Episode 25: WITSEC Relocates the Mob

Join us on this week's dark path into the lives of people in witness security, and learn more about the Italian Mafia on the way.

Listen to Learn More About:

Notable Mafia members like Salvatore Maranzano, who established the five dominant Mafia families, and Joseph Barbra, a powerful mafia leader that established a famous soda company still around today

Mafia terms like Costra Nostra and Omertà and their meanings

Life inside the witness protection program

A street full of Italian restaurants similar to what Nick saw on his trip through the South West of the United States

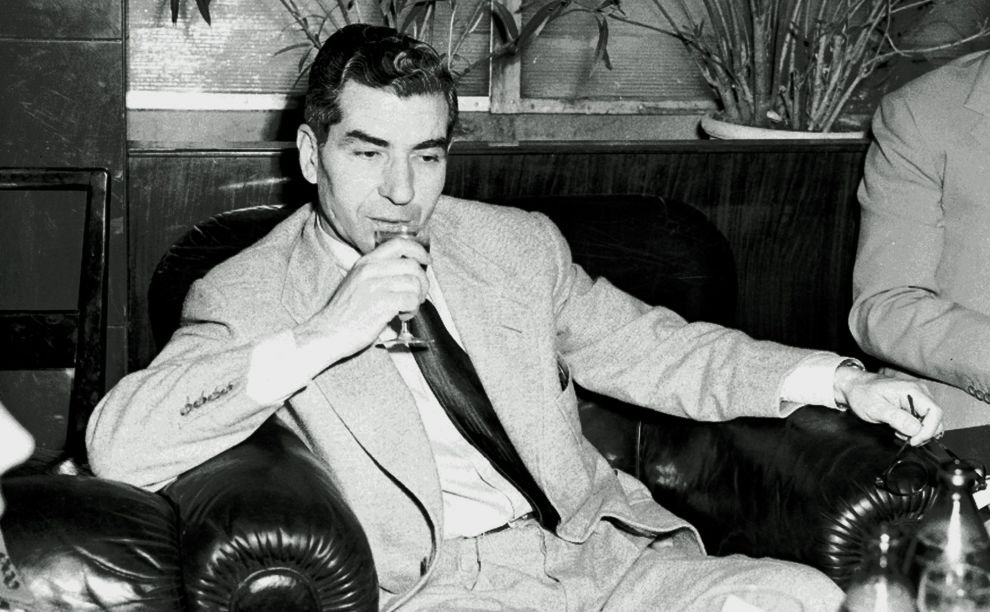

Charles Lucky Luciano (Excelsior Hotel, Rome)

The Godfather

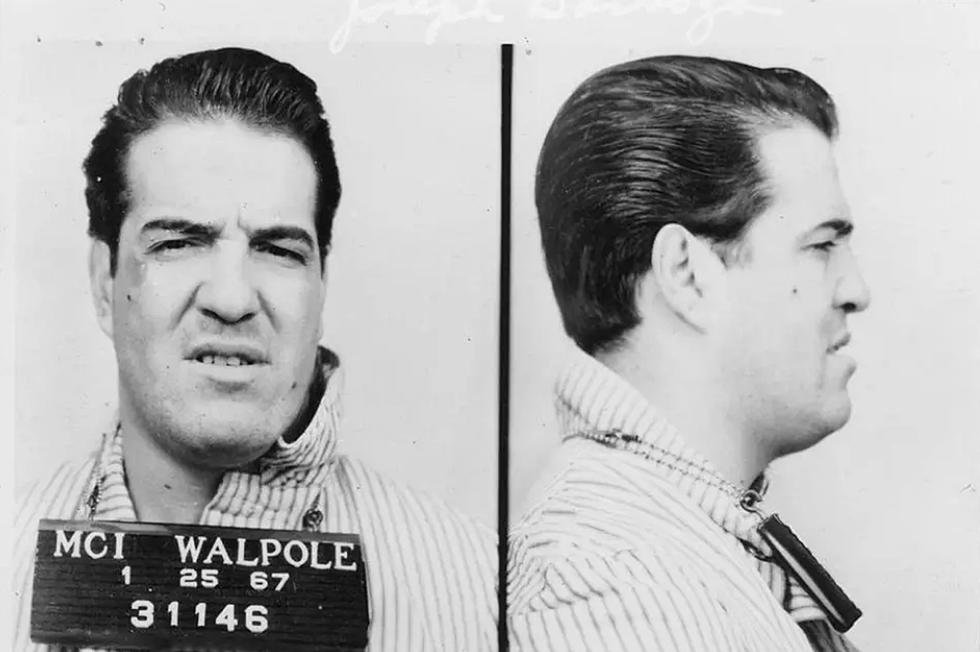

Joe-barboza

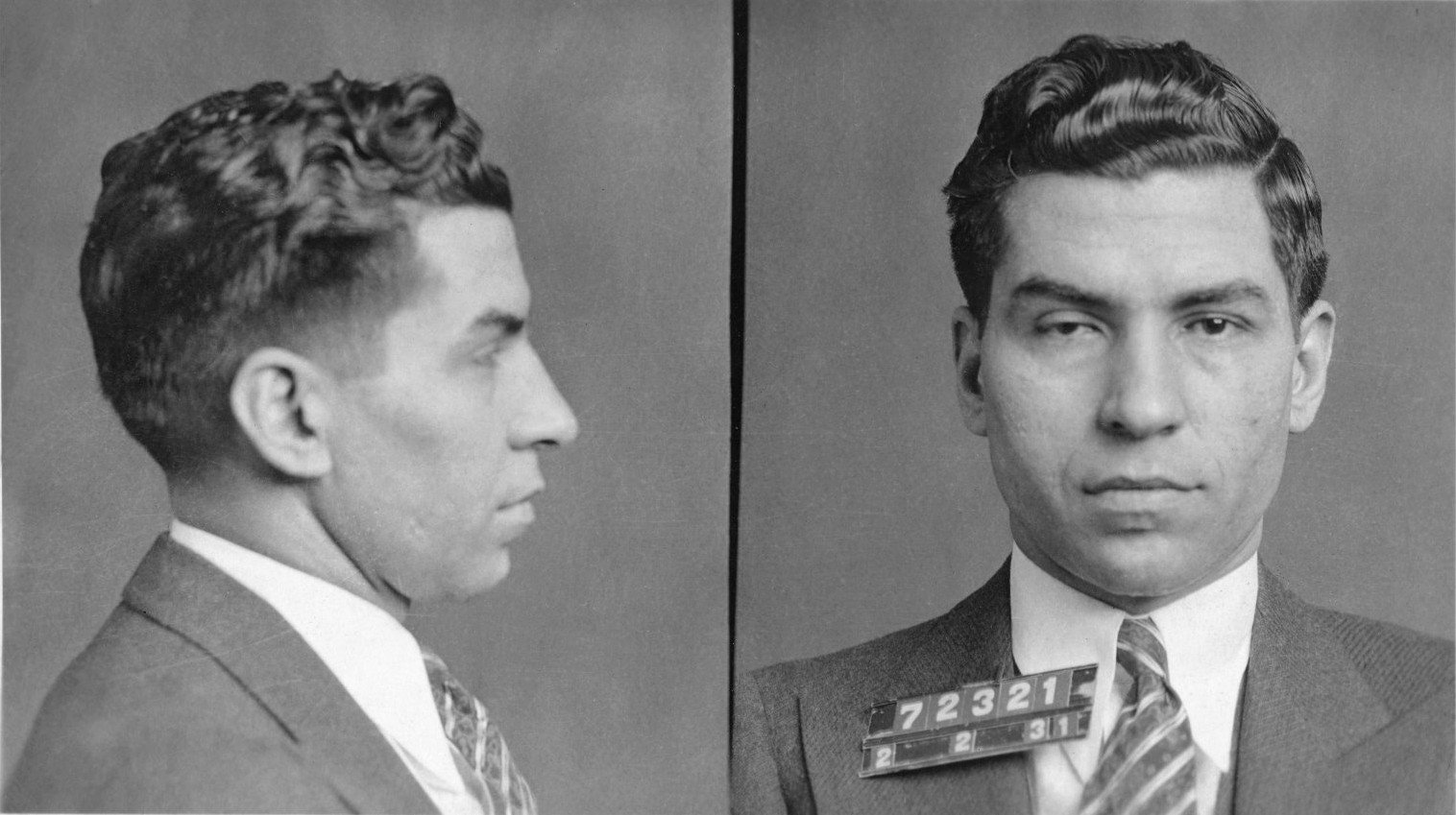

Lucky Luciano

Sources

References/ Additional Reading

How Stuff Works: Witness Protection

AZ Central: Witness Protection Program Who Protects Public

The Mob Museum: Hit Man Sammy Gravano Released

Salon: The mobsters and Terrorists Next Door

Valachi Hearings – Initiation:

Crime Library: Gangsters, outlaws, family epics

UPI Archives: Babysitting Gangsters

Full Script

It starts with a joke. I’m not a practiced joke teller so I won’t deliver it as well as the person I heard it from, but here it is:

A pious man lives his whole life avoiding sin and temptation, dies after a long life, and goes to Heaven. There, God welcomes and embraces him. God says – “What would you like to do, my son?”

The pious man thinks about it, and replies: “Since you asked, God, I’m kind of hungry.”

So God sits the pious man down at a table, and serves him a stalk of celery and a glass of water.

Then God asks, “Is there anything else you’d like?”

The pious man thinks and says, “Well, I’d really like to see some of my friends.”

God replies: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but your friends didn’t make it here, they’re all in Hell.”

This makes the pious man sad. “Is there no way I could visit them?”

God says “Of course, you can visit for awhile.”

“I won’t get trapped there?”

“No, you’ll get to come back, you’ll be fine.”

So the pious man goes down to Hell, where all his best friends are. And they enjoy an incredible meal together – pasta, meat, bread, gallons of good wine. They feast and laugh and have a wonderful time.

The pious man comes back to Heaven, so happy that he got to visit his friends. But, after awhile, he gets hungry again, so he asks God for something to eat.

And, once again, God sits the man down at a table, and brings him a stalk of celery and a glass of water.

Now the man remembers the meal he had in Hell, and he says to God, “I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but don’t people in Heaven get anything else to eat?”

And God answers, “Buddy, do you know how hard it is to cook for just one guy?”

***

Since this is a podcast, I can’t tell if you laughed at the joke or not. But the story of where I heard this joke, and who told it so I could overhear it, turns out to lead down a dark path through the history of organized crime and one of the most revolutionary developments in the history of law enforcement – the Federal Witness Protection Program, the department of the U.S. Marshals service that provides new identities, jobs, and homes to people in exchange for key testimony in federal trials. But where do these witnesses end up? What do they do with their new lives? And had I stumbled into one of the notorious stories of the aftermath of this whole revolutionary program? I’ll tell you the story, and you can decide for yourself.

***

Welcome to My Dark Path. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here. And since friends stay in touch, please reach out to us on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to our creator and host MF Thomas at explore@mydarkpath.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with us. Let’s get started with Episode 25: WITSEC Relocates the Mob.

***

PART ONE

One of the names we have for organized crime emanating from Italian-American communities is “La Cosa Nostra.” The phrase literally just means “This thing of ours.” And that gives us a window into the challenges our justice system faces in battling these organizations. Criminal rackets are built on obfuscation, on people talking in vague language, using code phrases, passing orders through intermediaries to protect the boss from culpability. A prosecutor may be able to prove you told someone “I want you to take care of this thing.” But who can say what thing you’re talking about? Who can say what it means to take care of it?

Although there are organized criminal rackets connected to just about every American community – Russian mobsters, white supremacist gangs, and on and on, it’s “La Cosa Nostra”, the Italian Mafia, that endures in our imagination. Partially this is because some legendary creations of popular culture like “The Godfather” and “The Sopranos”. But in terms of the real-life breadth and power of a mob-like organization, the Mafia can legitimately claim to be in a class by itself.

The history of Mafia activity in America dates back over 150 years, that we know of. And while you might have guessed that it all started in New York, where generations of immigrants arrived on our shores through Ellis Island, the first references we see to mob-like activity committed by Italian immigrants actually comes from over a thousand miles away – in the city of New Orleans. As a major global port, New Orleans is a unique melting pot of cultures, especially from the Caribbean and South America. Many members of old crime families in Sicily had fled to South America to escape justice. Finding their way to America, a young growing nation, they looked for new opportunities to thrive.

There are newspaper accounts in the 1860’s making references to “Black Hand” criminals, or a “Black Hand Society”. If the public knew anything about Italian immigrant gangs, this was probably the first mention of it that they heard. But the term wasn’t accurate – Black Hand wasn’t any kind of organization, it just described a particular kind of crime that was becoming popular. It wasn’t especially sophisticated – a victim would receive an anonymous letter filled with violent threats, demanding that they bring a specified sum of money to a specified place in order to avoid terrible harm coming to themselves and their loved ones. The letter would be punctuated with a drawing of a hand in black ink, held up as a warning. These days, so-called “black hat hackers” commit the modern version of a similar crime – infiltrating your technology and threatening to destroy or publish your personal digital files unless you pay them a ransom.

The intoxicating draw of easy money, the thrill of feeling powerful and unaccountable to the law, it has an addicting effect on certain personality types. As America rapidly expanded towards the west coast, and new cities sprung up from trade, oil money, connections by railroad, it seemed like every major city had its own underworld, along with people savvy and ruthless enough to dominate those underworlds.

Mafia families get up to a lot more than just larceny and extortion. A short list of their money-making enterprises would include crimes like counterfeiting, fencing, illegal gambling, arson, loan sharking, prostitution, weapons trafficking, and murder for hire. If there’s a way to make money and the only obstacle is that it’s illegal, some opportunistic mobster will try it. Henry Hill, the Lucchese mobster turned witness whose story is told in the classic film “Goodfellas”, was involved in point shaving – bribing and intimidating college basketball players to keep their final scores within the point spread established by gamblers. Meanwhile, in the 1980’s, Michael Franzese[ Fraan-zee-see] of the Colombo crime family got the nickname “The Yuppie Don” with a scheme to withhold gasoline taxes from the IRS. He made hundreds of millions of dollars.

And for nearly a century, the American public had no idea just how pervasive the problem had become. There were plenty of pulp novels and movies about criminal gangs, particularly during Prohibition, when entrepreneurial gangsters stepped up to fulfill America’s unquenched appetite for alcohol. But the thought that these groups had established themselves all around the country, that they had enough money to keep police and judges and politicians on their payroll, seemed too fantastical to imagine.

It was during Prohibition that the Mafia became, effectively, a national organization. There was a term that Italian mobsters sometimes used – capo dei capi. It means the boss of bosses. In New York City in February of 1930, a mob war erupted over just who was to be the boss of bosses, the Mafioso that all others would have to pay tribute to.

It’s now known as the Castellammarese War, and in many ways it represented a generational conflict within the Italian-American immigrant community. The older generation still took orders from bosses back in Sicily, and refused to do business with people who weren’t Italian. They were often referred to as “Mustache Petes,” because you could usually identify one by their facial hair. The other side in the war were known as “Young Turks” – Italians who were raised in America, who weren’t obsessed with the old ways of doing business, who were willing to work with non-Italians if there was money in it.

For months, key figures on both sides were murdered, sometimes shot down in the streets in broad daylight. Although the war was ostensibly only happening in New York, criminal organizations as far away as Chicago were pressured to choose sides and provide resources.

It ended after 14 months, when Giuseppe Masseria, also known as “Joe the Boss”, was betrayed and set up for execution by one of his most trusted gunmen, “Lucky” Luciano. They sat down together at a restaurant, Luciano excused himself to go to the restroom, and from there, four assassins gunned down “Joe the Boss”. One of them was Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, the man who later made Las Vegas into a casino empire.

The victor in the war was Salvatore Maranzano; and he had a plan to reduce the conflict between Mafia organizations. He established what are still known today as “The Five Families”, the five dominant Italian-American criminal organizations in New York. His reasoning was that if everyone communicated and respected each others’ territory, there would be fewer bullets flying, and less attention from law enforcement.

Maranzano was obsessed with the Ancient Roman Empire, his nickname was “Caesarico”. And he promoted an organizational structure for the Mafia that was actually based on Julius Caesar’s military chain-of-command. Bosses, consiglieres, underbosses, capos, made men, this system was codified by Caesarico, and it’s still largely followed today.

He might have become one of the most powerful bosses of all time; but his ambition got the better of him. Just months after winning the Castellammarese War, he called a meeting of the heads of the Five Families where he proclaimed himself the new capo dei capi – and said that in exchange for his leadership, he would have the right to take what he pleased from all their enterprises.

His fatal mistake was that he had hired someone with a history of betraying their own boss. “Lucky” Luciano, who had ended the war by turning on one employer, anticipated that Maranzano might consider him a threat, and outmaneuvered him. He hired a group of Jewish gangsters that the Mafia didn’t recognize, and they raided Maranzano’s office, pretending to be government agents. Flashing badges, they disarmed Maranzano’s bodyguards, leaving the self-proclaimed Caesar unprotected. And, just like Ceasar, he was stabbed by many hands at the height of his power. These assassins went a step further, though; after they stabbed him multiple times, they shot him.

Incredibly, his rise to power had been so secretive to the outside world, that the only known photograph of Salvatore Maranzano, the short-lived boss of bosses, was taken at his death.

“Lucky” Luciano refused to promote himself to boss of bosses; he felt like investing that much power in one person was inevitably trouble. Instead he established The Commission, a sort of Board of Directors for the Mafia – the heads of the Five Families plus bosses from Chicago and Buffalo. The job of the Commission was to mediate conflicts – there would always be violent strife in their world, always murder and betrayal, but the Commission was remarkably successful at preventing out-and-out war.

And like I said, all of this happened without the public ever really getting a glimpse at how powerful these organizations had become. Even the head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, refused to devote resources to investigating the idea of an Italian Mob. He was too busy tapping phones and looking for Communists. All of that changed because of one state trooper in a sleepy little town.

***

Edgar D. Croswell worked in Apalachin, a resort community far from New York City. There was one house in particular in this community that fascinated him. It was a large estate owned by Joseph Barbara. His nickname was “Joe the Barber”, and he was the head of the Bufalino Crime Family, which operated in Scranton and other northeastern Pennsylvania towns. Joe the Barber was a bootlegger and a murderer – reports are that he strangled a rival boss to death with his own hands; but now as a thriving boss he had expanded into legitimate businesses. He owned a bottling plant for Canada Dry soft drinks.

Croswell had once stopped a motorist leaving Joe the Barber’s estate, and discovered that the driver had no license, but an extensive criminal record in New York City. So while he had no probable cause to do anything to the rich and powerful man living in the local mansion, he always kept his eyes open. And when he heard that people from the estate were booking a large number of hotel rooms, placing large orders for meat from local butchers, he suspected something was in the works.

On November 14th, 1957, over 100 people converged on Joe the Barber’s estate in Apalachin. It was to be a multi-day meeting of some of the most important bosses in America, and there was a lot on the agenda. Again, the dark parallels to legitimate business are uncanny – think of a major economic summit, a G7 meeting – even though the people at the top are in competition with one another, they can’t resist gathering.

New York State Trooper Edgar Croswell only had to look at Joe the Barber’s driveway, which was suddenly crammed with luxury cars bearing out-of-state license plates. He quietly coordinated a police roadblock; and then law enforcement swooped in and arrested everybody there.

It was the largest mass arrest of the criminal underworld in history; but for the justice system, it was kind of a disaster. After all, there’s nothing illegal about meeting for dinner at somebody’s house. Every charge filed against Mafia bosses in the aftermath of the Apalachin meeting was dropped.

But the real legacy of that night was the publicity that arose from the incredible spectacle. For the first time, America had undeniable evidence that the Mafia was very real.

PART TWO

About a year and a half after the Apalachin incident, a mobster named Joe Valachi was arrested on narcotics charges. He was a veteran in the Mafia world – one of the bodyguards for Salvatore Maranzano before his murder. He ended up in the service of Lucky Luciano’s family, the Genoveses. He was what’s known as a “made man”, meaning he had the blessing and protection of a powerful boss, and that any action taken against him would be answered ruthlessly.

But while he sat behind bars, Valachi began to fear that his boss wanted him dead. He was right, Vito Genovese had placed a bounty on his head. But in a tragic case of mistaken identity, in early 1962, Valachi saw a fellow prisoner and thought he was a family member sent to kill him. He struck first – bludgeoning the prisoner to death with a lead pipe.

Now he wasn’t just doomed to a long time in jail – he was facing the death penalty. And with the bounty still on his head, Genovese had nowhere left to turn, and he did what no one of his stature in the Mafia had ever done – he cooperated with the feds.

I’m going to play you a clip of audio – this is Joe Valachi, in his own voice, giving testimony in a public hearing in front of the U.S. Senate, describing an initiation ritual he went through as part of joining a Mafia family.

This ritual he describes – reciting an oath while tossing a burning wad of paper around in his hands, is part of what the Mafia refers to as “Omerta” – the code of silence. Their most important rule, to never speak of what they do to authorities or outsiders. From the moment someone is welcomed into a Mafia family, this is the message, that the betrayal of Omerta is the greatest sin they could possibly commit.

Getting Joe Valachi in front of microphones, in front of cameras, was not an easy process at all. When President Kennedy was sworn in, he appointed his younger brother, Robert Kennedy, as Attorney General; and the younger Kennedy was determined to take the threat of the Mafia seriously. He created the Organized Crime and Racketeering Division, the first permanent group in the Justice Department dedicated to the fight against organized crime. The biggest challenge he faced was Omerta. Dozens of potential government witnesses had been murdered just in the years since the Apalachin meeting. How could you build a case without someone from the inside who could help you crack the code of how crimes were planned, how orders were given?

Joe Valachi represented an unprecedented opportunity to see behind the curtain – but winning his cooperation was a delicate process. First, he needed to feel secure; the entire top floor of a federal prison was cleared out for him to occupy. It became known as “The Valachi Suite”. His handlers knew that you could soften him up with gifts from the outside – like fine Italian cheeses, or a TV he could watch horse races on. Sometimes, they even put a wig and dark glasses on him, and snuck him out of prison so he could eat at a favorite Italian restaurant.

For over a year, Valachi talked behind the scenes – it wasn’t testimony for any particular case, it was general stuff – observations and life lessons from decades inside the heart of the mob. But Attorney General Kennedy felt like this wasn’t going to be enough – the most impactful thing he could do with Joe Valachi, was to put him in public to tell his story. If he would testify before the Senate, Kennedy promised, Joe Valachi would be transferred to an island in the Pacific with his girlfriend, and left alone to live out his days.

Valachi knew all too well the immensity of his betrayal. Here he is again in that hearing:

The hearings were a national sensation; igniting the fears and imagination of the American public. This was the first public acknowledgment of the true scope and nature of the Mafia, direct from the lips of someone on the inside. This was the first glimpse at the life of a real gangster.

Tragically, the testimony of Joe Valachi was eclipsed by an even bigger story just a month later, when the Attorney General’s brother, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated in Dallas.

***

When Robert Kennedy created the Organized Crime and Racketeering Division, one of his new hires was a young attorney named Gerald Shur. Shur was no stranger to the true power and evil of the Mafia – his father had been a labor organizer on the Upper West Side of New York City; right at the time when New York mobsters were using a stranglehold on trucking to extort local businesses. Dealing with the mob was a dirty, but necessary part of his job – Shur even remember local criminals being invited to his Bar Mitzvah.

Shur had proven himself useful in handling Joe Valachi, in sifting through his testimony in order to produce an overview of the most important insights. And he’d already had painful first-hand experiences with the challenges inherent in developing witnesses – how to get different government agencies to cooperate, how to keep secrets when the Mafia had informants everywhere, how to stop politicians and publicity-seekers from blowing an operation open.

With John F. Kennedy dead, and Robert Kennedy’s tenure as Attorney General coming to an end, many of the most dedicated crimefighters Shur worked with were resigning, or being moved to other assignments. For the new administration, it simply wasn’t as high a priority. Joe Valachi never got his island in the Pacific.

But Shur still believed that this was an important fight; and he had a vision – for a “safe house” program; a formal process for cultivating, and protecting, witnesses to organized crime. He knew that you couldn’t go directly at a boss, but if you could secure a conviction using the testimony of experienced insiders, mid-level people like Valachi, you could topple an entire family.

There wasn’t much appetite for a program like this – government officials didn’t want to reward criminals, bring them gifts, promise them soft treatment. The belief was that you just had to get tough – throw them in a dark hole, give them nothing, demand that they unconditionally spill their guts. The fact that this hadn’t worked for 100 years didn’t sway people; some bad ideas simply never go out of style.

For over two years, Shur struggled to build institutional support, supervising dull but crucial projects like creating a modern database on organized crime figures from all over the country. The government was more willing to fund initiatives like this, and soon local prosecutors in any community learned that you could always call his office and get a thorough report on anyone they had in their sights.

Shur had a key insight – that you could accumulate a lot of influence in government if you were willing to do the boring jobs. By volunteering to do the menial paperwork regarding the processing of potential witnesses, he became the de facto manager of the program. And while he was doing this, a new potential mob witness put the government to its most dangerous test yet.

His name was Joseph Barbazzo – a South Boston contract killer whose nickname was “The Animal”. He had murdered over 20 people for a boss named Patriarca, but now Patriarca had turned on him and tried to kill him. To protect his own life, The Animal was now talking to the FBI.

A young US Mashal named John Partington was put in charge of handling the mass murderer, and preparing him to take the witness stand. There was no playbook for this – Partington had to make it up as he went; and the bounty on Barbazzo’s head was $300,000.

Partington moved The Animal, his family, and his pet German shepherds to a small island used by the Coast Guard in the waters near Rockport, Massachusetts. Over the course of a year, they developed a strange kinship – sometimes Partington would bring his wife with him to talk to Barbazzo’s wife when she got stir crazy. The Animal, Partington discovered, was very determined to see that his daughter kept up with school, and liked to write poetry in his spare time. And yet he had no real regrets about his old profession, no qualms about the lives he’d taken – to him, what he was doing now was self-preservation. And revenge.

He needed the help – Partington got a report that a yacht full of hitmen was headed for their island. He ordered sixteen deputies to line up on the shore, rifles at the ready. After a long, tense staredown, the yacht turned away. Years later, one of the would-be assassins on that yacht became a witness themselves, and Marshal Partington protected him.

When the day came for Joseph Barbazzo to testify against his old boss, no less than five assassins were stationed near the courthouse steps. But they never got a shot at him – Partington had secretly brought him to the courthouse three days before, where they slept on cots in an unidentified room.

With Barbazzo’s testimony, Patriarca was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. This doesn’t seem like much, but it was the first victory ever achieved of someone at his level. It proved that Omerta could be broken, that mob witnesses could be useful in court. An The Animal survived to testify in a dozen more trials – the government needed credibility that they could keep a witness safe. Joseph Barbazzo was the proof they needed.

PART THREE

Joe Valachi never got out of prison, but he worked with a writer to craft a memoir that revealed even more secrets of Mafia life. Gerald Shur frequently met with him in person, and said that, in his final days before dying of testicular cancer, Valachi just wanted to know if he’d done something good for America. Shur believed that, at their core, many of the people they worked with just wanted to feel like they belonged to something; that they had a community, people who cared about them. Some of them were ready and willing to evolve from helping their family, to helping their country.

This wasn’t the case with Joseph Barbazzo. When he parted ways with John Partington, he was headed for San Francisco, with a new name and a job as a cook. But he couldn’t resist the criminal life, and was essentially assassinated.

The government didn’t care as much about that. They liked the positive outcome of taking down a big-time mobster. With the daring, pioneering protective scheme created by John Partington as an example, and Gerald Shur building out his vision of the program from within the Justice Department, The United States Federal Witness Protection Program – WITSEC – was finally a reality.

Not everyone who enters the program is a criminal. If the target of an extortion scheme is brave enough to testify, they may be in enough danger to have to leave their old life behind. And mob witnesses usually wanted their families to come with them, not just for comfort but for their own safety. When you get a new identity, you are forbidden to contact anyone from your former life. It could get both of you killed.

The program is voluntary, and you can lose your protection if you break the rules. You get new documents, a new name, a new life story, a government allowance, an emergency contact number, and a new job in a new town. You won’t have time for long goodbyes with your loved ones. You can spend many anxious weeks isolated in a motel somewhere while your new life is set up. If you make new friends, you do it knowing that if they ever learn the truth about you, it could put their life at risk. And at the first sign of danger, you might have to do it all over again. It’s nothing you would volunteer for normally; but for many people, it’s a life-saving option.

The program quickly picked up steam, within a couple of years, one new witness was coming aboard every week; and for the first time, the Mafia was on the defensive, with city bosses getting arrested and convicted on a regular basis. It didn’t always go smoothly – remember, many mobsters had a lifelong habit of taking what they could get and seeing if they could get more. They knew that their testimony was valuable enough that they could test their limits.

One witness set up a high-profile fashion business in San Francisco, and couldn’t resist playing at being a local celebrity. He also couldn’t resist ripping off his investors to support his lavish lifestyle; and when he was caught, he sued the government for failing to provide him an effective alias. Another witness went to England, scammed millions out of the British banking system using his new identity, then lost it all. He called WITSEC and offered to testify against his accomplices in exchange for a bailout.

And there were the smaller, stranger requests. One witness convinced the government to pay for breast implants for his girlfriend. Another wanted false papers for his thoroughbred horse. And there were tragic instances, where witnesses set free to live their new lives went on violent sprees, costing innocent lives. By no means was it a perfect program; but a remarkable figure jumped out at me as I read more and more about this: as far as we know, 94-97% of people entering Federal Witness Protection have criminal records. But of the tens of thousands of people given new lives through the program, 82% of them were never convicted of another crime. Just as a point of comparison, only 61% of people released from regular prison go on to be upstanding citizens. By this crucial measure, Witness Protection – where people confess to their past wrongs, atone by helping to clean up the community they hurt, and receive dedicated, personal attention and training in how to live a law-abiding life – is doing a better job of rehabilitating criminals than the ordinary prison system. And, most importantly, no witness who stays in the program and plays by the rules has ever been killed – which is downright miraculous.

For Gerald Shur, the model was so successful, that with the Mafia’s power waning, the government applied the same approach to other organizations – inner-city gangs, the Hell’s Angels, even the Medellin drug cartel. Once, a cartel hitman was caught sneaking into the United States, and Shur’s name was in his notebook.

His final, high-profile assignment was to personally oversee the processing of Sammy “The Bull” Gravano – the underboss of the Gambinos, one of the original Five Families in New York City. He was the highest-ranking member of the Mafia to ever break Omerta and testify; and with his help, the notorious John Gotti went to prison and died there.

Sammy the Bull, unfortunately, proved to be an exception to the power of the program to persuade people to live cleaner lives. He left his protection behind after just one year, having plastic surgery and giving splashy interviews to TV shows and magazines. He relished being famous as the man who took down John Gotti. Then he started running a network of ecstasy dealers in Arizona; and soon found himself back in prison. He served his sentence and, believe it or not, he now has a YouTube show and a podcast. You’ll forgive us if we don’t link to it.

But this detail points at one of the big questions that we haven’t explored yet in this story, one of the biggest challenges you face with a program like WITSEC – where do you put these witnesses so they can start their new lives? America is a big place – so what makes one new home better than another?

Early in the program, they established a ground rule – ask the witness what’s the one place they’ve always wanted to live. That’s the one place you definitely don’t send them – since they’ve probably told others about it. You want it to be far away from their old life, to decrease the chance of running into anyone familiar. You want there to be the chance that they can find a job and a community, where they can send their kids to school.

This would be one of those details that more aggressive witnesses wanted to negotiate over. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to go to either Florida or California. And, once you had safely integrated a witness somewhere, there were practical benefits to putting others nearby. After all, you’d already vetted the community. You already had Marshals nearby, ready to respond to threats quickly instead of being spread too thin around the country.

But it seemed as though there was a danger if the concentration of witnesses in an area became too much. In the late 1970’s, the Marshals had moved over 100 ex-Mafia members to Orange County, California, L.A.’s sunny southern neighbor where Disneyland is. Maybe some of the witnesses wanted to go the Happiest Place on Earth. Regardless, once some of them found old friends in their new neighborhood, they couldn’t resist getting back into the old business. Soon they came to dominate the drug trade in the O.C., and it became a national scandal.

In 1990, Hollywood made a comedy film called “My Blue Heaven”, where Steve Martin plays a New York mobster struggling to adapt to life as a witness in the suburbs. Turns out, it was based on a true story – and one US Marshal says that it’s the most accurate depiction he’s ever seen of how some scammers can’t help but keep scamming.

And although Orange County became the most notorious example, there are stories to this day of other communities out there, places that fit the profile of a good place to hide a criminal trying to turn their life around. Places that are sunny, and quiet, that don’t show up in the news. If you were in a town like that – what signs could you look for?

PART FOUR

Remember when I said that this was a story I may have stumbled into, personally? I’m not going to name the town I was in, that seems inappropriate. I’ll just tell you that I was on a road trip, one of my favorite pastimes; and on this particular day, a friend and I were in the American southwest, in a charming town with a population of just a few thousand people. As we walked down the town’s main street, looking for a good spot for breakfast, I noticed a strange coincidence – that a town this small, in a part of the country most known for Hispanic and Native American communities, had a surprising number of Italian restaurants on its main street. And it didn’t stop there - there were wine tasting rooms advertising Italian cuisine, even cafes and ice cream stands had signs out, boasting about “authentic Italian cappuccinos”. Clearly there was heavy local competition for customers who craved Italian flavors.

But I didn’t jump to any conclusions about that until we sat down in a café and ordered our breakfast. In this café, there was an older gentleman sitting at the bar – he looked like he was in his 60’s or 70’s, with a healthy tan. He was loud, gregarious, totally charming, the kind of guy who makes friends in any room, who will talk the ear off a total stranger with jokes and clowning.

He was the one who told the joke I shared with you at the beginning of the episode; the one about the pious man who finds himself alone in Heaven. He delivered it to a couple of tourists sitting near him, who laughed just like he wanted. He asked the tourists where they were coming from and where they were headed; after they answered, he paused for a moment, maybe for dramatic effect, then said: “I’m not supposed to tell you where I’m from, but I’m from Queens”. And then he guffawed, his biggest laugh yet. I felt sure he had delivered this punchline before.

And suddenly, there it was – the key to decoding the oddity of this little town in the desert that has so many Italian restaurants. Had this man been living a false life here for so long that he no longer feared being discovered by the people he testified against? Or was he among so many of his old friends, dining and having a good time with their new identities, that he just didn’t feel like he was in any kind of danger? I thought about that joke he told, about how Hell had better meals and better company. So many people who enter the WITSEC program describe the dark path it took them down, that the disconnection from their old lives, the anonymity and the dull grind of an honest living, was a kind of Hell. I thought about Joe Valachi – asking to be snuck out of prison just so he could eat at a beloved restaurant. About his need at the end of his life to feel like he belonged to something, that he’d done good for America. Maybe this man in this little café had discovered that, even in Hell, at least he was among friends.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m Nicholas Thurkettle, Senior Story Editor and your guest host for this episode. My Dark Path is created and hosted by MF Thomas, who produces the show with Ashley Whitesides and Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. I prepared this story and our fact-checker is Nicholas Abraham; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history and the paranormal with us.