Episode 44

The Rise & Fall of the Airship Italia

In 1925, Roald Amundsen’s expedition to the North Pole failed and his two planes were force to land on the ice without reaching their destination. His team of six barely to civilization aboard a single, stripped down plane. Amundsen, already a seasoned explorer, decided that he’d never again allow himself to be stuck on the ice. A year later, he successfully reached the North Pole aboard the Airship Norge, alongside American Lincoln Ellsworth and Italian airship designer, Umberto Nobile. Conflict among these men finally broke into the open as the Norge struggled back to civilization, barely surviving a terrible storm over Alaska. Then, in 1928 Nobile set out to reach the North Pole again, this time for the sole honor of his country, aboard an Italian named airship of his design with an Italian crew. But this trip would be beset with trials and horrific events that make the disaster of the Airship Italia one that haunts arctic explorers to this day.

Other My Dark Path episodes you might be interested in

Episode 1

Von Zeppelin & the Airship

To see an airship in the early 1900s was to see the dawn of a new age of technology but the experience also changed how one saw the world and its future.

Watch Von Zeppelin & the Airship on YouTube

Full Script

This is the My Dark Path podcast.

Two years ago, I completed the first script for My Dark Path – detailing the incredible history of the airship and one of it’s most famous inventors, Von Zeppelin. Before I started with the episode, I’d never contemplated that the topic of airships could be as complex and rich as it was. I was incredibly fortunate to work with two people – Nicholas Thurkettle and Alex Bagosy on the episode. That experience reminds me of a basic truth – if you want to have a shot being great at something, surround yourself with people who are smarter, more knowledgeable and harder working than you are. Nicholas and Alex certainly meet that criteria. I’m grateful to them for everything they did to get My Dark Path off the ground. Anything you may like about it can be traced to their influence and its flaws are entirely of my own doing.

Working with Nicholas and Alex, we found stories of disasters and triumphs, squandered fortunes and global media frenzies – all centered around airships. And after releasing that first episode, it was only pride that made me believe I had a good handle on the entire airship story. During my research visit to Moscow in 2021, I found an aerospace museum that unveiled additional stories of innovators and their airships that I’d never read about before. But still, from that first episode, I already had two stories of airship adventures penciled into the episode calendar for 2022 and 2023 – the Airship Italia & the Africa Ship. Both are stories of technology innovation, passion for discovery and the power of human will. And now, as we are in the waning months of 2022, I’m so happy to be able to share one of these stories now.

In the 1920s the world looked north to the final pole left unexplored. Harnessing the power of air travel, in the form of dirigible airships, several crews attempted the journey. While some returned home safely, with their pride intact, others did not. This dark path will tell the stories of both, the successes, and the failures. Today I’m sharing the story of the rise and fall of the Airship Italia and its crew.

It's hard to imagine a time when there wasn’t an obvious choice when it comes to international travel. Every year, millions of people fly using commercial and private aircraft, the culmination of over 100 years of development. But at the end of the 18th century, hot air balloons were taking to the skies and capturing people’s imaginations. A little over one hundred years later, those balloons had transformed into massive airships. Unlike their early counterparts, these ships allowed for controlled air travel over long distances. The airships at this time were the superior form of air travel and really competed only against passenger ships for traveling long distances.

In an increasingly globalized world, people looked to airships as the future of transportation, warfare, and exploration. Soon people would be able to buy a ticket and fly from Europe to the Americas and back in a fraction of the time of a sea voyage. Military forces would be able to fly over their enemies and drop catastrophic bombs. It is safe to say while the early hot air balloon captured the imagination of the dreamers, the airships captured the attention of masses and those who governed them.

One of these dreamers was a man named Roald Amundsen. Born and raised by seafaring shipowners and captains on the southern shores of Norway, Amundsen’s path was clear from an early age. He was not only inspired by his kin, but also by the writings of Sir John Franklin, a royal British Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Amundsen later wrote of Sir John Franklin’s narratives stating that during his early age he, “read them with a fervid fascination which has shaped the whole course of my life”.

In 1906, at the age of 34, Amundsen was the first to navigate a ship and crew through the Northwest passage, a sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Five years later he was the first to lead an expedition across the Antarctic ice to the South Pole. Amundsen, nicknamed by his subordinates as Chief, was a strict captain and not one who accepted dissent. He was also a keen observer of technological advances. He saw innovations in air travel as the means by which he would accomplish his next great triumph; an expedition to the North Pole. This is where our story truly begins, because one can not tell the story of the Airship Italia without including the Airship Norge.

With his next adventure in mind, in 1914, Amundsen became Norway's first licensed civilian pilot. After all, he knew that he would not be able to sail a ship to the North Pole. He then began possibly the most challenging part of his expedition, securing funding. Whether it be a ship, airplane, or airship, this trip would be incredibly expensive. The price of a single plane at that time would have easily added up to well over $100,000, and Amundsen wanted at least 2 of them. His income, generated primarily from lecturing on tours in America, would be insufficient to get his expedition off the ground.

But after 10 years of pitching his expedition to private investors and governments, Amundsen had failed to fund his expedition. As it turns out both private and public institutions had found little value or promise in Amundsen's idea. After all, there was little profit to be found in the Arctic tundra. Even after declaring bankruptcy, Amundsen’s lavish lifestyle continued and creditors knocking at his hotel room door.

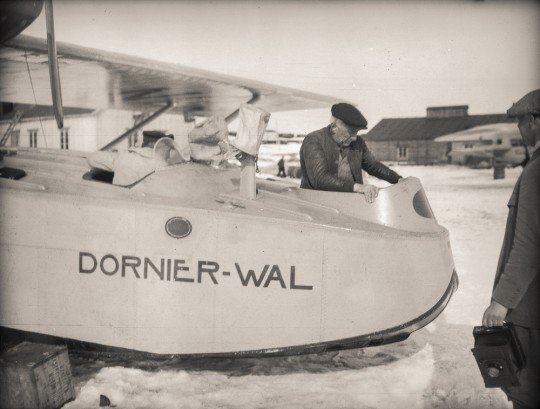

It was at this low time in his life that he was contacted by Lincoln Ellsworth, the son of an American millionaire industrialist. Ellsworth himself was a pilot and engineer, but most importantly, he wanted to bankroll Amundsen’s mission to reach the North Pole. In exchange for joining Amundsen on the trip as a pilot and full partner, Ellsworth provided two planes, the N24 and the N25. These were Dornier Wal flying boats, specially designed for landing and taking off on water. But the planes were small and not designed to traverse long distances, so ironically, the two planes were sent by ship to Norway.

More specifically, they sailed to Kings Bay in a network of islands known both as Svalbard and Spitsbergen. This archipelago was the perfect place to prepare for the expedition as it was located at the midpoint between Norway and the North Pole. It was here that they would establish a base camp and rebuild their aircraft with the help of local coal miners. This is also where they were joined by the other four members of their crew. It would be three men per plane for a 600 mile trip across the Arctic; no small feat. Ellsworth and Amundsen would navigate each plane. The pilots would be Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen and Leif Dietrichson. The third member of each crew would be a mechanic – Oscar Omdal and Karl Feucht.

May 21, 1925 marked their departure date from Kings Bay. The flying boats were designed for water take offs and landings, but they were so over loaded that the crews decided to take off from the icy fjords as a precaution. Aboard the N25 were Riiser-Larsen, Amundsen and Feucht. Omdal, Ellsworth and Dietrichson crewed the N24.

Just after 5pm the planes were in the air, flying north. Amundsen commented, looking down on the bleak ice, “I have never seen anything more desolate and deserted. A bear from time to time…could break the monotony a little. But no – absolutely nothing living.”

After eight hours in the air and with half their fuel used up, Amundsen called for the two planes to land at the earliest safe space in the ice. Somehow, the crews had lost their position and hoped to get oriented once on the ground.

The ice landing on the ice did not go well. First, the planes landed so far from each other that a day passed before the crews could even see the other plane. And it took almost five days before the crew of the N24 could make their way to the N25. It was then the true nature of their situation was clear. The N24 had been irreparably damaged during takeoff and take taken on water during their ice landing. The plane would not make the return trip.

The six man crew was then stranded in the bleak and expansive nothingness of the Arctic sea ice. They had little food. Amundsen later wrote, ““In the utter silence, this seemed to me, to be the kingdom of death”. Amundsen and his crew knew that if they could not fly themselves out that they would die there. Rescue would not have been an option due to the fact that Amundsen was notoriously secretive about his travel plans. He had learned early on that it was the mystery of exploration that captured the imagination of the public and sold newspapers.

When they failed to return to Kings Bay the international community went into a frenzy, stoked by the constant newspaper coverage of the events. There was an international outcry to attempt a rescue.

With no option but to fly out, the crew set out to prepare a crude runway on the ice. The shifting ice forced them to restart their runway several times. Finally, three and half weeks later, they were ready to attempt their escape. They had stripped the N25 of everything but the essentials and even brought extra fuel from the N24. The six of them piled into N25. The makeshift runway proved to be just barely long enough and the N25 struggled into the air. Amundsen must have been both excited about their escape, but sad as he watched as his prize, the North Pole, faded further and further away from him.

Their flight home also ended early. The plane, already low on fuel, was now carrying 3 extra grown adults worth of weight. Eight hours later, the crew was once again required to perform an emergency landing, this time in the frigid ocean waves off the coast of Nordaustlandet Svalbard. Luckily, before long, they were found and rescued by a Norwegian Whaler. As if to confirm how famous the crew had become, the first words out of the Whaler’s mouth when he saw Amundsen was, “you’re supposed to be dead”. Amundsen as it turned out was far from dead, and also far from giving up on his mission.

Hi, I’m MF Thomas, and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science, and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Find us on Instagram, visit mydarkpath.com, and see our videos on YouTube. Next week, I’ll release the newest YouTube episode about the Haunted Taipei Hyatt.

I hope you’ll consider subscribing to My Dark Path Plus on Patreon. For just $5 a month, you’ll have access to an exclusive, subscriber only episode every month. We already have a back catalog of episodes, all about hidden topics of history, science and paranormal from the Soviet era. I’m calling it the Secrets of the Soviets. In fact, just yesterday, I dropped a new episode about the Supressed Soviet UFO Files. And every every few months, subscribers get a free surprise gift like books, tshirts and stickers. Just last month, every Plus subscriber received a copy of my latest novel, Like Clockwork.

But no matter how you choose to connect with me and My Dark Path, I’m grateful for your support.

Let’s begin with Episode 44 The Rise & Fall of the Airship Italia

Part 1

While the Amundsen expedition hadn’t achieved its goals of reaching the north pole or of accomplishing a transpolar flight, they did generate incredible media coverage and public interest. Aboard the salvaged N25, the crew returned to the air on July 5 to fly to Oslo, Norway’s capital. They were welcomed at the palace with a reception and dinner held in their honor. Upwards of 50,000 Norwegian citizens crowded the streets to welcome the returned heroes.

Spending almost 4 weeks on the ice had given Amundsen time to think – and he arrived at two big decisions. The first he refused to ever put himself in a position to be stranded on the ice again. The second was that airplanes would not be the means by which he reached the North Pole.

He shared these decisions with Ellsworth upon their return to civilization. Since airplanes were not the solution, they needed something bigger with far greater fuel capacity.

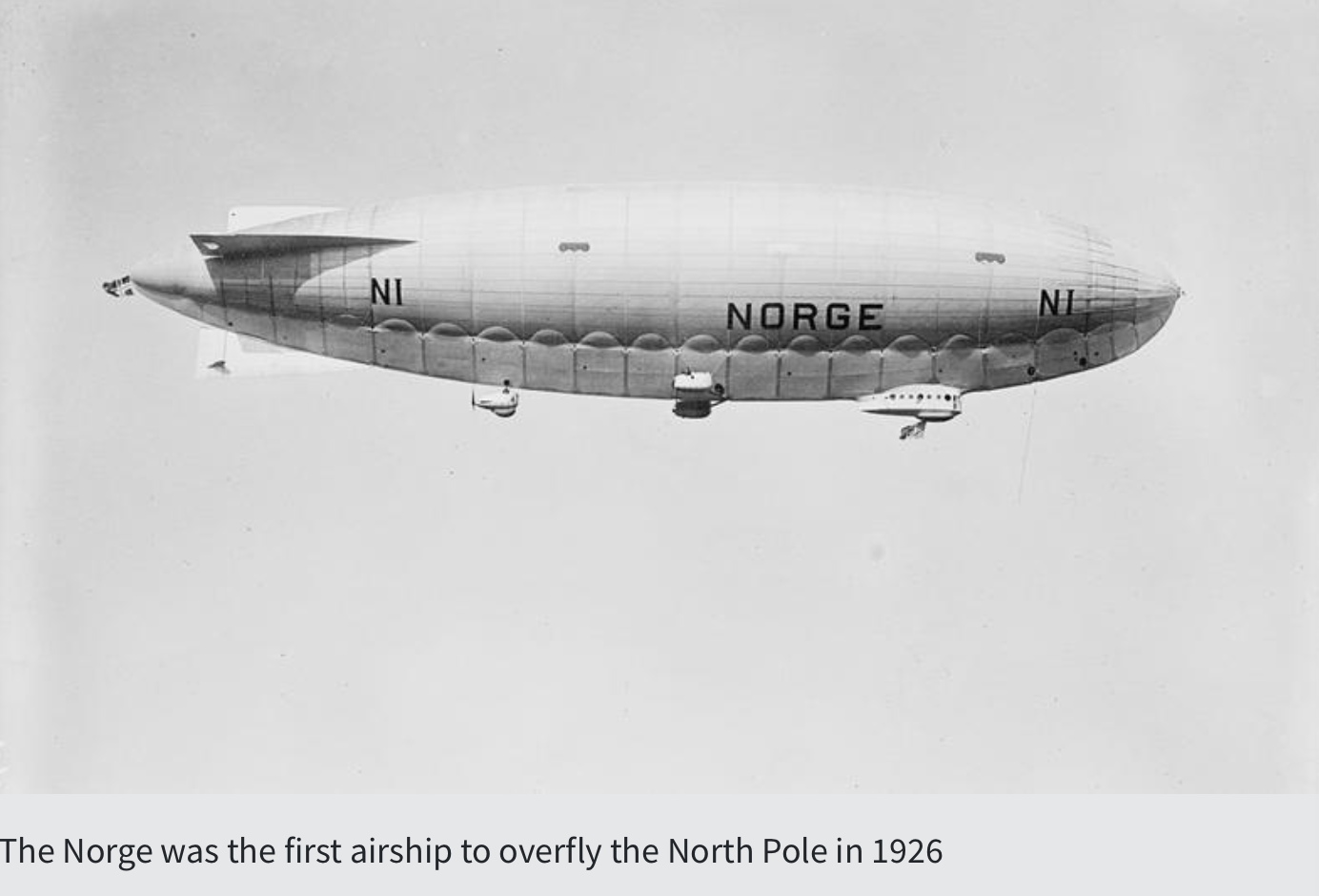

Ellsworth had the answer. He told Amundsen about the N1, an Italian airship that was being sold for an astonishing $100,000 or about 1.5 million dollars in 2022. While the price was exorbitant, Ellsworth had suddenly come into a new source of funding. While the N24 and N25 crews had been clearing a runway on the ice, his father had died in June 1925, leaving him with as massive inheritance.

Amundsen immediately sent a telegraph to the airship's designer, Umberto Nobile. Nobile was already a senior officer in the Italian military air service and was earning a reputation as an airship designer. The N1 would be Nobile’s second airship.

So, less than a month after the failed mission, Amundsen, Ellsworth and Nobile met in Oslo, Norway. Following their meeting Ellsworth agreed to purchase the N1 as well as appoint Nobile its pilot for the next summer’s expedition. It was there that the N1 was named the N1 Norge.

Upon returning to Italy, Umberto Nobile began preparing the Norge. He sent a crew of his engineers to Svalbard. This crew had the unsavory assignment of working through the long and dark winter to build the hangar that would hold the Norge upon its arrival in Norway. While Nobile prepared the N1, Ellsworth and Amundsen focused on a different task. They spent a year stirring up a media frenzy. Almost every newspaper in the world had been printing stories about Amundsen and his expeditions. Now, Amundsen had risen to another level of fame and the newsprint media treated him as such. He and Ellsworth sold the media rights for their coming expedition to news agencies. By the time the summer of 1926 came, the world was collectively on the edge of its seat. This method of fundraising was replicated by other famous airship trips. You may recall from episode 1, Von Zeppelin and the Airship, that LZ-127 would make its famous round the world trip in 1929, partially funded by the Hearst Newspaper corporation.

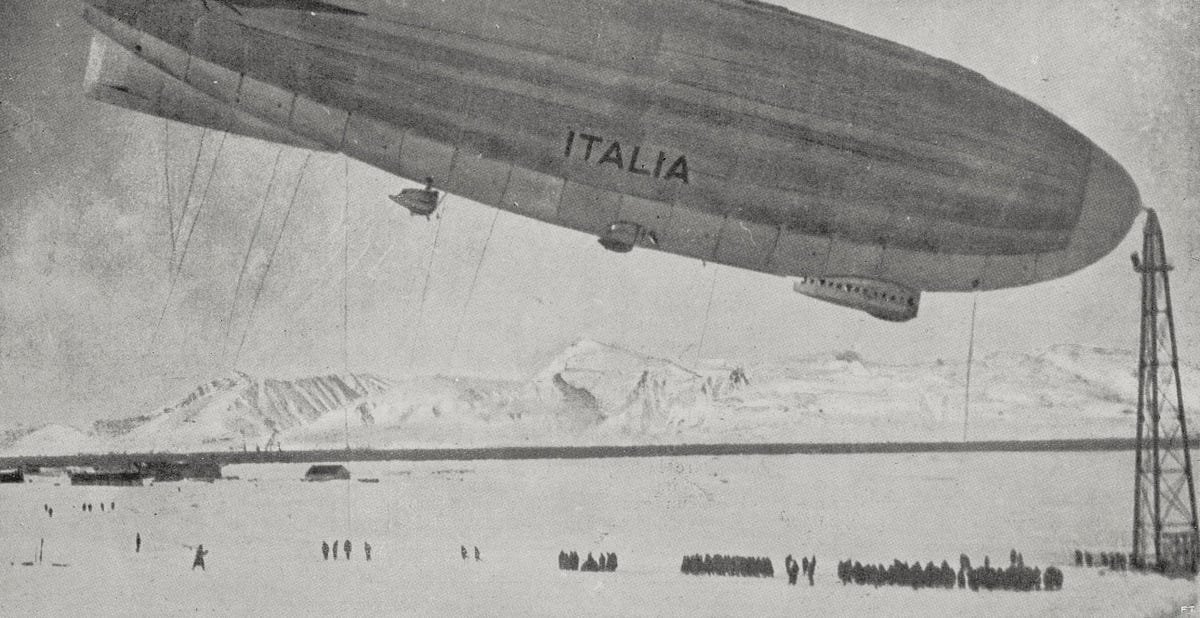

The Airship Norge sailed by boat from Rome to the base camp that had been constructed at Kings Bay on the island of Spitsbergen. It arrived on May 7th, 1926 and was then assembled in the hangar that Nobile’s men had spent the winter building. Four days after the airship's arrival, the crew of 11 and their supplies were ready to start the trip. While the equipment and crew were ready, there were growing problems with the leadership.

A rift had grown between Nobile and Amundsen. This was caused by the fact that Amundsen had only ever wanted Nobile to be a hired hand. While Amundsen was the adventurer-hero in the story, Nobile and Ellsworth clashed over who would be the co-leader. With that said, after the sale of the Airship, Nobile negotiated his way into being full partners with Amundsen and Ellsworth. This forced Amundsen to share the limelight and the glory that he had grown accustomed to. There were also geopolitical elements. Ellsworth discovered that he wasn’t purchasing the N1 from Nobile, as he first believed, from the Italian government. The Italians wanted the expedition to bring glory to Italy but to Mussolini and the ruling Fascist party as well.

By May 11th, Nobile determined that the time of their departure to the north pole had arrived. They planned to leave at 1am, when the air temperature would be the coldest and the Norge would expect the greatest lift from the surrounding air. However, the departure was delayed when Amundsen, Ellsworth and the Norgweigan crew members arrived late.

But finally, the Norge was in the air, planning to cover the 745 mile trip at an expected speed of 50 miles per hour.

The Norge flew, reaching the edge of the ice pack then over the silent, featureless vastness for hours. Some crew continuously walked around the zeppelin, checking for gas leaks. Others monitored the large engines. This was not the luxury that would come to be expected of the intercontinental Zeppelin’s. The crew couldn’t cook because of the risk of fire. The cabin wasn’t heated but at least protected the crew from the wind. Canteens of tea and coffee provided some warmth.

Nobile commanded the flight, collecting and synthesizing information from crew members who piloted and navigated. He was most concerned about the risk of ice buildup, especially when the airship passed through fog. A buildup of ice would add weight but also prevent flaps, valves and other mechanisms from functioning.

But the Norge approached the north pole at 1:30 am on May 12. Because of the time of year, the north pole experiences virtually 24 hours of daylight. The navigator used a sexant to mark the exact position of the north pole and Nobile ordered the engines to be cut, allowing the Norge to float silently about 300 feet from the sea ice. The event, marked another first. Amundsen and another crew member, Oscar Wisting, were the first people to have been to both the north and south poles. Reportedly, they shook hands to commemorate the moment.

Now the power struggle was came fully into the open. Due to dangerous winds, they did not attempt to land the airship. They settled for a flyover with a short ceremony. Amundsen shared some words before dropping a Norwegian flag onto the ice. Ellsworth followed suit with an American flag. Then, Nobile unfurled a much larger Italian flag. This bothered Amundsen incredibly. After all, a large part of the airship’s preparation was carefully calculating and distributing weight. This heavier Italian flag had been snuck aboard and as the captain of the expedition, Amundsen saw it as a direct affront on his leadership. Nobile was now literally and metaphorically casting a shadow over Amundsen’s triumph.

After an hour over the north pole, the engines were restarted and the Norge started it’s return trip to civilization. But now, the destination was Alaska, across an uncharted area where some hoped that new lands would be discovered. After the euphoria of the event, the crew was exhausted and started taking turns sleeping. But at this point, icing beame a real danger. Ice was now forming on the outside of the airship and then breakoff in great sheets or chunks, hitting the engines and risking puncturing a gas envelope. Nobile reduced the speed to reduce the risk of catastrophic damage but ice continued to form, especially at the front or bow of the airship. Ice even destroyed the antenna, cutting off contact with the outside world.

Now the crew, after 4 days of travel, were so exhausted, they were falling asleep on their feet. Soon, the coast of Alaska came into view. But so did a new risk. Winds started buffeting the airship while they attempted to hug the coastline on their way to Nome, Alaska, their destination. To get position reading from their sextant, Nobile steered the Norge above the fog and into the direct sunlight. The heat immediately expanded the hydrogen gas. Valves started to work to vent the gas, but not fast enough. The Norge started to point straight up and rise quickly. The crew responded, albeit with some confusion due to their multiple native languages, shifting forward to rebalance the airship and save the gas envelopes from rupturing from too much pressure. But as they did so, the Norge responded…and the bow pointed to the ground and it now started to plummet. In just two minutes of time, the Norge has risen to 1 miles above sea level then dove to just about 600 feet above the ground. At the same time, the wind blew thim inland. At one point, the Norge came so close to the ground that another antenna was caught on rocks and was violently pulled off the airship. But now stabilized, the Norge continued down the coast.

Once buildings came into view, Nobile, Amundsen and Ellsworth agreed it was time to land, even though they knew they hadn’t reached Nome. But finally, the airship rested on the ground in the town of Teller, about 100 miles from Nome. But they were one final step from safety. Once on the ground, Nobile ordered the gas bags to be partially deflated…dislodging the remaining sheets of ice that had built up on the envelope. Ice and empty gas bags started to collapse, sending the crew racing to the ropes to escape.

The inhabitants of Teller, not expecting their visitors, still greeted the adventurers with cheers of excitement and congratulations. Their arrival was also coupled with a three full page story in the New York Times.

But now, their journey complete, the tension that that remained more or less under the surface, exploded. The article donned Nobile the “new Columbus” and gave him far more credit than Amundsen felt was fair. As if to push his name back to the top of the conversation, Amundsen announced that he was retiring after a long and successful life of exploring. He then returned to Oslo where he could enjoy his retirement and the praise of his peers.

Nobile on the other hand was swimming in glory. He had just been given the, at the time, prestigious title of “new Columbus”. This was a victory for him as an explorer, pilot, and engineer. After all, he was the designer of the Airship Norge. Filled with pride he traveled to New York where he was met outside of Grand Central Station by over 400 Italian members of the Fascist League of North America wearing their infamous black shirts. Their cries of adoration were heard by Mussolini all the way in Italy. By the time Nobile the celebrity returned to Italy, he had not only joined the ranks of Fascism, but had been made a general.

Nobile’s victory tour then brought him all the way to Japan where he was hired to design an airship for their government. His skill in designing, manufacturing and piloting airships was now widely recognized in the eyes of nations who felt airships were the future. There was only one problem, Italy was not one of those nations. During Nobile’s time away from Italy, Mussolini’s right hand man and the Marshal of the Air Force, Italo Balbo, destroyed and melted down one of Nobile’s almost completed airships. As Marshal of the Air Force, Balbo believed that airplanes, not airships, were the way of the future. Tasked with developing Mussolini’s air force, he decided to reclaim some raw materials from the absent Nobile.

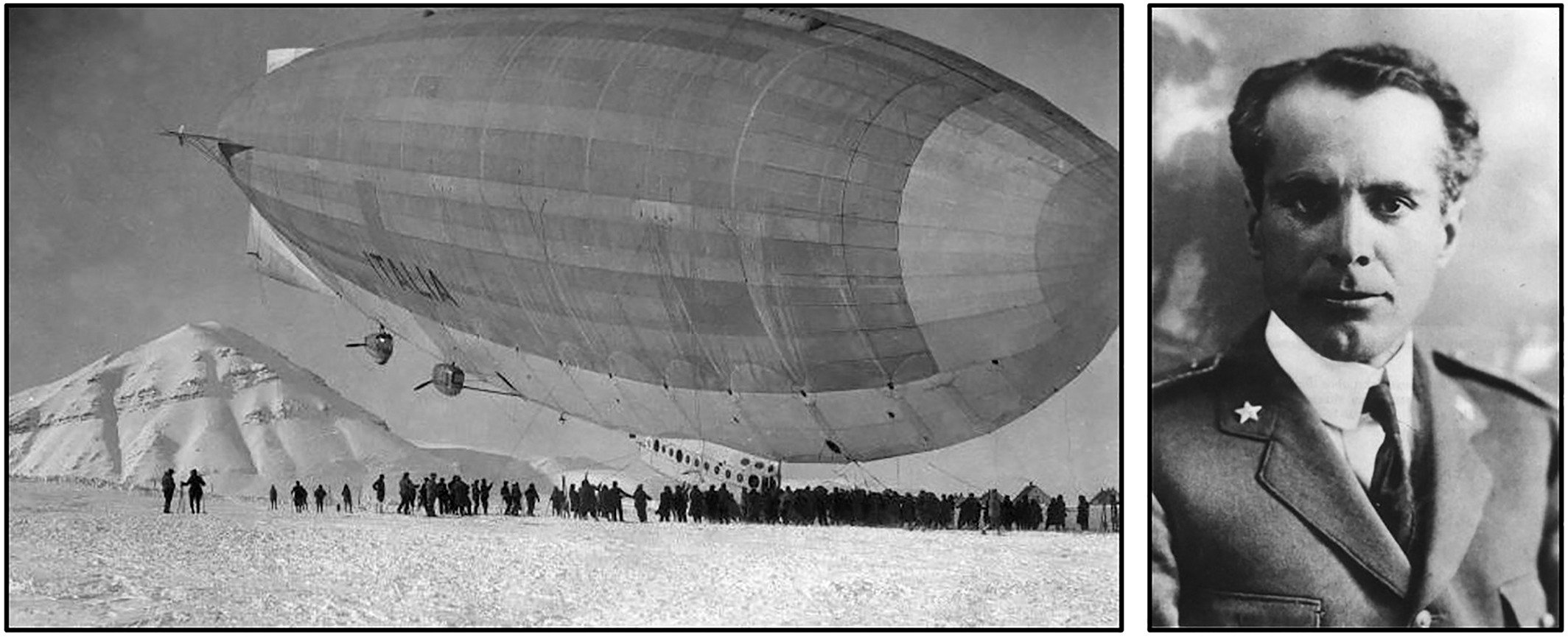

When Nobile heard of this tragedy he began planning another expedition to the North Pole. He felt that his, and Italy’s, triumph had been overshadowed by Norwegians and Americans. He decided that he would return with an (almost) entirely Italian crew to once and for all claim the North Pole for Italy. He returned from Japan with this plan in mind and began to build another airship; The N4 Italia. The Airship Italia was almost identical to the Norge but for its increased fuel capacity. Mussolini and the air force would not support the N4 project, but Nobile secured funding from private backers in Milan.

Mussolini was not a fan of Nobile nor the plan. With that said, he was not blind to the fact that Nobile had become a hero to the people. The Fascist leader felt that it was a bad idea to tempt fate twice. But before he could deny Nobile, he was counseled by Balbo to allow Nobile to pursue his return to the north pole. Balbo famously told Mussolini, “let them go, for he can not possibly come back to bother us anymore”.

With his ship built, Nobile assembled a crew of 15 men who were all Italian save for 1 Swede and 1 Czech. Among them were 3 physicists, a journalist, several navigators, mechanics, and his pet Fox Terrier, Titina. Some crew members, including the Swedish meteorologist Finn Malmgren, were present on both the Norge and Italia. In the days leading up to their departure, Nobile was visited by two world leaders bearing gifts. The first was Mussolini. He carried with him an Italian flag and a promise of a $20,000 bonus to land on the North Pole. That’s about $350,000 today. You might think of this a the Xprize of the 1920s. Nobile was then visited by Pope Pius XI who brought a large oak cross. Within which was a hollowed out section that held a small piece of parchment. It read, in Latin, that the cross was “to be dropped by the leader of the expedition, flying for the second time over the Pole; thus to consecrate the summit of the world”. Before leaving, the Pope told Nobile “Like all crosses, this one will be heavy to carry”.

Part 2

The Airship Italia departed from Milan on April 15th, 1928. Their route would take them over Switzerland and then to Germany. Throughout the 30 hour trip north the fortitude of the Italia was tested. Above Trieste, a city in the Northeast of Italy, one of Airship's tail fins was damaged by strong winds. Fins are fundamental to keeping the airship stable, especially when turning and changing altitude. The crew finally made it to Stolp, Germany on April 16

When they took stock of the situation, the crew realized how lucky they were to have arrived at their first stop. The hail had damaged the propellers and envelope. There was also damage to the tail fin. On top of that they had expended the majority of their fuel in fighting the stormy winds. Repairs were slow to begin because the required parts, and engineers to replace them, needed to come from Italy. The parts and workers arrived in a week and the repairs would end up taking 10 days.

While the team was grounded in Germany, an Australian explorer, Hubert Wilkins, completed a trip from Alaska to Svalbard by airplane. Wilkins was demonstrating the feasibility of using airplanes to explore the Artic. This served as an embarrassment for the immobilized Nobile and his airship. It was made only worse by the following New York Times article that claimed it may be too late for Nobile. It suggested that perhaps the accomplishment of reaching the North Pole had lost its shine and prestige. Nobile would not accept that idea, or failure. With spite and determination as fuel, the crew completed repairs. The crew finally resumed their flight to Svalbard on May 3rd.

The sky was clear and calm as the crew flew over Stockholm, Sweden. So clear in fact that the meteorologist Finn Malmgren, was able to see his family home. Nobile permitted the ship to descend so that Malmgren could drop a letter to his mother. This unusual letter delivery now accomplished, the weather took another turn for the worse. Strong eastward winds continued to push the northward expedition off track. After only one day in the air, Nobile ordered the ship to be moored in Vadsø, Norway. During that time the area was swept with harsh weather conditions including frozen rain and blizzard conditions. While this caused no severe damage to the airship, it continued to fuel Nobile’s feelings of embarrassment. After all, the world was watching as he attempted to prove that airships were the way of the future.

On May 6th, the Italia finally arrived in Kings Bay but there was no time to relax. The Italia was significantly behind schedule and the airship was, once again, in need of repairs. Nobile needed the Italia to be at its best for the final push to the pole. He had shared the glory of being the first to visit the North Pole. But he alone would be the first to widely explore and document it.

Five days after the Italia’s landing in Kings Bay it was back in the air and headed north. The crew was in their positions with Nobile at the helm. The excited energy of adventure was quickly replaced by one of fear and anxiety. Within eight hours of leaving Kings Bay, ice began to form around the envelope of the airship. As it had on the journey of the Norge, this thick layer of ice threatened their safety as it increased the blimps weight and hindered their ability to simply stay in the air. After a long journey filled with dangerous weather and damage to the ship Nobile decided to return to Kings Bay. His first attempt at the North Pole, a failure.

After returning to Kings Bay and again repairing the minor structural damage, the crew again took to the air. On May 15th, Nobile led his crew on a 2,500 mile flight through the uncharted area of the Russian Arctic known, at the time, as Nicholas II Land (Named after the last emperor of Russia). With clear and calm skies, the crew was able to gather significant scientific data. Malmgren was able to record meteorological observations concerning the weather and ice while other members of the crew took measurements of magnetic and radioactive phenomena. This was all done alongside the first geographical mapping of this part of the earth. They then returned to base camp with relative ease. In the end, their second expedition was an absolute success, taking approximately 60 hours.

The luck seemed to continue when they departed on the morning of May 23rd. High above the Greenland coast, a favorable tailwind offered them a boost on their journey north. After 19 hours of flying they arrived at the North Pole. Nobile and the men had prepared equipment to send a team down to the ice but upon their arrival the once favorable wind was now making a ground deployment dangerous. The Italia instead circled the pole while the various scientists in the crew made their observations. With their observations complete, Nobile led a ceremony to commemorate their success.

To mark the moment, the crew gathered in the Gondola and shared words and a drink. They then unpacked the objects that they planned to leave behind on the ice. First would be the flag of Italy and the Flag of Milan. They then dropped a medal depicting the Virgin of the Fire. This pendant was a gift to Nobile from the citizens of a small Italian town named Forli. Finally they dropped the large oak cross bestowed upon Nobile by Pope Pius XI. They then circled the Pole one final time before heading home. As the pole faded into clouds Nobile radioed to the base camp and proclaimed “The flag of Italy again flies above the ice at the Pole''.

The celebration was short-lived. After all, the crew had already been awake for 22 hours. While their trip North had been aided by tail winds, the return trip south was now being hindered by an aggressive headwind of up to thirty miles per hour. Nobile later wrote “Wind and fog. Fog and wind, Incessantly”. Nobile began to worry about their fuel supply as they continued to battle the stormy skies. The worries then shifted focus as a crust of ice began to form around the Airship’s envelope again. Then, about 53 hours into the flight, the imbalance of weight caused the nose to dip, and the airship Italia plunged towards the ice.

Nobile ordered a burst of speed from the engines in order to lift the nose of the ship. When that didn’t work he ordered a halt to all engines. With the engines no longer providing thrust, their descent slowed and stopped just in time. The Italia started to gain altitude, but too quickly. Nobile ordered a release of the gas in order to slow their ascent. At this point he was receiving suggestions from the other crew members in the gondola. One suggested that they continue to rise until they were above the clouds in order to reach sunlight. With the sun they would be able to get an accurate position, recover their sense of direction and navigate home. Nobile accepted this course of action and the airship continued to rise. They remained above the clouds for about 30 minutes.

All was in order once again. They had been able to maintain altitude and find their heading. Nobile ordered the engines to be restarted and they began their descent back into the clouds.

But now…there would be no recovery. Shortly after re entering the clouds the airship began to lose altitude. Unlike before, nothing would halt this descent. Nobile and crew members in the gondola cabin watched through small windows, no doubt in horror and disbelief, as the ice came rushing towards them.

Part 3

What followed can only be described as chaos. The tail of the ship crashed hard causing the cabin to break off from the envelope and then apart. Within the cabin, equipment and bodies flew about, crashing into each other before being thrown out onto the ice. Stunned but alive, they saw the Italia, now without the cabin and any control, still in the air. Aboard where six crew members, clinging to the crippled craft. To their horror, the skeleton of the airship began to drift away, still flying but completely subject to the weather. One of the six still aboard was chief engine mechanic, Ettore Arduino. Heroically, he began throwing boxes of food and survival gear to the ground. He knew, as did the other five, that the wind would carry them away into the frozen artic, to their deaths. The wind continued to blow…and the stricken airship passed from view of the crew on the ice.

Nobile had landed hard on the ice injuring his head and breaking his right arm and right leg. When he opened his eyes he found a number of his men scattered nearby amongst the debris. He awoke just in time to see his beloved Italia adrift and receding into the distance. In this nightmare scenario, it is likely Nobile foresaw his own end, here on the ice. Perhaps, the only question was what would be the cause? Would it be from the cold, from his injuries, or from the looming hunger. But however it might come, Nobile closed his eyes and drifted from consciousness hoping his death would be a swift one. Was it the injury to his head, or the fact that at this point Nobile had been awake for at least 72 hours that dragged his eyelids.

But death did not come for him. He was awoken by other crew members who had fared better during the crash. One man, Felice Trojani, was thrown onto soft snow. He had immediately jumped to his feet unscathed. Natale Cecioni injured both of his legs when he was thrown from the cabin. Alfredo Viglieri and Adalberto Mariano found themselves lying face up, unharmed, among the ship’s debris. Giuseppe Biagi, the ship’s radio operator, had wrapped a portable emergency radio in his arms before being thrown onto the snow. He and the radio both survived. Those who could walk quickly began exploring the wreckage in the hopes of finding their comrades.

In the end, one crew member, Vincenzo Pomella, had died upon impact. There were now 9 survivors on the ice. Biagi set up the radio and began sending SOS messages.

One can hardly imagine the despair felt by these 9 men. Stranded on the arctic ice amongst the howling wind. The same wind that, only moments before, whisked their comrades away. The crew of the Italia was truly lost though not without a bit of luck. The cabin had been stocked and prepared to deploy a team of men down to the ice. And the quick thinking and selfless Arduino had added to their supply of food and equipment. They erected an 8 foot by 8 foot tent to protect from the elements as well as the constant daylight. They then huddled and hoped for sleep.

When they awoke there was the question, what now? The navigators found maps and navigational equipment. They began the task of calculating their position. Biagi continued to send out distress calls with his radio. The rest tended their wounds and took stock of the supplies. The navigators would soon find that the ice pack they landed on was drifting in the wrong direction. Base camp was due south in Svalbard but their calculations suggested that they were headed east towards a remote region of Northern Russia.

By the end of day one, the group was weighing out two options. Nobile figured that the best course of action was to stay put and continue radioing for rescue. Zappi and Mariano, the navigators, believed that they should leave the crash site in order to find land. It would divide the crew, but those who left would be able to possibly send help. Nobile and the other crew members immobilized by injury did not favor this idea. By the end of day two on the ice, no decision had been reached.

The next morning, when Phillipo Zappi exited his tent, he discovered a fully grown polar bear. It was curious, exploring the wreckage dangerously close to the sleeping crew. Zappi whispered as loud as he dared to warn them. Fin Malmgren, the Swedish meteorologist, grabbed the pistol that had been found in the survival pack and snuck out of the tent. The sound of gunshots penetrated the desolate arctic landscape as Malmgren brought down the bear.

Members of the crew awoke startled but were soon relieved by the fact that this bear would now provide the crew with about four hundred pounds of fresh meat. Their fear of starvation was overcome with hope. Their attention returned to the Ondina 33 portable high frequency radio transmitter saved by Biagi. The transmitter was only ever designed for communications between the Italia and explorers deployed onto the ice. Now they needed it to reach the Città de Milano, an Italian Navy ship anchored at King’s Bay. So far they had not received any response or acknowledgment of their distress calls. They were receiving sporadic messages sent by the ship. At this point the Citta de Milano and its Captain, Giuseppe Romagna Manoja had coordinated with Norwegian officials and sent out search parties. It was clear to the crew of the Italia that they would be nowhere close.

Some of the survivors became impatient. The radio clearly wasn’t working and they needed another option. Zappi and Mariano again suggested sending an able-bodied group to search for land and rescue. Nobile, immobilized by his injuries and fading in and out of consciousness, accepted that as an option, unlike the day before when he forbade them. The navigators packed what supplies they could carry, and accompanied by Malmgren began their trudge across the sea ice. Like the six men who disappeared into the clouds with the Italia’s balloon, the three men faded into the harsh artic environment.

But Biagi had not given up. He knew that he needed to reduce the radio’s frequency and extend its range. The only way to do that would be upgrading its antennae. The crew once again searched the wreckage for a metal that could serve them. It was a slow process, but they had plenty of time. For days Biagi and the crew tinkered and experimented with ways to strengthen their radio. The days of distress transmissions unreceived dragged on. They could listen to radio news and even the broadcasting station of Rome, but nothing they sent was ever heard.

That is until June 3rd, their ninth day on the ice. Nicolaj Schmidt, a Russian radio amateur, received the Italia’s SOS. The surviving Italia crew and Nicolaj were not able to maintain a stable connection but they shared coordinates and brief instructions that Nikolaj was able to pass along to Russian authorities. Within a day the crew heard from a news bulletin that their message was received and being relayed to the Italian government. With the Città di Milano already in the area, Mussolini sent 4 additional planes. This was done quietly, after all, a rescue mission was only necessary because of a failed expedition. It is said that Mussolini favored the idea of leaving the men on the ice until he was swayed by one of Nobile’s friends in Milan. Mussolini saw the whole fiasco as a national embarrassment and wanted to keep it quietly under wraps. That, unfortunately for him, would not be the case.

Making contact ignited a frenzy around the world, at least in the countries that cared about such things. It was front page news; the crew of the Italia was stranded somewhere in the Arctic and they needed help. What followed, is still, to this day, the largest search and rescue mission in Arctic history. In total, 23 planes and 20 ships from 7 nations were dispatched. Not only was it the largest, it was also the first polar air and sea rescue ever launched from the Soviet Union, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Italy.

Norway alone contributed 10 ships and 4 aircraft. The airplanes were necessary to locate the men but the exact plan on how to get them off the ice was still in the works. After all, conditions would make landing a plane difficult enough, let alone taking back off. The Soviets took care of that problem by sending 3 powerful ice breaking ships. One of which was captained by Professor Rudolf Samoylovich, an arctic explorer and personal friend of Nobile. Upon hearing the news at a banquet in Oslo, Roald Amundsen, announced to a room full of people that he was ready to join the search. He, along with fellow pilot Lief Dietrichson and a crew of 4, departed from Tomsø on June 18th.

On the ice Nobile and the crew knew help was on the way. They would soon hear the hum of an aircraft passing over their snow covered wreckage. They realized that this may be a problem. During their time on the ice, wind and blizzards had largely covered their camp in snow. Even if the skies were clear it might be possible for a pilot to miss them. With that in mind they covered their tent in red dye found in the wreckage. Biagi continued upgrading their antennae with the hopes of creating a stable outgoing signal. The camp must have been alight with hope and excitement balanced by their sorrow for their nine dead teammates.

On June 22nd after about a month on the ice, the crew heard the familiar hum. Far in the distance, it was still unmistakable as an airplane. In fact, it was one of the four Italian planes surveying the area. The pilot, a man named Maddalena spotted their red tent and began to circle them. While he circled, he recorded footage of the camp, footage that would later be used in newsreels around the world. He then dropped a case of supplies down onto the ice after carefully recording their coordinates. With a wave he set off back to an airstrip to refuel. The case of supplies was all but destroyed when it fell onto the ice but the survivors of the Italia didn’t mind, they had been seen and they would soon be rescued.

Later that day the familiar hum returned when Swedish and Italian planes passed by overhead. The pilots circled and dropped more packages. This time, in addition to well packed supplies, the crew found instructions. The message told the crew to scout for a location that would be sufficient to land a plane fitted with skis instead of pontoons. The crew members who could walk immediately began the search. They quickly discovered a suitable area for a landing strip, free from any large obstructions. They marked it and relayed their findings using the radio.

The next day, Swedish pilot, Einar Lundborg, circled overhead. While other pilots had refused to attempt a landing, Lundborg was confident. He brought the nose of the plane down towards the ice and the crew said a prayer. They watched as he brought his plane down onto the runway, skidding on its newly outfitted skis. But there was no crash. He had landed successfully. Their rescuer was now on the ice with them, and he had a way out. Lundborg stepped from the plane and was met by the elated crew members. Their faces fell slightly when he made it clear that he would only be able to take Nobile. Nobody on the ice was happy about this. The crew wanted out and Nobile refused to abandon them but Lundborg held fast; It was Nobile or nobody.

To this day it is disputed why Lundborg refused to take anybody but Nobile, even as they begged. Was it the glory associated with rescuing a celebrity? Might it have been an order from Mussolini? Some people hold the belief that Lundborg was hired by an insurance company looking to protect itself from the hefty life insurance Nobile had taken out for himself. No matter the reason, the plane only had one seat and Nobile consented. Along with his dog Titina, he climbed into the plane’s cockpit. Lundborg assured the men that he would return shortly before taking off back into the sky.

Lundborg flew Nobile directly to a Swedish base camp where the Citta di Milano was docked. There Nobile was taken in and given medical attention. With the first package secured Lundbrog refueled his plane and, true to his word, headed back in the direction of the crash. When he arrived he circled the crash site again, lining up his landing. He tipped his nose below the horizon and went for it. Unlike before his plane skidded and crashed, immobilizing it. It would seem his first landing was a stroke of luck, and the second showed why the other pilots had been so hesitant to land. Lundborg survived unharmed, adding one more man on the ice in need of rescue.

Lundborg was not the only rescuer who faced peril. During the weeks-long rescue effort, 15 rescuers lost their lives. Included in that number is Roald Amundsen and the 5 other men that he took to the air with. After their first exploration Amundsen and Nobile were far from friends, but it is clear that in the end the two had a hint of respect for one another. After all, it was Nobile who told his rescuers over the radio, “I think you should put yourself entirely in Amundsen’s hands as he is the only expert collaborating with you”. Amundsen unfortunately never made it to Svalbard. He and his airplane full of crew were last seen by a fisherman claiming to see them fly unevenly into a bank of fog. Throughout the summer, rescue parties were dispatched. In the end, all that was ever found of Amundsen’s final flight was a piece of the plane’s pontoon and gas tank floating off of the Norwegian coast.

The crew on the ice didn’t know any of this. All they knew was that the world knew exactly where they were and it was going to continue sending help until they were rescued. They had grown accustomed to waiting which was made only easier by the supply airdrops. On July 12, after nearly 2 more months on the ice, the crew was reached by one of the Soviet icebreakers, the Krassin. The feat of human engineering sliced through the arctic ice and opened a hatch for the men to climb inside. Finally they would be leaving the ice pack, their home for almost the entire polar summer.

When they arrived in the bowels of the ship they were reunited with Zappi and Mariano who had been rescued only a day before. The men looked particularly well nourished for two men stranded on the ice for weeks; they were also missing Malmgren. According to them, Malmgren had collapsed on the ice and urged them to continue without him. This was difficult for the other survivors to believe, not only had Malmgren been one of the fittest of the group, but Zappi was wearing his clothes. The newspapers also found Zappi and Mariano’s story hard to believe. Similar to Arctic exploration, cannibalism was a hot topic in the papers of the time. One newspaper wrote, “Was the Swede eaten by Italians?”.

Nobile, meanwhile, was adamant about joining the search teams still looking for the crew who floated away in the airship's envelope. This was overruled by Mussolini who commanded Nobile to return to Rome. But unlike his previous entrance into the capital, the government and fascist party were not welcoming him back with open arms. In fact, one of the few things that eased Nobile’s return was that he was still regarded by many as a hero to the Italian people. The warmth with which he was welcomed was enough to shake off any remaining arctic chill. Many thousands crowded to welcome him upon his arrival. The warmth quickly ran out when he was confronted by Mussolini. Their first interaction reportedly devolved into a yelling match that nearly turned physical. Nobile’s fight with Mussolini would serve as the final nail in his political coffin. His strong advocacy for airships had garnered him many political enemies in Italy, including Mussolini’s right hand man Balbo.

These political struggles came to fruition when Nobile found himself standing before an Italian Commission of Inquiry. The commission was harshly critical of him on just about every aspect of his command. It was the analysis of an Italian General Crocco, that the Commission leaned on. General Crocco identified that Nobile’s fatal error was continuing to fly the ship into the wind as they left the North Pole. Nobile must have groaned at this. After all, it was the advice of the meteorologist Malmgren that had led him to believe the wind would relent. But such is the burden of command.

In the end the Commission’s conclusions sounded more like personal attacks on Nobile than anything else. They stated that “the expedition lacked an experienced pilot possessing that trained capacity which is to be acquired only by a long course in Navigation… The precise responsibility for the disaster rests on the commander of the Airship Italia for an erroneous maneuver… In all the conduct of the expedition up to the disaster and after, General Nobile has shown himself to have limited technical qualities as a pilot and a negative capacity for command. Nobile would unsuccessfully fight these charges for years before retiring from the Airforce in March of 1929.

The Commission failed to recall his long career of piloting planes and airships as well as his previous journey to the North Pole during which he was the pilot. The commission also refused to take into account that at the time of the crash, Nobile had been awake for at least 72 hours. There was no debate to be had that Nobile and the crew had made mistakes. That being said, these errors were done in a high stakes, and frightening situation, only exacerbated by the mental toll of sleep deprivation. At a certain point without sleep, like the swirling winds of an arctic blizzard, the human mind becomes clouded and incapable of finding solutions to even the most simple problems.

Of the 16 men who embarked on the journey north aboard the Airship Italia eight would survive the crash and summer on the ice. The Italia itself was lost, either on ice or at bottom of the arctic sea with the rest of the lost crew.

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host. This story was prepared by Tyler Brown Ortiz. This is his first project with My Dark Path and I’m delighted to have him on the team. Our creative director is Dom Purdie. I’m thankful for the entire My Dark Path team.

Please give us a rating and review wherever you’re listening. This really helps us grow!

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science, and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.

References & Music

Doomed at the North Pole: Where did the Airship Italia Vanish?

Flying to the North Pole in an Airship Was Easy. Returning Wouldn’t Be So Easy

Crescendo, Featherland

Brenner, Falls

Rites of Passage, Itebloomr

A Most Unusual Discovery, Wicked Cinema

Path of Purpose, Cody Martin

Craft, Shimmer

Images