Episode 19: Colditz Castle - Escaping the Nazis’ Inescapable Prison

These men fought for Britain, France, Poland, and other nations. They were the most daring, imaginative, and brave Allied prisoners plunked into one facility, and for years against all odds and every setback, they relentlessly put the supposedly “escape proof” castle to the test. This is their story – not a single, dramatic mass escape, but a tale of soldiers who wouldn’t let themselves be just prisoners, who kept their fighting spirit alive and never, ever gave up.

Listen to Learn More About:

Listen to Learn More about:

The Fortress Colditz Castle

MI9, the organization designated to help prisoners of war escapes

Failed and successful allied escape attempts like:

Frenchmen drilling escape tunnels down through the clock tower

A British officer sewing themselves into a mattress

A makeshift escape aircraft

Inside Colditz Castle

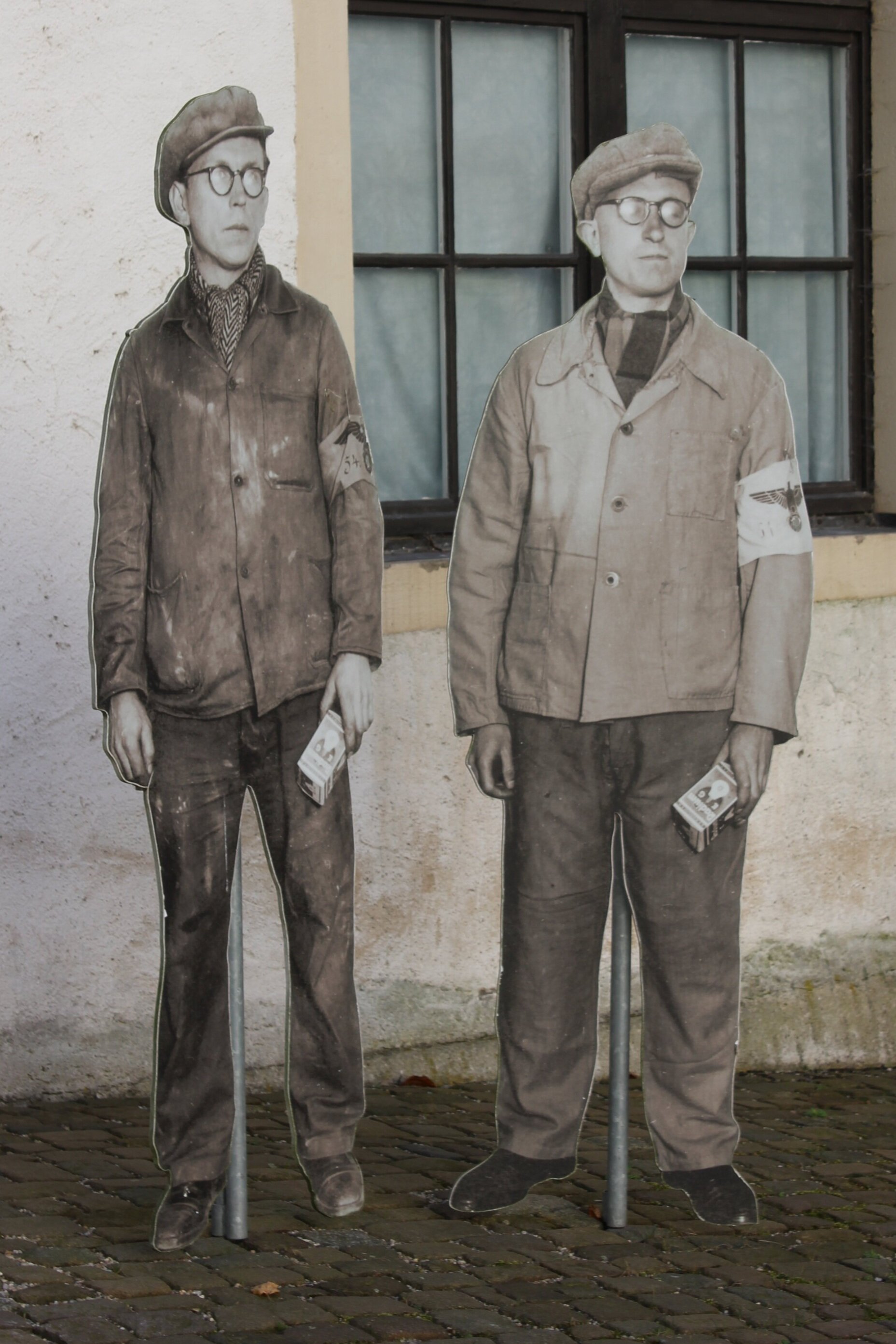

Willi the electrician and his double

Unrenovated Room in Colditz Castle

Image of Colditz from neighboring village

Colditz Castle from afar

Colditz escape tunnel

Reimagined Colidtiz escapee waiting for the train

Colditz Castle

Colditz Castle escape tunnel (2)

Sources

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING/MEDIA:

Channel 4: Escape from Colditz Documentary

Conscript Heroes: Escapers from Germany

MUSIC:

Part 1: Change Will Come by Third Age

Part 2: Camargue by Allice in Winter

Part 4: Romans by Lincoln Davis

White Rabbit: Perfect Spades by Thrid Age and Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES:

Colditz Castle by Lowgoz License

Inside Colditz Castle by Hugh Llewelyn on Flickr License

Colditz Escape Tunnel by Alastair Young on Flickr License

Colditz Escape Tunnel(2) by Alastair Young on Flickr License

View of Colditz Castle from Neighboring Village by Alan Paterson on Flickr License

Unrenovated Room in Colditz Castle by NH53 on Flickr License

Full Script

I want you to picture a castle. We’re in the German free state of Saxony, part of the nation’s south-eastern border. It’s quiet these days, rolling with hills and woven with some of the prettiest rivers you’ll ever see. It’s been inhabited by Germanic people since at least the 1st century BC, but it’s gone through a dizzying 2,000 years’ worth of change. It was part of the Holy Roman Empire, the longtime home for the Slavic culture known as the Sorbs, an independent Kingdom, an ally of Napoleon, a hotbed of revolution and anarchy; and, in its largest city of Dresden, the site of some of the most brutal Allied bombing of the second World War. These days, Dresden is where some of the world’s leading research in electrical bioengineering is taking place, but remnants of all those unstable centuries are never far from view.

Now that castle – castles are built to endure history, aren’t they? And there’s one here which has survived over 800 years of change in Saxony. It’s called Schloss Colditz – Colditz Castle, and major construction on it began in the 12th century, on the orders of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. You can visit it today, it’s just outside of Leipzig, and it now contains both a museum and a youth hostel, if you’re looking for lodging on a budget. It’s been restored to the way it looked just before the outbreak of World War II. So as you tour the grounds, you’ll be able to see what Allied prisoners saw, as they were marched into the walls of a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp.

You see, Colditz Castle was used for many purposes over the centuries. During the Middle Ages it served as a lookout post. In the 1500s it was converted into a menagerie, one of the largest zoos in all of Europe. During the 19th century, it was a workhouse, housing the poor and the ill, before becoming a mental hospital. When the Nazis first came into power, they used it as a political prison for communists and other undesirables. But from roughly 1939 until it was captured by Allied Forces in April of 1945, it was the home of Oflag IV-C.

“Oflag” means “Officer Prison Camp.” You see, Colditz Castle sits atop a steep set of cliffs. The Mulde river flows at the foot of the cliffs and through the surrounding town. It has imposing towers and thick walls, even in our more modern and innocent time, it’s an awesome sight.

What the Nazis saw in these ancient thick walls and high cliffs was a perfect prison. Castles are designed to be impregnable from the outside; but now they intended to reverse the idea. They wanted Oflag IV-C to be escape-proof for the people inside. And they needed the help. Every Allied officer saw it as their duty to attempt to escape, but these particular officers were the biggest trouble-makers in captivity. Every Colditz prisoner was guilty of at least one major escape attempt; many of them had succeeded.

Now, you might be thinking right now of that classic movie, The Great Escape. That film, featuring Steve McQueen’s legendary motorcycle jump, was based on a book about a real mass escape – when 76 prisoners escaped through a tunnel from the supposedly escape-proof Stalag Luft III; only for many of them to be tragically killed. This isn’t that story, but the events of that Great Escape were happening in parallel to the story I’m going to tell you, and had a major impact on the plans of the prisoners at Colditz Castle.

They fought for Britain, France, Poland, and other nations. They were the most daring, imaginative, and brave Allied prisoners plunked into one facility, and for years against all odds and every setback, they relentlessly put the supposedly “escape proof” castle to the test. This is their story – not a single, dramatic mass escape, but a tale of soldiers who wouldn’t let themselves be just prisoners, who kept their fighting spirit alive and never, ever gave up.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 19: Colditz Castle – Escaping the Nazis’ Inescapable Prison.

PART ONE

40 Polish officers arrived at Colditz in November of 1939. They were the first prisoners of this new facility. A year later, they were joined by dozens more prisoners, many of them from the British Royal Air Force – the RAF. No matter what nation they came from, they had one thing in common; the Nazis considered them escape risks. Here, it was believed, escape would be impossible, even for the most notorious escape artists of the war.

They had every reason to be confident. Colditz Castle had an open, medieval courtyard, and walls three meters thick. Outside those walls were battlements 20 meters high, rising out of solid rock. Then there was a double fence of barbed wire, patrolled at all times by armed sentries. And even if you managed to make it beyond all those obstacles, then congratulations, you were now on a sheer cliff 250 feet above the surrounding terrain.

But let’s say you solved all of those problems. Then you had to figure out how to cross 400 miles of enemy territory, all the while knowing that, as soon as you were discovered missing, every town, every train station, and every soldier in the area would be on the lookout for you.

The security officer at Oflag IV-C was Captain Reinhold Eggers. He described his own mission like this:

“The castle was built to be impossible to get into, my job is to make it impossible to get out of.”

***

When a new prisoner arrived at Colditz Castle, the Nazis would tell them, simply and harshly, “for you, the war is over.” Germany, in the beginning, intended to honor the Geneva Conventions for Allied Prisoners of War, and the message they wanted to impress was that you could wait out the war in safety, as long as you didn’t make trouble.

It must have sounded like a tempting argument, but for the officers at Colditz, the war hadn’t ended at all. They just had a new mission. They weren’t in tanks or planes, they were in cramped bunkers with no weapons. They couldn’t liberate European cities or win monumental battles, but they still had a way to fight. In their minds, a soldier who escaped could return to the battlefield. And every Nazi needed to guard over this camp was a Nazi who wasn’t fighting. This was the belief that drove them during their years at Oflag IV-C, and it’s essential to understanding them. They had a duty to try and escape, to harass and confound and distract every Nazi they could, force the enemy to waste precious resources. They had been willing to die in battle before they were captured, and they were willing to risk their lives for this mission now.

To be sure, spirits were low when the officers first arrived. They were cold, dispirited, hungry. The intimidating aura of Colditz Castle worked; it had no obvious weaknesses. But many of the officers who were there remember that the mood changed when they received their first relief packages from the Red Cross. A little bit of food, comfort, and a reminder of home was all the jump start they needed. One officer remembered:

“As soon as we got settled in after Christmas, we started to look around for escaping and means of escape.”

Once they gathered their strength and looked around, the officers at Colditz realized that they had an all-star lineup of escape artists. There was Pat Reid, a civic engineer before the war, whose knowledge of construction and architecture would prove instrumental in multiple attempts. There was Peter Allen, captured at just 20 but a persistent thorn in the side of anyone that tried to keep him captive. And there was Michael Sinclair, one of the war’s most legendary prison escapees – he was born in 1918 into a military family, and in college he extensively studied history and language; he was able to adapt these skills in ingenious ways to benefit all his fellow P.O.W.’s.

Escape wasn’t just a dream for these officers, it was the organizing principle for the entire facility. They established committees, set up an underground economy, and they established a term for what they were after. A successful escape that took a soldier outside of Colditz would be known as a “home run”.

There were individual attempts, group attempts, creative attempts, stupid attempts, boring attempts, crazy attempts, attempts that were made after years of planning and attempts that happened in the spur of the moment. And out of these hundreds of efforts made over the years by these hundreds of captives, there were, depending on who you ask, between 30 and 36 home runs. Today, it’s my privilege to tell you about just a few of them.

PART TWO

The black market at Colditz Castle didn’t just involve materials and supplies. Knowledge had value, and the people who had it, could barter with it. And, incredibly, they weren’t alone. As the war continued, England created MI-9, Military Intelligence 9, a special unit on the home front whose sole purpose was to help Allied prisoners in their escape attempts. Money always helped, you could use it to bribe guards, or to buy provisions for that long trek to the border if you escaped. But their assistance went even further. As soldiers received care packages, they discovered gadgets right out of a James Bond story. Pencil clips could be used as compasses, for example. One prisoner remembered:

“You might get sent a pack of cards, if you dropped them in water the card would peel off, and if you put 52 of them together you got a very good map of Germany.”

And once the officers had one reliable map inside the castle, they found a way to duplicate it, using gelatine as an ad hoc printing press.

Escape committees were formed, and officials elected. The work was too important to be a free-for-all. The committees distributed supplies and money where they thought it would be most useful; they helped with planning, they nominated officers to participate in attempts. They even managed an escape calendar – there were so many attempts in the works at any given moment, and people were always vigilant for spontaneous opportunities, that you needed to keep a calendar to prevent escape plans from stepping on each others’ toes. It was an incredibly effective balance of competition and cooperation; the committee didn’t dictate every activity, they stepped in just enough to make sure everyone’s efforts had the best chance of succeeding.

One of the most striking examples of cooperation and sacrifice had to do with what they called “ghosts”. Remember – any “home run” escape had the extra challenge of that 400-mile trek through enemy territory. And when the Nazis noticed a missing prisoner, an automatic alert would go out to every town and train station between Colditz and the border.

A ghost’s job was to pretend to escape. They would hide somewhere in the castle, tricking the Nazis into sending out the fugitive prisoner alert. For weeks, the ghost had to remain undiscovered, until the Nazis assumed that they had either died or crossed the border. And here’s where the really tricky part would kick in; because at this point, a REAL escape attempt would be made, and if that officer succeeded in getting out, the “ghost” would reappear, and take their place in the headcount at Colditz Castle. If it worked, the Nazis would have no idea that anyone new was missing.

For the “ghost”, this was not only an incredible challenge, it was a major sacrifice. Essentially, their real identity at the prison would be erased – their families would have no idea that they were still there – there would be no more letters, no more care packages. Their relatives would likely conclude that they were dead.

But the officers at Colditz Castle were always able to find officers willing to endure the life of a ghost if it helped the cause.

***

Often, the only thing that separated a failed attempt from a successful attempt was dumb luck. And even the failed attempts directly contributed to knowledge and experience essential for successful attempts that came later.

In this way, the first attempt I want tell you about could be seen as their biggest failure; or maybe, their most valuable learning experience. It took months to plan, and would have been the biggest “home run” in the history of Colditz, if it had worked.

It started in the Spring of 1941. The officers at Colditz were allowed to organize hobbies and activities to keep their spirits up, and the Castle had its own multi-national choir, which performed in the Castle’s chapel. A French Catholic officer who sang in the choir heard a rumor that there was actually a secret crypt below the chapel that might lead to the outside world. When a Castle has stood for as many centuries as Colditz, it can contain far stranger secrets than that. The French officers decided that it was a possibility worth gambling on, and they drew up a plan that could spring as many as 200 of their officers through the crypt.

The biggest obstacle was reaching the crypt at all – the chapel was a busy place for both the captives and the guards, so any destruction of the floor or walls would be noticed quickly. The French would need to tunnel into the crypt from elsewhere in the Castle. Incredibly, their tunnel didn’t start in any basement or cellar. It started at one of the highest points in the castle – the top floor of a clock tower near the chapel. The tower was closed, bricked up, you couldn’t even enter it except through the attic. It never occurred to the Nazis that their prisoners could be digging a tunnel over their heads.

The operation was led by a French Lieutenant named Cazaumayo, who later said: “I think we were mad to start such a job”. Starting from the attic at the top of the clock tower, they dug holes through every floor, all the way down to its foundation. They created a system of pulleys and mattress covers to collect and dispose of all the dirt and broken wood. The attics of other buildings around the compound would serve as the hiding place for all the debris.

They even used the mechanisms of the clock itself in their work – breaking apart gears to make battering rams for the solid rock they encountered underground. They stole lights from around the compound and used old food cans to house them. They would use a rock to cut grooves into an ordinary knife, turning it into a makeshift saw. A single wooden beam could take a whole week to saw through, this was arduous, patient work – but these officers had nothing but time on their hands.

A French priest served as their lookout. If German guards ever got close enough to the clock tower to hear any work, he would kill the lights from above, throwing the workers into a blackout and letting them know to stop work and wait as quietly as they could.

But during the entire process of tunneling down through the clock tower, they were neve caught.

Then, the worst possible discovery – the secret crypt they had heard rumors about, couldn’t be found. Either it didn’t exist, or their tunnel had failed to intersect it. But it won’t surprise you to learn, this didn’t stop the escape artists of Colditz. They determined to keep tunneling right under the walls of the castle if they had to.

While this was going on, a German guard actually stumbled upon some of the dirt and debris in one of the building attics. It must have driven them crazy – they had undeniable evidence that prisoners were tunneling, somewhere, but no matter how thoroughly they searched, they couldn’t discover it. They never thought to look up at the clock tower. And so the French carried on.

They were still working in early 1942, over nine months after the plan was first imagined. The French were just two meters of dirt away from freedom. And then – they were found. The Nazis discovered the tunnel running beneath them, and they surveyed it all the way back to its source. The French prisoners were punished, but perhaps worse than solitary confinement was the loss of that mass escape they’d been dreaming of and laboring towards.

***

Remember when I said that escape attempts were constant, with big plans developing simultaneously with smaller ones. As the French were setting to work on their astonishing tunnel, the British officers had their own plan going which was designed to free a large number of prisoners all at once.

It started with Pat Reid, that officer I mentioned who worked in Civil Engineering back in England. He was known as one of the “Laufen Six” because of the prison he had been in previously – Oflag VII-C at Laufen Castle in Bavaria. He and five fellow prisoners had tunneled out of that castle and nearly made it to Yugoslavia; it was why the Germans wanted him in Colditz. He obsessively studied ducts, drains, and other potential exit points all over the castle. If water could be moved outside the castle walls, he reasoned, there had to be a way to do it with people, too.

He guessed that a drain cover in the prison canteen very likely led outside. They didn’t want to waste this knowledge, so they used a bar of soap and an iron bed leg to make a skeleton key that would let them break into the canteen at night, and explore where the drain led. And before long, they confirmed that Reid was correct; the drain cover could take them outside. But the bad news was that it led directly to a part of the grounds which was always patrolled by an armed guard.

They decided to try simple bribery. Collecting cash from a dozen other officers, Pat Reid managed to collect 500 Reichsmark to convince one guard to look the other way. That would be worth nearly $4,000 today; imagine how much purchasing power that would represent in prison.

On May 29th, 1941, even as the French were in the earliest stages of digging down through the clock tower, Reid and his team started their tight crawl through the drain. They pushed up through the ground, ready to taste freedom. But the guard they had bribed had double-crossed them, and was waiting to turn them in.

The Geneva Convention prohibited the execution of POWs for escape attempts or even during them; so while these British officers knew that they had a long spell in solitary waiting for them, they couldn’t help laughing at their betrayal. The laughter was like a weapon against the Germans, who couldn’t understand how these prisoners could be in such a good mood after a failed escape.

That description of laughter in the face of capture provides so much insight about the mindset of these prisoners. Their goal, their unwavering determination to escape gave the officers at Colditz a purpos, and hope. As long as they held onto that mentality, they would never be merely prisoners.

PART THREE

If large-scale escape attempts were failing, the Allied captives were more than willing to develop and execute smaller-scale plans. In fact, the very first “home run” at Colditz Castle didn’t involve any tunneling, any bribes, or any tools. It was what they called a “snap escape”, one sharp-eyed officer seizing on an unbelievable opportunity.

Alain Le Ray was a French lieutenant, when he was captured he had been married for less than a month. Maybe those home fires burned a little hotter for him; but in Le Ray’s own words, quote: “I wanted to escape as quickly as possible so I could return to the fight.”

Le Ray was being taken on a guarded walk outside the prison compound, when he saw a door left open, in one of the lodging buildings for German junior officers. He didn’t hesitate, he ducked inside the building, laid low for an hour, and then ran. He was out of Colditz Castle.

Now on the loose in the German countryside, he headed south, hopping aboard a German train. He didn’t have tickets, papers, or money, so he dodged from compartment to compartment to avoid being noticed. And, miraculously, it worked. Lt. Alain Le Ray crossed the border into Switzerland. Colditz Castle, the fortress the Nazis considered inescapable, had been escaped; because of one open door, and an incredible blend of daring and old-fashioned luck. Every one of Le Ray’s compatriots was now filled with hope and inspiration.

Around that time, there was another snap escape, this one by that young British officer we mentioned, Peter Allen. He had an unusually small build and, with the help of his comrades, he concealed himself inside an old mattress that was scheduled to be removed from the castle. His fellow officers sewed him inside with 50 Reichsmark and a pair of shorts – he actually planned to take advantage of his small size and disguise himself as a member of the Hitler Youth.

Now this was an immensely risky plan, the Nazis were known to stab at any outgoing rubbish with their bayonets; which would have brought this snap escape to a swift and painful end. But Allen got lucky, and his mattress was removed from the castle without being disturbed. The Germans dumped it in an old barn and, when the coast was clear, Allen freed himself and set out for the border.

Unlike his French counterpart, Peter Allen didn’t hide aboard the train; he used the money he had with him to buy a ticket; going as far towards Vienna as he could afford. He wanted to reach the American consulate and ask for asylum. When his ticket ran out, he just started walking. He was over 200 miles from his destination, and he was on an empty stomach.

Incredibly, Peter Allen dared to start hitchhiking, and thumbed a ride from a car full of SS Officers. His disguise as a Hitler Youth fooled them; and he made it all the way to Vienna. But this was before Pearl Harbor, America hadn’t yet entered the war, and so their consulate refused to grant him sanctuary. He was taken into custody, confessed to being an escaped prisoner, and was shipped back to Colditz, with three weeks in solitary as his reward. He called it the most depressing time of his life; but it wasn’t because he was in solitary; it was because he believed that, by failing to escape, he’d let his fellow officers down.

But the British didn’t have to wait long to score a home run of their own. And it came from the one and only Pat Reid. While he’d been serving a stretch in solitary, he’d carefully observed the buildings he could see from his window, and his engineering brain convinced him that there had to be a useful passageway in one, very special building – the Colditz Castle theatre.

Remember that the prisoners were allowed to engage in hobbies and creative activities to keep up morale, and there was a working theatre company putting on plays and cabarets inside the theater. Pat Reid decided that these players were the perfect people to execute an escape.

Once he left solitary, he cut a hole in the stage floor and there, just as he had guessed, was a tunnel which led outside. But it passed a German guard house, and Reid remembered what had happened the last time they tried to bribe a guard. This time, he put the theatrical skills of his fellow captives to use. They made fake Nazi uniforms using paint that was meant for scenery; they cut fake medals and decorations out of linoleum. It was crude, but on a dark night, they believed it could be good enough.

In January of 1942, two officers – one British, one Dutch – put on their costumes and entered the tunnel. When they emerged, they blended in with the other guards; they were even ordered into the guard room, but the disguises worked. They left the castle, changed into civilian outfits, and caught a train to Switzerland. Another home run.

Now the prisoners were truly inspired; their confidence was growing. 1942 saw what can only be described as a frenzy of attempts; 84 is the best estimate. Many of them failed, but enough of them succeeded – and every attempt was the product of incredible grit, focus, and creative thinking.

In one attempt, a French soldier posed as a German woman, dressed in drag. In another, a former Olympic gymnast scaled down 40 feet of castle wall. One French officer, the prisoners discovered, bore an uncanny resemblance to a German electrician who occasionally came to fix things at the prison. The officers orchestrated a blackout; waited for the electrician to arrive, and then his French doppelganger tried to leave. One soldier managed to reach Switzerland just by hiding in a pile of trash.

And Pat Reid himself, after three failed attempts, escaped Colditz Castle on the night of October 14th, 1942, cutting through the bars on the window of the prison kitchen. He and three other prisoners took a three-day trip to the Swiss border – they slept in the woods, bathed and shaved in a river; at one point, they even spent some time in a local cinema while they waited for a train. He spent the rest of the war in Switzerland, and there’s some indication that while there he worked for MI-6, the British Secret Intelligence Service, debriefing other escaped prisoners. After his service, he returned to his old career of Civil Engineering, and became President of a cricket club.

It was a year-long chess game against the Nazi captors. They started forcing any re-captured prisoners to re-enact their escape attempts on camera, so that the guards could learn what tricks to watch out for. But the Allies always had more tricks up their sleeve.

The stakes, though, got much higher. Remember when I said that officers could be confident they would survive being captured because of the Geneva Convention? By the end of 1942, that all changed. Adolf Hitler declared that any Allied Officer discovered in Germany wearing civilian clothes would be classified as a spy. And spies could be shot.

With the guards at Colditz better trained than ever, and the threat of execution looming over any escape attempt, the frenzy died down. Fewer prisoners made attempts. Perhaps their mission to harass and distract their guards, to return as many officers as possible to the fight, had accomplished all it could.

One man, however, was not willing to give up. Michael Sinclair was a British Officer, infamous amongst the Nazis for having previously escaped 4 different prison camps. In a facility full of the best of the best, he was maybe the most notorious escape artist there. And even under the threat of death, he devised a daring plan to bust out of Colditz Castle – and bring a lot of his comrades with him.

There was a high-ranking German Officer, Fritz Rothenberger, who regularly checked in on Colditz Castle. He bore a strong resemblance to the former Austro-Hungraian Emperor, Franz Josef, so that’s what the prisoners nicknamed him. Franz Josef carried incredible authority with him; the Allied captives could see the fear and obedience he inspired in lower-ranking German soldiers. So Michael Sinclair decided that he could escape, if he could convince just enough Germans that he was Franz Josef.

Like a Method Actor, he studied the Officer Rothenberger, learning every possible detail about his appearance and mannerisms. Taking advantage of the escape industry still operating within the castle walls, he managed the preparation of fake uniforms, fake rifles, fake bayonets, fake medals, fake papers, and more. He believed that he could dismiss the German guards from their posts and march up to 50 Allied officers right out of the castle.

Prisoners watched from the windows on September 2nd, as Michael Sinclair began his performance – maybe the riskiest act of impersonation ever attempted. Incredibly, not one, not two, but three successive sentries believed that the intimidating Fritz Rothernberger himself was ordering them to leave their posts. If Sinclair could bluff just one more guard, he would have his home run.

But the fourth guard saw through the disguise. The alarm was triggered, and in the commotion, Michael Sinclair was shot. His disguise was so effective, that some of the guards believed that they had shot one of their own. But it wasn’t so – Michael Sinclair, the fake Franz Josef, fronting one of the most audacious escape attempts in the history of Colditz Castle, took the bullet. It wasn’t fatal, but it was enough to stop the last large-scale bust-out at Oflag IV-C.

PART FOUR

I’ve saved one of the most amazing stories for the end; it’s not about a home run, or even an attempted escape; rather, this is a plan which never came to fruition. But it’s worth telling in all its incredible detail because it demonstrates how the Allied officers truly never abandoned their mission.

After the shooting of Michael Sinclair, it really seemed like the Nazis had the upper hand. Every hole at Colditz had been plugged. Once again, the prisoners needed to imagine something the Germans wouldn’t, or couldn’t, think of.

One winter day, a prisoner noticed the snowflakes out their window weren’t falling down, they were swirling upwards, pushed by the wind. Remember that the castle sat on top of a cliff, hundreds of feet off the ground, and so it had a distinctive wind pattern. If tunneling below the castle was out, and so was trying bluff, bribe, or sneak your way out of the gates; the only way left, was over. But how could it be done?

Two British officers, Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best, were put in charge of the project. Their ambition, to build a working glider that could be launched from the castle roof, and catapult two prisoners over the walls, the battlements, even the surrounding town, hurtling through the sky towards freedom.

The engineering ambition involved in this blow my mind, especially since no one among the captives had ever done anything like it. They literally based their design on a book about aerodynamics they found in the prison library. They built a fake wall in an attic to hide their workspace, and got to work. They called their glider the Colditz Cock.

The Nazis had an inkling that the British were up to something. They tried to gather intelligence by sending in a double agent to pose as a new prisoner. But the Allies sniffed out his intentions, and the double agent barely escaped being hanged.

Goldfinch and Best scrounged wood from wherever they could – and after several years of escape attempts there wasn’t much to go around. They built a mechanism of pulleys and counterweights that would help launch the glider from the roof. Countless prisoners helped out in any way they could – all this effort and sacrifice and risk, this whole outlandish strategy, just to get two more officers out of the castle, if possible. More than any other story about Oflag IV-C, this underlines for me that for these prisoners, any successful escape was a victory for all of them.

But a horrible piece of news reached them, and put the entire scheme to rest before it could be attempted. At another German prison, Stalag Luft III, 76 prisoners had escaped, using an astoundingly long tunnel and months of preparation. This was the tale that gets told in the movie The Great Escape – of those 76, only three made it all the way to freedom. Most of the rest were rounded up, and massacred by the Nazis.

MI-9, that intelligence branch set up specifically to deal with POW escapes, got word to Colditz Castle – halt any and all escape attempts. The Geneva Conventions had been fully and finally abandoned. And with the British confident that the war was nearing an end, the cost of a failed attempt was just too high. And so the Colditz Cock never flew.

There was only one more attempt to escape Colditz. Michael Sinclair, who had tried and tried and tried again, even surviving a bullet wound while trying to impersonate a Nazi officer, made a final, desperate attempt to bust out. He was gunned down and died on the spot; the only fatality among the hundreds of escape attempts made there over the years.

About his death, one officer said:

“No one has tried harder than he in this war to do his duty. There was no one more loyal. And by his death the regiment has lost a very gallant officer.”

Months after the last escape attempt, in April of 1945, one prisoner noticed “a blob or two” out the window that had not previously been there. Those blobs were, in fact, a line of American tanks. As the tanks approached the castle, the prisoners wrote the letters “P.O.W.” on blankets, and hung them out the windows. As the Americans entered the castle, everyone cheered. At first, the Americans were shocked and confused, until they recognized the cheering men for what they were – Allied officers, exhausted and hungry, but with their spirits intact. Colditz Castle, the pride of the German network of Officers’ Prison Camps, had failed to break them.

***

The prisoners brought their improvised glider down from the attic, and displayed it with pride to their American liberators and fellow prisoners. After the war was over it was burned, no one ever attempted to fly it; it was no longer worth the risk to try.

Some of the former captives would return to the fight. Many others got to finally return home. Some of them returned to Colditz years later, to look at the place where they spent so many months and years, to share their stories to historians and documentarians. Some of the stories I’ve told you come from a documentary produced by Channel 4 in Great Britain, called Escape From Colditz. It’s on YouTube and we’ll link it on our website – trust me, if you’ve enjoyed these tales, it’s worth every minute.

The Nazis were convinced that there would be zero home runs, zero escapes, from Colditz Castle. Instead, the British, French, Polish, Dutch, and other Allied officers masterminded over 30 home runs in the course of the war.

But is that really how we should measure their legacy? I feel like the real great escape was made by everyone there who was a part of the effort. The ghosts, the fabricators, the masterminds, the people who assisted from the outside, the ones who paid for their failures with solitary confinement but shared the lessons of their failures freely – everyone at Colditz worked together to defy the orders of their captors. When the Germans said, “for you, the war is over”, the Officers of Oflag IV-C escaped that edict, and kept up the fight in every way they could, right to the end. The Nazis surrendered before they did. And that’s how a prisoner in an inescapable prison can escape, even if they never get outside the walls.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Ashley Whitesides and Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Sam French. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle and our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy. I’d like to take a moment, on behalf of the whole My Dark Path team, to give special thanks to Alex, who is stepping away from his role on the show as of this episode. He was instrumental in developing My Dark Path from the very beginning – helping to define the high standard of respect for history that everyone here strives for, and fleshing out some of our most compelling stories with his intensive and exacting research. His enthusiasm for this work has inspired all of us; and while others will take up his responsibilities, he truly cannot be replaced. We’re in an ongoing conversation with him about other podcast projects so we’re confident his immense knowledge and talent will be returning to you in some form. Until then, everyone here at the show wishes him the best.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.