebels funded by the CIA, the underground gay community of New Orleans, the criminal underbelly of Dallas. It positions President John F. Kennedy was the upstanding and visionary savior who was going to take away the power of military contractors and organized crime and rogue intelligence agencies, who was going to get us out of Vietnam. And it was those forces, the movie claims, that rose all as one to steal him from us, and set Lee Harvey Oswald up as the patsy so that we would never know the truth.

The film critic Roger Ebert said of the movie JFK that it was neither historically true nor accurate, but that this was not the point. In Ebert’s words:

“His secret is that he doesn't intend us to remember all his pieces and fit them together and arrive at logical conclusions. His film is not about the case assembled by his hero, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison. It is about Garrison's obsession….This is not a film about the facts of the assassination, but about the feelings. JFK accurately reflects our national state of mind since Nov. 22, 1963. We feel the whole truth has not been told, that more than one shooter was involved, that somehow maybe the CIA, the FBI, Castro, the anti-Castro Cubans, the Mafia or the Russians, or all of the above, were involved. We don't know how. That's just how we feel.”

The film is still thrilling to watch today, and its technique has influenced basically everyone who ever set out to reveal the secret truth of the world on YouTube. Historical study has not been kind to it when it comes to the quality of its evidence. But it shows just how powerful the medium of film is, that it resonated so strongly with the grief and dissatisfaction of a country that it became a blockbuster hit.

And, arguably, it’s one of the biggest reasons we’re bringing you this episode today. It was the feverish public interest in the assassination, freshly revived by Oliver Stone’s film, which pressed Congress to pass the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992. By the time it was passed, some 98% of the documentation used to create the Warren Commission Report was already declassified, but this made it a matter of law that all remaining records, with only the most minor redactions, be made public no later than 2017. It’s now 2021, so the government did manage to drag their feet on a few thousand documents; but now, they say, we have all the knowledge that there is to have. And yet, I don’t believe for a moment that the market for alternate theories is going to die down.

In 1969, six years after Kennedy’s death, Dr. Elisabeth Kūbler-Ross published On Death and Dying, in which she charted the process by which people engage with the idea of their own mortality. We have since learned that this process is how we deal with all death; and maybe all disruptive changes in life. The five stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally, acceptance of the reality of death. You don’t take a simple, linear journey through these five phases, you might take steps forward and back, you can exist in multiple states at once; and maybe you never do reach acceptance, especially if you don’t have help and support. There’s so much available out there to send you right back to denial and anger if you don’t want to make progress.

The assassination of President Kennedy has become one of those major junction points in the story of America, where it just feels like everything after was different. It was just the first in a pulverizing series of tragedies: Vietnam, the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, even the late President’s own brother, Robert Kennedy. The tumultuous Presidency of Nixon, the Watergate scandal, the Nuclear Arms race. The so-called “Baby Boomer” generation, born right after World War 2 was right on the cusp of adulthood in late 1963. If a universal part of growing up is leaving behind childhood innocence and naïve childhood hopes, the events of November 22, 1963, and everything that followed, imprinted that lesson on an entire generation with brutal force.

So I think these cultural reactions are fascinating when we ask what state they find us in, collectively. Did Lenny Bruce give his nightclub audience just a brief moment of denial through laughter? Was it anger when Oliver Stone ripped defiantly through the Warren Report? Is it bargaining when Stephen King writes a fantasy about undoing this great wound? Now, almost 58 years after it happened, has most of America moved to acceptance about the death of John F. Kennedy? Some parts, no doubt, never will.

PART FOUR

I’ll admit we’ve been cagey in this episode regarding our own feelings about what happened, about whether there was a conspiracy, whether Oswald acted alone. With respect to the importance of getting history right, the story of Lee Harvey Oswald, lone gunman changing the world with three bullets fired from a sixth-story window; is incredible, difficult to believe in part because the odds against it ever working are so astronomical.

But what I believe is that multiple things can be true at the same time. It can be true that Oswald was on the radar of the intelligence community before the assassination, that he had perhaps even been an asset they hoped to use in the Soviet Union. It can be true that this same intelligence community could have clumsily wanted to conceal this, and lied to the Warren Commission, intensifying our distrust.

It can be true that there was unsavory, criminal collusion between our government and the Mob, and that there were rogue operations happening in the FBI and CIA without enough oversight, that some of those rogue operations were aiming to overthrow Castro and that Kennedy had worked against them. It can be true that Kennedy was wary about increasing our involvement in Vietnam and that some of his own Generals thought this made him soft on Communism, perhaps not even patriotic enough.

All of these things can be true, and well-supported by the historical record, while simultaneously, it can be true that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, and as unlikely as it was, succeed.

Is that last part true? Like I said at the beginning, you could call this the most-investigated murder in history. In a murder trial, you would need 12 jurors to believe, without a reasonable doubt. I wonder, if you put 12 Americans in a room, right now, would they vote unanimously? I don’t think they would. And so, it seems, we’re destined to continue reviewing it, ruminating on it, looking for answers at Dealey Plaza. I know I felt that curiosity when I visited. But it helps, once in awhile, to break the obsessive gaze, look around for something else to study here, like the stories we told you today. If we really want to find some ultimate wisdom, some meaning in what happened…maybe it’s actually been hiding there all along.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Ashley Whitesides and Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. This story was a group effort for our team – our senior story editor Nicholas Thurkettle covered reporter Merriman Smith, producer Evadne Hendrix wrote about Jacqueline Kennedy’s pink suit, and Kevin Wetmore took us on a journey through our collective cultural response to the assassination. Big thanks to all of them and to our lead fact checker Nicholas Abraham

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.