Plus Episode 2: The Alternative Universe of Soviet Video Games

The history of video games in the Soviet Union follows a very different path than those of the United States & Japan.

Audio is only available to subscribers to My Dark Path Plus

Other My Dark Path Plus episodes you might be interested in

Plus Episode 3:

In Episode 42, I explored how the Soviet government actively supressed the reporting and reserach of UFO reports. But in this Plus episode, I share some of the most famous Soviet UFO cases, including the Soviet Roswell in Dalnegorsk.

Full Script

My Dark Path Plus

Episode 2: The Alternative Universe of Soviet Video Games

This is the My Dark Path podcast with a special “Plus” episode for subscribers.

On my trip to Moscow last year, I packed my itinerary with visits to the destinations we all love—forgotten history, haunted apartment buildings, paranormal research labs—all relics of the brutal period of Soviet domination of Russian life.

I don’t recall what disrupted my schedule, but ultimately a block of time opened in one of my afternoons. I’ve always used Atlas Obscura as a source of potentially interesting destinations, and as I looked at the site for the first time while in Moscow, it showed that I was just a few miles from the Museum of Soviet Arcade Games.

Once I’d made my way there, I was greeted by the alternative universe of Soviet-era arcade machines. The museum displayed dozens of lovingly restored stand-up consoles that, at first glance, resembled those that populated the arcades of my youth. With a stack of kopek coins purchased with my entrance ticket, I approached the consoles, hoping to find a video game that at least resembled one I had some familiarity with . . . so as not to embarrass myself in front of a much more youthful crowd.

Even putting aside the language barrier, the games were fundamentally different from the Pac‑Man, Joust, and Galaga I expected to see . . . at least in a somewhat Sovietized version. And so, what I expected to be a momentary diversion from the intended purpose of my trip turned into a deep dive into how a communist government reconciled itself to the universal human interest in entertainment and diversion.

Hi, I’m MF Thomas, and welcome to the second “Plus” episode of My Dark Path podcast. These are exclusive episodes produced only for subscribers. Thank you for making this show possible with your enthusiasm and support.

I’ve started My Dark Path Plus with a series of episodes focused on the Cold War Soviet Union, which is a rich source of stories you might not have learned about in school. Think of this as a private tour along a dark path I’ve walked during multiple trips to Russia and former Soviet Republics going back many years. This part of the world is rich with stories from the fringes of history, science, and the paranormal. Let’s get underway with My Dark Path Plus, episode 2, “The Alternative Universe of Soviet Video Games.”

PART 1

Picture this: Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev debating the merits of capitalism and communism in an American kitchen. As unlikely as this sounds, the two leaders debated in a model kitchen on July 24, 1959, with the most modern appliances available to US consumers at the time on display around them. The kitchen was part of a US exhibition built in Sokolniki Park in Moscow. Back in 1958, the two countries agreed to set up national exhibitions in the other’s country. The goal of the exhibitions was to create cultural exchanges to develop goodwill among the two countries in either corner of the cold war. The Soviet Union exhibit had just opened in New York a month earlier.

So, the meeting was set for the two leaders, and on a hot afternoon in Moscow, Nixon hosted the Soviet leader Khrushchev to give him a tour of the American exhibition before they opened it to the public. Nixon probably expected the Soviet leader to be thrilled with the exhibit; he was anything but. Maybe it was the heat or the frustration with the technologies he was shown, but Khrushchev’s temper flared during the tour. He showed Nixon and the country what he thought of the display, making his feelings known right in front of a collection of color televisions and scorning the American technology demos.

Khrushchev stated flatly that the Soviet Union was not far behind and would have the same technologies within just a few years. That ruffled the feathers of Nixon, who retorted that the Soviet leader should “not be afraid of ideas. . . . After all, you don’t know everything.” The two went back and forth, with Khrushchev stating, “You know absolutely nothing about communism, except for fear!”

The two leaders continued a debate that was probably best left for a private meeting room. While photographers and reporters watched the escalating argument, they followed them into the kitchen of the model United States home. The model itself seemed to be entirely forgotten as the voices in the room continued to rise. Pointing fingers at each other, the two leaders no longer showed the friendly demeanor they originally intended for the photo op. What was supposed to be an innocent tour of an exhibit turned into a full-blown argument between the two. Nixon brought up Khrushchev’s constant public threats of using nuclear weapons. Nixon stated that threats like that would only bring about a war that no one wanted. Khrushchev was unswayed by Nixon’s reaction and instead continued to threaten him. He stated unequivocally that Nixon’s statement would result in negative consequences. Hurling threats at one another was not how the meeting was supposed to go. At some point, the two leaders realized that their argument was very public, and they started to de-escalate the argument. Nixon stated that he had not been a very good host, and Khrushchev said he just wanted peace between other nations, especially America. Everyone watching the scene unfold probably let out a collective sigh.

But from then on, it was known as the “kitchen debate.” Played out in front of the media, unsurprisingly, it was front-page news in the United States the next day. Since the news wasn’t delivered live on TV and the internet, reports shared both the escalation and the resolution in a single story. While the competition between free markets and communist systems would continue to be debated fiercely over the following decades until the collapse of the USSR, none would occur in such a commonplace location.

Now the American exhibit in Moscow covered 400,000 square feet of So-kol-niki Park, with about 2.7 million people attending it within six weeks. That’s more than double the number of people who visited the Soviet Cultural Exhibit in New York in 1959. Maybe that was part of the frustration that Khrushchev felt during the meeting with Nixon. He might have thought the Soviet exhibit in New York didn’t compare favorably to the US one in Moscow.

The US exhibit in Moscow touched on eleven themes of American life, addressing topics from geography and people to culture and education. Other exhibits focused on areas of scientific research in chemistry, agriculture, medicine, space exploration, and computer science. The computer exhibit was particularly popular, demonstrating an IBM computer that had been converted into a quasi-mechanized diplomat, RAMAC 305. It was a state-of-the-art computer programmed to answer over 3,000 questions about the American dream. People waited in line for over two hours just to ask RAMAC questions, such as “What is the price of American cigarettes?” “What is American rock ‘n’ roll music?” and “What is meant by the American dream?”

There’s no denying that the RAMAC computer was the most popular exhibit, and there’s a reason for that. For the Soviet people, there was a natural curiosity to learn more about the USA, especially because the only information they had access to came from approved Soviet sources.

But RAMAC wasn’t the only American technology that fascinated . . . and alarmed. When observing the model kitchen, Khrushchev thought an electric juice maker was useless. He believed all it took was a couple of drops of lemon juice squeezed into a cup of tea, so why the dramatics required to juice the entire lemon? He wouldn’t admit it, but the exhibit impacted Khrushchev, serving only to amplify his bravado. When he walked through the American car exhibit, he bragged to others on the tour that “we will be making automobiles for America.”

The RAMAC computer reflected a broader Soviet concern. In 1959, very few computers were in use in the Soviet Union; by 1970, only 5,500 computers were operational there. Compare that to the 62,500 computers in use in the United States. Moscow realized they needed to build more computers as quickly as possible. Bureaucrats concluded with their ever-omniscient and ever-wrong wisdom that the only way to accomplish this was to share the burden among their satellite states in the Warsaw Pact. Several member states—notably East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary—had fairly advanced electronics industries whose capabilities in many areas exceeded that of the Soviets, not least because their geographical locations left them relatively less isolated from the West.

At the first conference of the International Center of Scientific and Technical Information in January of 1970, following at least two years of planning and negotiating, the Soviet Union signed an agreement with East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Romania to make the first computer to come out of Eastern Europe based on integrated circuits rather than transistors. The idea of dividing the labor to produce the new computer was taken very literally. In a testimony to the “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” tenet of communism, Poland would make certain ancillary processors, tape readers, and printers; East Germany would make other peripherals; Hungary would make magnetic memories and some systems software; Czechoslovakia would make many of the integrated circuits; Romania and Bulgaria, the weakest sisters in terms of electronics, would make various mechanical and structural odds and ends; and the Soviet Union would design the machines, make the central processors, and be the final authority on the whole project, which was dubbed “Ryad,” a word meaning “row” or “series.” Top-down planning, pervasive fear, and a lack of free-market incentive hurt every element of Soviet society.

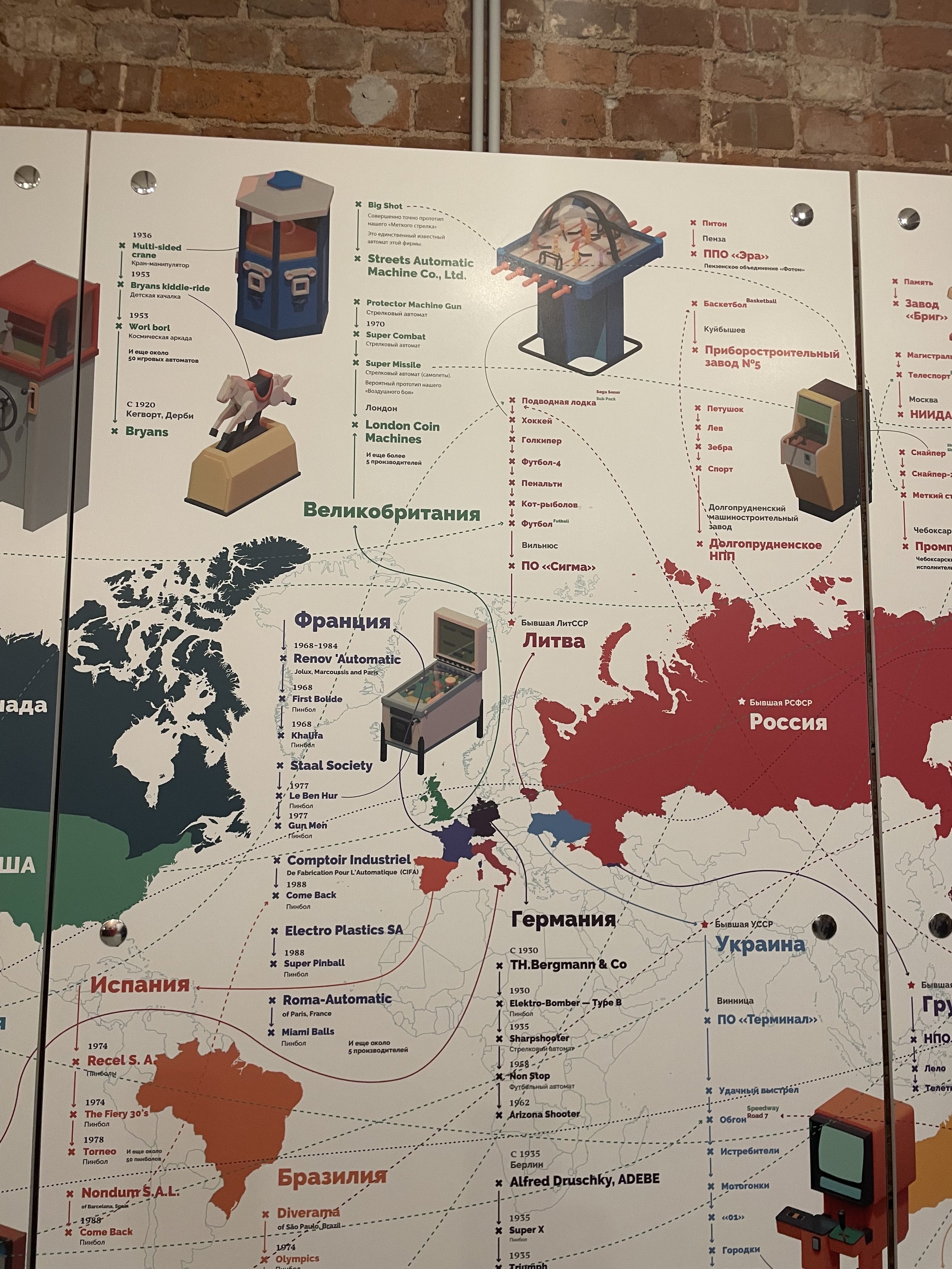

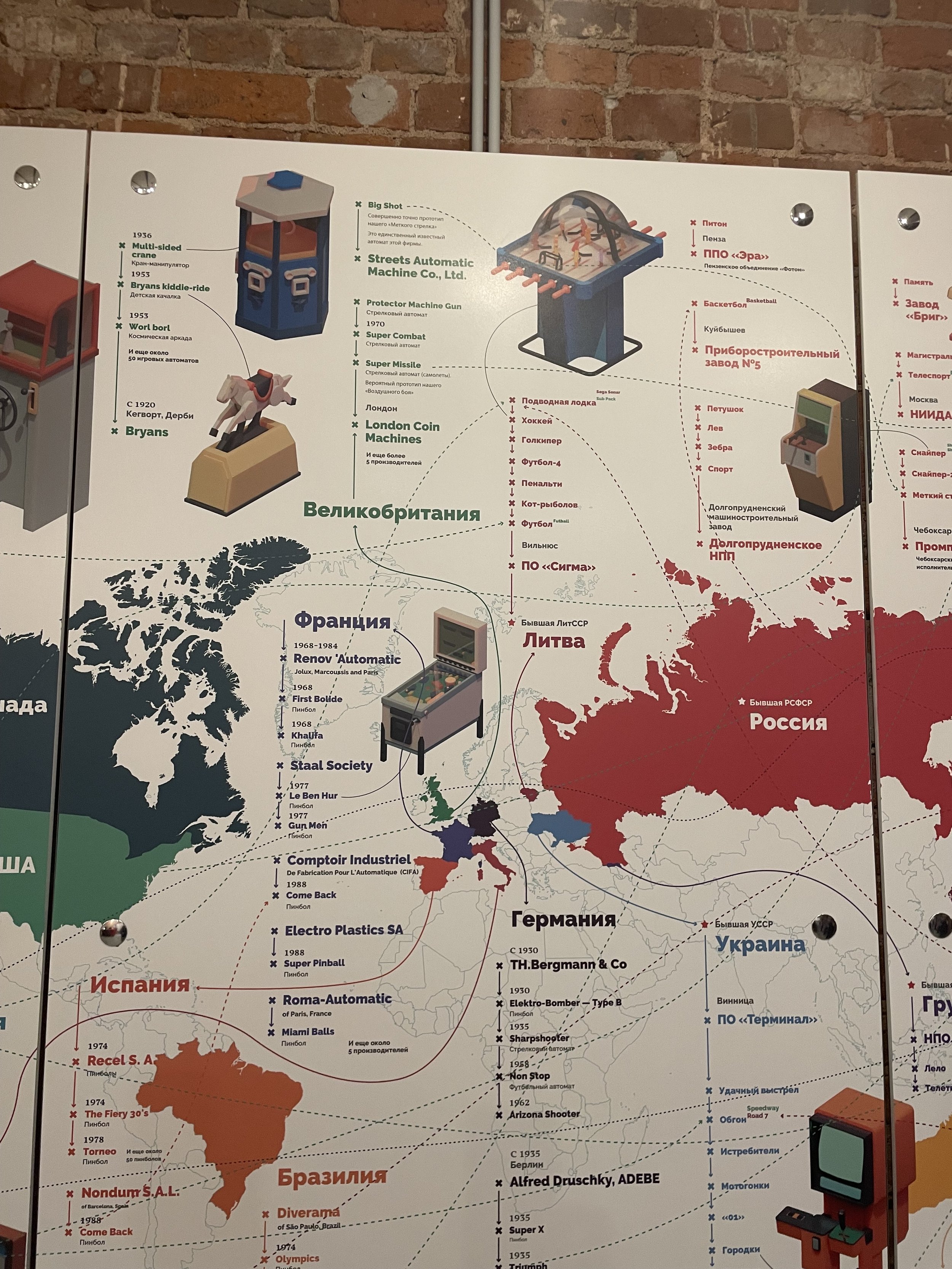

Soviet fear of being left behind in computer science wasn’t limited to computers for military, scientific, and industrial applications. As the kitchen debate revealed, the Soviet government knew that computers had consumer and entertainment applications as well. They’d observed the entertainment industry in the West and Asia explode, especially around video games. And so, to better understand the burgeoning market, they invited the world of arcade machines and entertainment to Moscow by holding the World Amusement and Gaming Exhibition, Attraction‑71, in Gorky and Izmailovsky Parks in 1971. The exhibition featured more than fifty rollercoasters and American arcade machines.

PART 2

What was it that the Soviets were seeing in the US and Japan, in particular? While the Atari console has a foothold in our minds as the icon of early video gaming, the earliest video games actually started in scientific research labs. For example, in 1958, William Higinbotham created Tennis for Two on a large analog computer that used an oscilloscope for a screen as a demonstration for visitors to the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York. In 1962 at MIT, Steve Russell invented one of the most famous pre-Atari games, Spacewar!While the internet wasn’t yet invented, Spacewar! was one of the first games to be played on multiple computer terminals at the same time, controlled by a mainframe computer. Academic staff and those who oversaw these computer labs were not pleased with the perceived waste of time and resources these games represented. Other game developers often had to hide their work to avoid the wrath of professors who viewed this programming as a diversion from the true purpose of their computers.

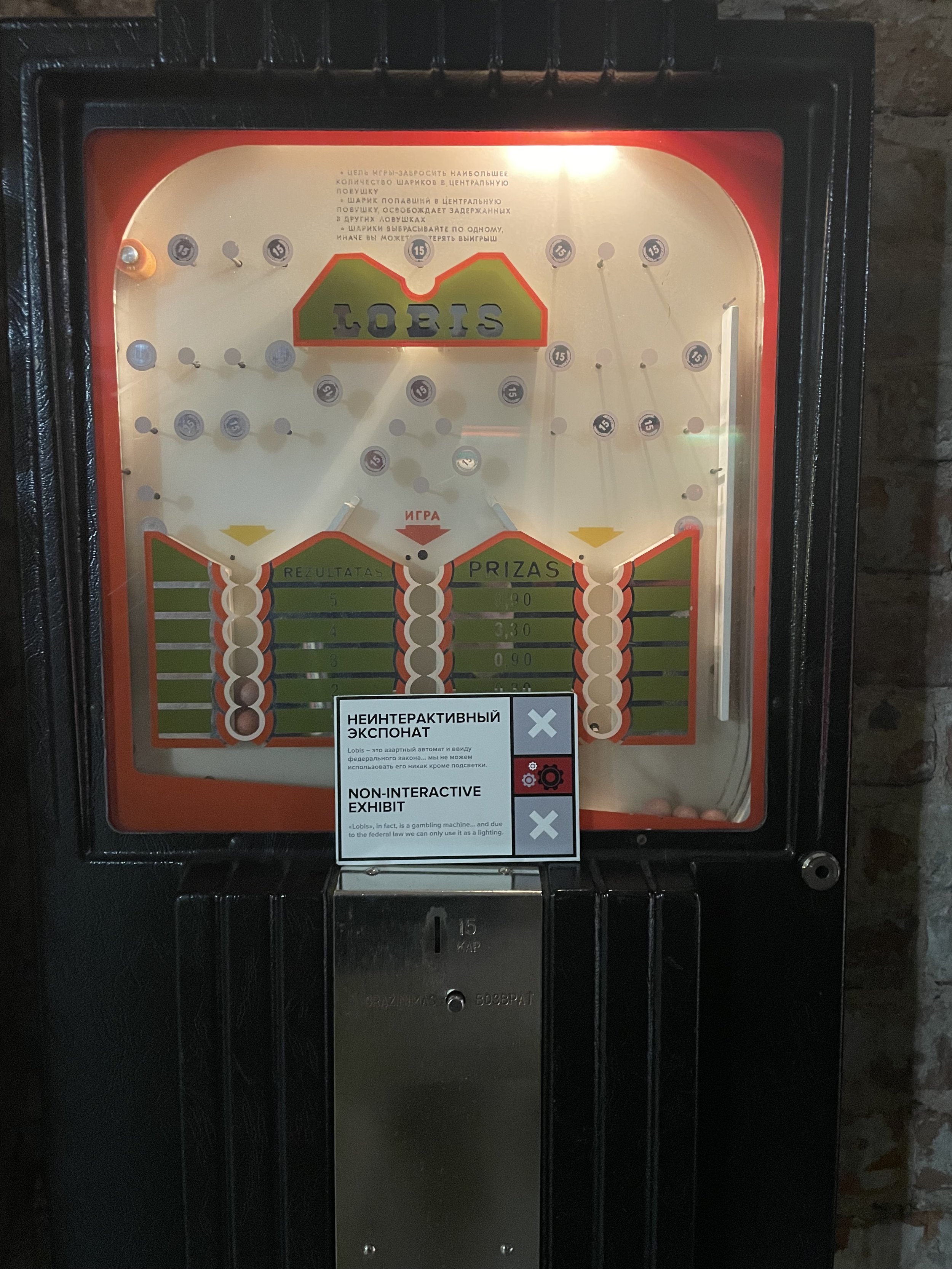

Interestingly, arcades haven’t always been viewed positively or at least neutrally. Pinball machines were introduced in 1933 and the flippers added in 1947, but many states and cities viewed these as games of chance, like gambling, and banned them until the 1960s and 1970s. Arcades evolved in the 1950s as electromechanical games appeared alongside pinball machines. Sega launched Periscope in 1966, establishing arcades as the ideal environment for the launch of video games in the 1970s.

Spacewar! strongly influenced Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, who created Computer Space, often recognized as the first arcade game. This was a coin-operated game, and soon others started appearing in arcades and bars. Alongside these coin-operated games, a home video game industry had also started up. Atari didn’t actually make the first home console; instead, it was a group called Sanders Associates, led by Ralph Baer. Developed in 1967, this device, known as the “Brown Box,” allowed a user to play multiple video games and used a television as a monitor. They licensed it to Magnavox, who branded and sold the console as the Odyssey. While it was a commercial failure, one game inspired Atari’s Pong, which it released in 1972.

Al Alcorn, the designer of Pong alongside Bushnell and Dabney, said of the first Pong console: “We put that machine in one of Andy Capp’s Taverns, on top of a barrel, next to a computer space game. We would come by every few days; we had fifty pinball and driving games there. You could tell how well the game was doing by how much money it made. After a week or two at Andy Capp’s, I got a call that the machine stopped working, which wasn’t a surprise; it was just a prototype. I went into Andy Capp’s to fix it, opened up the coin box, and the thing was just filled with quarters. Pong was just a smash success from the get-go in the coin-operated game business.”

It was in this global environment that the Soviet government saw another industry slipping away. So, when arcade and pinball games were front and center at Attraction-71, it was as exciting as RAMAC had been just over a decade earlier. Reportedly, the line outside the exhibition hall was one of the longest in Soviet history. Visitors queued to see 180 different arcade and slot machines brought in from the United States, Japan, and Europe. Soviet Union residents had never seen anything like it, and roughly 2.5 million people visited the exhibition in ten days.

Broadly speaking, the exhibits were an attempt to reorganize and refresh recreation and entertainment parks. It was no easy task introducing arcade games to the Soviet reality. While the exhibit was popular, broadly, the Soviet people were ambivalent about arcade games and shared some of the same concerns people in the West had—namely, that video games were more akin to gambling than innocent entertainment. But the Soviet government went all in, and the Ministry of Culture promoted the idea that arcade games would help develop fine motor skills, reaction speed, and attention span. This created an enormous demand for arcade video games in the USSR.

Four years later, the first Soviet-made video games were released.

PART 3

The Soviet Ministry of Culture created a new organization responsible for producing video games called the Union SoyuzAttraction, which was formed before the World Amusement and Gaming Exhibition, Attraction-71. Like everything in a communist system, they developed the plan in Moscow, and it cascaded down throughout the USSR.

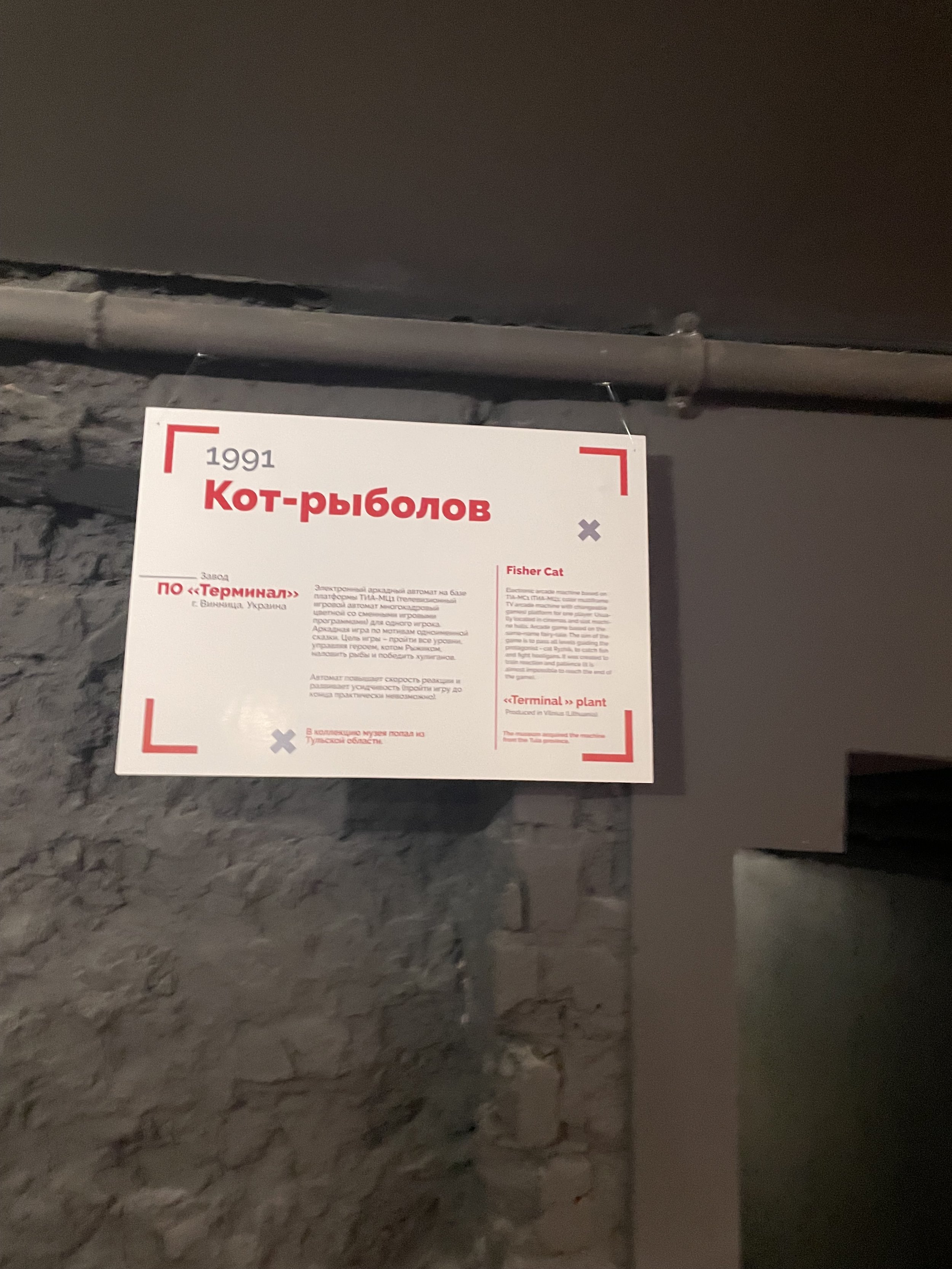

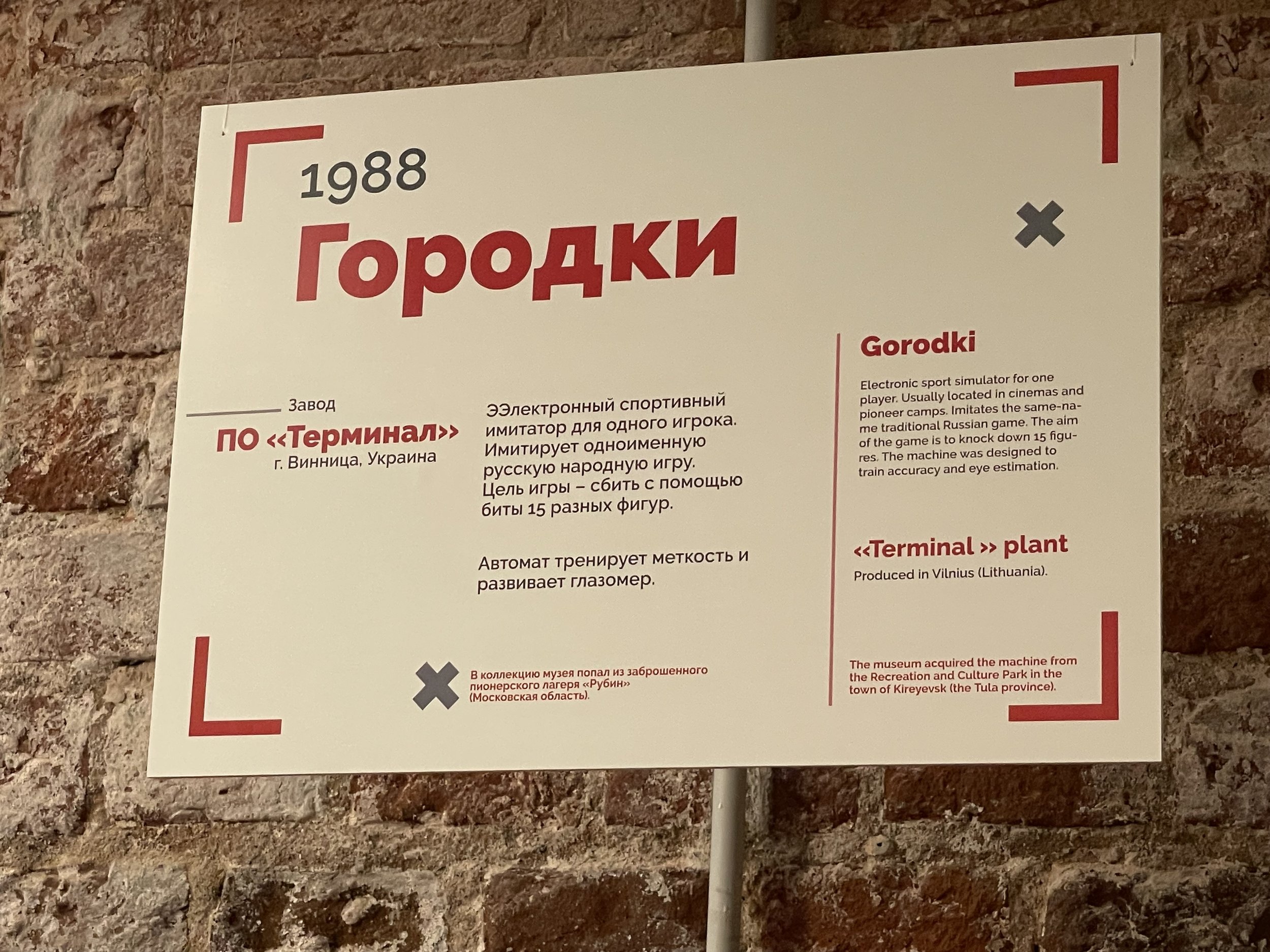

For Soviet-produced video games, two elements were required. First, they needed designs, and second, they needed to be manufactured. Without a game-design culture like in the West, they lacked a ready supply of engineers and designers already creating games on their own. So the Union SoyuzAttraction created a special department charged with designing video games by altering foreign versions. But this department wasn’t just copying games. They were ordered to make the games appropriate for Soviet culture, adapting them to be consistent with the principles of Marxist-Leninist philosophy. This included replacing space aliens and giant gorillas with military-themed games or adding the heroes of Russian folk stories. They also designed games that educated young people about future professions.

Then, for production, the Union SoyuzAttraction turned to the only real manufacturing base in the country—the plants that manufactured military equipment. For example, the Serpukhov Radio Engineering Plant manufactured the video game Sea Battle. Ultimately, the Union SoyuzAttraction commissioned the production of about ninety video games, with manufacturing spread across twenty-two military product factories.

So, as I entered the Moscow Museum of Soviet Arcade Games, about fifty restored games were displayed throughout the space. Virtually every one was restored and being enjoyed by players. I worked my way through a few of them—from hunting enemy naval ships to target shooting. But one, in particular, stood out. I watched players stand on a platform and pull hard on a handle attached to a red bulb, maybe about the size of a beach ball. After the player pulled, the display would show the kilograms of force the player used to pull. The game, as I learned, was called The Turnip and was an example of converting an old Russian folk story into a video game. The story, and therefore the aim of the game, was simple:

An old man planted a turnip. The turnip grew, and grew, and grew some more until it was enormous. The old man tried to pull the turnip out of the ground. He pulled and pulled, but it was just too big for one man alone. So he called his wife to help.

The old woman took hold of the old man, the old man took hold of the turnip, and they pulled and pulled, but they could not pull it out. The turnip was just too big. So the old woman called her granddaughter to help.

The granddaughter took hold of the old woman, the old woman took hold of the old man, the old man took hold of the turnip, and they pulled and pulled. But the turnip was just too big, and they could not pull it out. So the granddaughter called the dog over to help.

Rather than tell the full story, you can imagine how this turns out. Soon, the whole village was engaged in pulling out the enormous turnip . . . a dog taking hold of the granddaughter, a cat taking hold of a dog . . . Unfortunately, this daisy chain of people and animals together could not pull out the giant turnip. That is, until a mouse took hold of the cat, and the whole group pulled on the turnip one last time and finally pulled it from the ground.

The lesson of the folktale was clear and continued to be relevant to Soviet collectivism: that even the smallest and weakest could add value.

As Soviet games slowly made their way from manufacturing plants into Soviet culture, individual machines were available in cinemas, stores, special arcade halls, and pioneer camps, where people could go to play them. Visiting the museum and playing the individual games certainly was interesting. I found it curious that none of the classic Soviet-era games had any global cultural relevance, unlike the games that emerged from the US and Japan in the same period. However, the most popular game to originate in the USSR actually had to escape the iron curtain to create a global following.

PART 4

It was a freezing February day in the 1970s when the teenage Alexey Pajitnov jumped over a huge bank of snow on the street in Moscow. He landed awkwardly and heard his leg snap with “a sickening crack.” He was put in a full leg cast, which forced him to stay at home for several months to heal. To fight the boredom of this home imprisonment, a friend would regularly bring him books of math puzzles.

Alexey, the inventor of the global phenomenon Tetris, would later recognize that this moment would change his life. The teenager became obsessed with these math puzzle books and expanded his interest into other brain teasers. In particular, he became fascinated with something called a pentomino puzzle, a geometric jigsaw that requires the puzzle solver to join pieces made up of five squares into a prescribed area.

If you’ve never played Tetris, it’s still captivating players to this very day. Unlike many other games being designed at the time, Tetris wasn’t fancy at all. There were no frills, fancy images, or interesting characters. There wasn’t even a narrative to the game. The rules were straightforward and simple: You just rotate fast-dropping puzzle pieces in the right spots and watch them disappear. Repeat as you continue to level up.

When Alexey saw a computer at the age of seventeen, he remembered being “spellbound” and would pursue computer science for the rest of his life. After graduating from the Moscow Institute of Aviation, Pajitnov joined the computer department of the Russian Academy of Sciences, where he could use a decade-old computer, the Electronica 60, which had no graphic capability at all. Alexey reported he was “vaguely aware of the growing phenomenon of video games, a major cultural force in the West and Japan.” While the only games approved in the USSR were those we discussed earlier, illicit copies of Pac-Man and others were still around, albeit below the radar. One of Alexey’s co-workers completely reprogrammed Pac-Man from scratch, reportedly to just understand the logic of the programming behind it.

This, too, was a pivotal moment in Alexey’s life as his co-worker’s knockoff of Pac-Man inspired him to recreate the pentomino puzzles on his computer. He coded the first version of the game in just a week. The prototype was functional but not necessarily compelling. But with the help of several colleagues, he made some big updates, including adding color and music to the game, and thus Tetris was born. The name combined the Latin word “tetra” (the numerical prefix “four”) for the four squares of each puzzle piece and “tennis,” Pajitnov’s favorite game.

He then shared the game with his co-workers, who started playing it. What surprised Alexey was that they didn’t stop playing it; they became addicted to the game. These early players would copy the game on their floppy disks and share it with their friends. It wasn’t long before the game quickly spread across Moscow. The New York Post reports that by 1986, everyone with a personal computer in the USSR, although this wasn’t a big number, had played Tetris.

But Alexey couldn’t profit from the demand for the game. The Russian Academy of Sciences had contracted him for ten years, and they owned the game. And distributing video games wasn’t necessarily a priority. Around this time, a computer dealer from the UK was visiting Hungary’s Institute of Computer Science. While in the facility, he saw a group of programmers clustered around a computer terminal . . . all waiting their turn to play Tetris. He played as well and recognized that the game had awesome commercial potential. He tracked down Alexey and offered him a 75% royalty. But the intellectual property was now owned by ELORG, the Soviet organization that controlled the use and licensing of Soviet-created computer software and technologies, led by Nikolai Belikov. Negotiations were settled, at least for the moment, and the game was released with great excitement in the US in 1988. For seven years, Tetris’ reputation and revenue grew—all without Alexey benefiting in the least from his creation. In 1995, the USSR collapsed, and Alexey’s contract with the ELORG expired, allowing Alexey to finally benefit from his creation.

Alexey had been friends with fellow programmer Henk Rogers since the late ’80s. Now, with the freedom to control the future of Tetris, he made an offer to Alexey to form a company together to further develop and distribute Tetris worldwide. Their business exploded, selling over 170 million copies plus another 425 million downloads, generating about $1 billion in sales. Alexey moved to the United States in 1991 with the help of Henk Rogers and still lives in Washington State. Reflecting on his friend and business partner, Rogers commented, “Alexey Pajitnov is perhaps the most famous game designer in the world, yet he’s always been good-natured and philosophical about being denied the profits from his game. After ten years of being left out of Tetris licensing deals arranged by a government that no longer exists, modest Alexey is finally getting his due.”

With those words, let’s return to the story of Al Alcom, the designer of Pong. I’ve not found any record that Al and Alexey ever met in person, but they both reflect the power of freedom, which is ultimately the opportunity to innovate, then to profit or fail. While the nostalgia for Soviet video games is fun to experience, none of them had the power, the stickiness, of what the individual created—in this case, Alexey. And culture is pervasive: it either encourages freedom and innovation, and the opportunity to succeed or fail matters, or it attempts to destroy it.

A simple story about Al Alcom illuminates this. After Pong’s success, Al became the chief engineer at Atari. One day, the front desk called him and said, “We’ve got a hippie kid in the lobby. He says he’s not going to leave until we hire him. Should we call the cops or let him in?”

Intrigued, Alcorn told them to send the young man up to his office. The eighteen-year-old in front of him was slovenly dressed but clearly intelligent and driven. So Alcorn hired him, later describing his decision: “He just walked in the door, and here was an eighteen-year-old kind-of-a-hippy kid, and he wanted a job.” Alcorn asked the young man about where he’d attended school, expecting that perhaps he’d say MIT, Caltech or another engineering school. But the young man gave a name Alcorn didn’t recognize: Reed College. He elaborated that Reed was a literary school, and he’d dropped out. Despite this, Alcorn concluded “But then he started in with this enthusiasm for technology, and he had a spark. He was eighteen years old, so he had to be cheap. And so I hired him!”

And who was that young man? Steve Jobs, iconic visionary and founder of Apple. Freedom to innovate, freedom to succeed or fail, matters.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, the creator and host. I produce the show with our creative director, Dom Purdie. Big thank yous to him and the entire My Dark Path team. Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a rating and review wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you. And stay tuned for xxxx

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science, and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.

-END-

References & Music

References

ReaA Tale of the Mirror World, Part 2: From Mainframes to Micros

Fifty Years Ago, American Exhibition Stunned Soviets in Cold War

Slot machines: Where did they come from in the USSR and how are they arranged?[MH1]

Soviet Computing and Technology Transfer by Seymour E. Goodman

The CIA uses board games to train officers—and I got to play them

The Museum of Soviet Arcade Machines – Why You MUST Visit in Russia!

Model X, Ghost Beatz

Brenner, Falls

Things Stranger Than, Falls

At All Costs, Louis Lion

Slow and Steady, Fairlight

Clear, Fairlight

Images