The Triumph and Tragedy of the Dole Derby

If I described the flight to Hawaii to someone 100 years ago in 1921, it would indeed sound like magic. At this time, A trip to Hawaii required days on a boat from the West Coast. In 1921, commercial aviation was still in its infancy. The year of 1919 is often marked as the start of the commercial air travel market in the USA. Total passenger trips was measured by the thousands, instead of tens of millions like today.

Before the pandemic shutdowns, Hawaii welcomed over 10 million visitors a year, the vast majority arriving via airplane. Something unthinkable 100 years ago is now just routine for so many.

Air travel to Hawaii is actually an amazing story of innovation, imagination, and tremendous courage as well as a great deal of tragedy. Like most opportunities we have in our lives, it’s easy to take for granted the sacrifices that made them possible. So, it’s a dark path that eventually opens up into the sunny skies to the land of Aloha, and involves an event you may never have heard of, but which I don’t think you’re going to forget. Today, we’re telling the story of the Dole Derby. Keep your seatbelts fastened.

Orville and Wilbur Wright

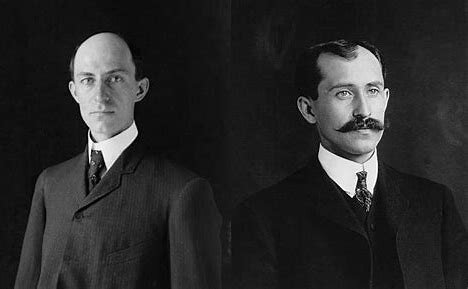

The Wright Flyer

Charles Linbergh

James Dole

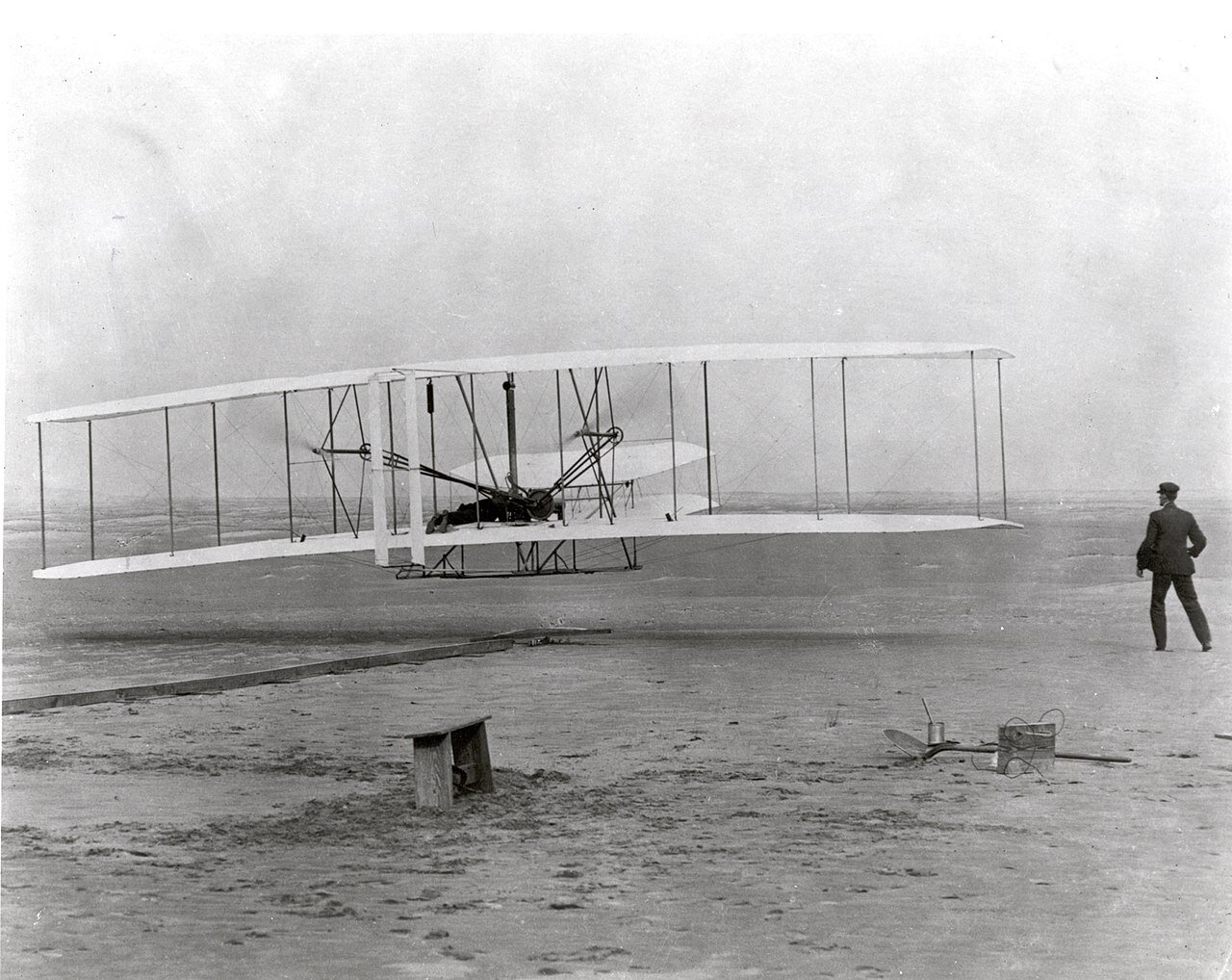

The Worlaroc

Arthur "Art" Goebel and and William Davis

Albert P. Taylor, James D. Dole, and Gov. Wallace R. Farrington, Wheeler Field

Harriet Quimby

Bessie Coleman

Martin Jensen and Paul Schluter

The Aloha

The Spirit of St. Louis Photo by Alan Wilson on Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Mildred Doran

Auggie Pedlar, Mildred Doran, and Vilas Knope

Dole Derby Images

Dole Air Race Starting Lines

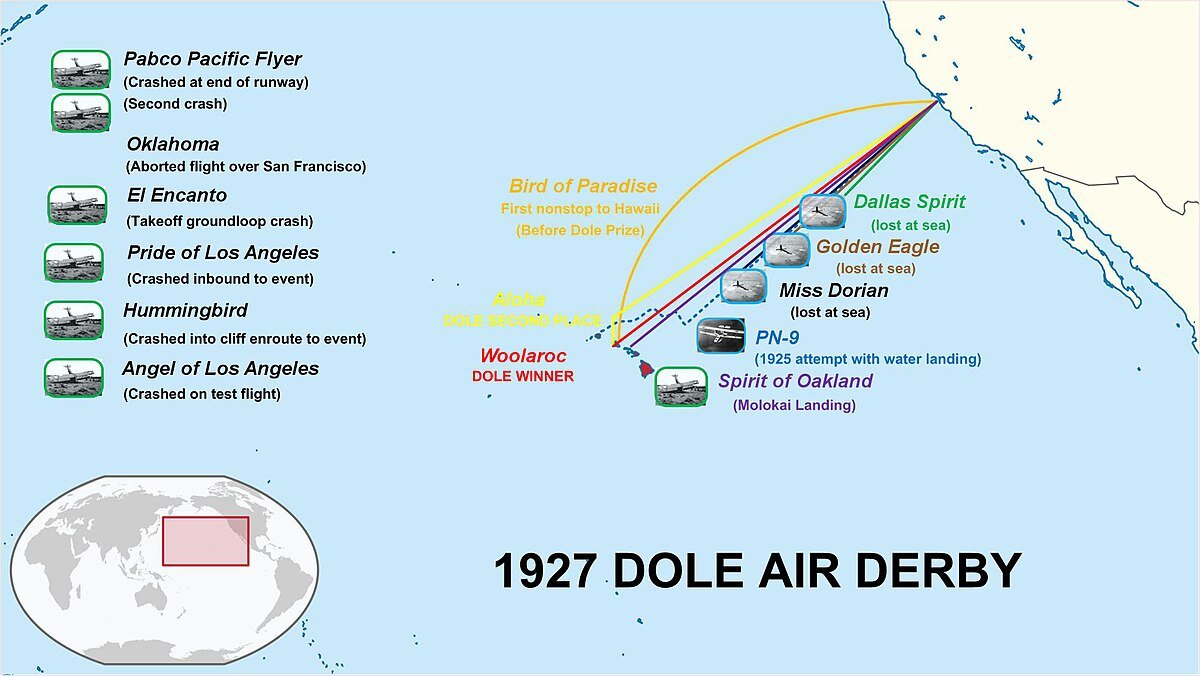

Dole Air Race Summary : By FlugKerl2 on Wikimedia commons https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Full Script

INTRODUCTION

Like other frequent travelers, I spend a lot of time on airplanes and have come to know the routine well – planning ideal routes, identifying the seats with legroom, scheduling the best times to travel and finding the best connections through efficient airports.

But all of these thoughts can divert your attention from the magic of flying...a machine that moves hundreds of people in a thin metal tube, miles above the earth at 500+ miles per hour. And, if you’ve ever flown an international route, you know that most of the time in the air is spent over water. I doubt it makes any difference in survivability if a plane were to go down, but somehow the act of flying over water adds an extra element of uncertainty for some.

And so as I prepare for my first overseas trip in over a year, I’m perhaps more thoughtful about how routine and safe air travel has become. And clearly, the airlines are anxious to get people traveling again...as I booked my ticket for a relatively sedate business destination, the website was rather insistent that I also consider a trip to Hawaii.

Ok, I’ll admit I looked and found the ticket price to be under $700. Flying from New York, the trip would take me about ten or eleven hours and cover almost 5,000 miles. On a flight like this, I’d be able to work for a few hours on wifi, write a chapter of my next book, then read or watch a movie on my ipad, and finally drift off to sleep. Then, I’d wake up a third of the way around the planet.

But if I described this flight to Hawaii to someone 100 years ago in 1921, it would indeed sound like magic. At this time, A trip to Hawaii required days on a boat from the West Coast. In 1921, commercial aviation was still in its infancy. The year of 1919 is often marked as the start of the commercial air travel market in the USA. Total passenger trips was measured by the thousands, instead of tens of millions like today.

Before the pandemic shutdowns, Hawaii welcomed over 10 million visitors a year, the vast majority arriving via airplane. Something unthinkable 100 years ago is now just routine for so many.

Air travel to Hawaii is actually an amazing story of innovation, imagination, and tremendous courage as well as a great deal of tragedy. Like most opportunities we have in our lives, it’s easy to take for granted the sacrifices that made them possible. So, it’s a dark path that eventually opens up into the sunny skies to the land of Aloha, and involves an event you may never have heard of, but which I don’t think you’re going to forget. Today, we’re telling the story of the Dole Derby. Keep your seatbelts fastened.

***

I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. And since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on instagram, or signup for our newsletter on our website, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, Thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 11, The Triumphs & Disasters of The Dole Derby

***

PART ONE: THE AVIATION CRAZE

Any story of air travel owes a little something to the Wright Brothers. On December 17th, 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright launched their so-called “Wright Flyer” for the very first time, traveling briefly through the air before bouncing back to ground. The inaugural flight lasted just 12 seconds, and the plane traveled only 120 feet.

The Wright Flyer would soar three more times that day, and the final flight shattered the mark set by the first – it stayed in the air a full 59 seconds, traveling 852 feet. Sadly, toward the end of the journey, a gust of wind wrecked the plane beyond easy repair, ending their historic day. These small distances may seem silly, but they represented the birth of modern aviation as we know it.

On that day in 1903, Charles Lindbergh was barely a year old. But a quarter of a century later, he would take the torch from the Wright Brothers, and carry aviation to an entirely new level.

Lindbergh flew his first solo flight in 1923, in Nebraska; and from there, he became a daredevil and a stunt pilot. He flew with the Army Air Service Reserve, and as an airmail pilot back and forth between Saint Louis and Chicago. He hungered for any opportunity to fly further, to push the boundaries. And when hotel owner Raymond Orteig offered $25,000 to the first pilot to travel from New York to Paris without making any stops, Lindbergh was determined to be the one to make the trip. The money helped, but it was mostly about the challenge.

Attempting this flight would put his life at risk, and he knew it.

He took off in his plane, The Spirit of Saint Louis on May 20th, 1927, and landed at Le Bourquet [Lu-Bor-Jae] Field near Paris. While the Wright Brothers had been thrilled to stay airborn for just short of a minute, Lindbergh’s flight took over 33 hours. It’s hard to imagine the thrill and the fear he must have felt, traveling over open ocean, entirely alone, defying our ideas of our limitations.

The flight of the Spirit of St. Louis inspired daredevil pilots all over the world. It became known as the “Summer of Eagles”, as pilots looked for new challenges to meet, new records to break. One man who took notice of the aviation craze was James Dole, part of the Dole family that controlled pineapple farming in Hawaii. He was no pilot, but he saw an opportunity to make news. So, just five days after Lindbergh’s flight, Dole announced a new challenge. These are his words:

“Believing that Charles A. Lindbergh’s extraordinary feat in crossing the Atlantic is a forerunner of eventual Transpacific air transportation, I offer $25,000 for the first flyer and $10,000 to the second flyer to cross from the North American Continent to Honolulu in a non-stop flight.” That 25,000 is worth almost 400,000 today.

Here was an opportunity to make history, and to one-up Charles Lindbergh. While the distance from San Francisco to Hawaii is 1200 miles shorter than Lindbergh’s flight to Paris, you spend much more of it over open water. And, more importantly, the island of Oahu was a significantly smaller target than France. Remember, there’s no radar on airplanes at this point, there isn’t even reliable radio communication. Not only would these pilots have to invent their flight path, they would have to invent how to navigate it, too.

Dole initially referred to his race as the Dole “Flight,” but it quickly became known as the Dole Derby. It was the natural next step forward in aviation history; but who were the people who were going to take it? In our episode about the Soviet Space Program, we talked about the nature of having “The Right Stuff”; the character attributes needed to be a pioneer in such a dangerous field. The Dole Derby attracted an extraordinary collection of people who possessed superhuman levels of bravery, ingenuity, and determination..

Pilots came to California from all over the country; so every region had personal favorites to root for. Nowhere was this more true than for the residents of Hawaii, itself ; because they had a local in the race, a 27-year-old Honolulu resident named Martin Jensen. Martin was born in Kansas and learned to fly in the Navy. Flying was such a part of his life that it’s how he met his wife Peggy. Peggy was a wing-walker, and if you’ve never heard of this unbelievable profession, you should look it up. Stunt performers used to walk out onto the wings of early airplanes in flight and perform acrobatics. Talk about having The Right Stuff. Peggy and Martin were even married mid-flight, with Peggy sitting in Martin’s lap at the pilot’s seat while with a judge in the passenger seat performed the service. After his naval service, Martin and Peggy briefly ran a company that delivered loads of lobsters by plane from Mexico to California. Eventually, they settled in Hawaii, where Martin Jensen flew tours of the islands.

Unlike daredevil pilots, or even his death-defying wife, Martin Jensen had a cautious personality, especially when flying over open ocean. His years in the Navy taught him to respect the dangers of the water. So when James Dole announced the contest, Martin was torn over whether he would participate or not. Perhaps more than other pilots, he understood the risks. Ultimately, though, the chance to represent Hawaii inspired him to set his fear aside. He left for Los Angeles on a steamer ship. He didn’t have a navigator, he didn’t have much money, he didn’t even have a plane! The plan was that Peggy would stay behind to find sponsors, while he searched for what he would need. The intensity of their search for funding and support was so high that it sent Peggy went to the hospital with a nervous breakdown. Rember, this is Peggy, the wing walking stunt lady.

On the day his application was due, Martin Jensen still didn’t even have a plane! So, he simply made one up, providing engine type, wing description, and more, all for a plane that did not exist. Amazingly, with less than two weeks to go, Jensen found a plane that wasn’t just available, but matched his imaginary description close enough to pass! It was missing a few things, like fabric on its framework, and wheels. Perhaps with a note of irony, Jensen did observe, quote, “I wish to point out that it did have an engine.” He worked furiously with mechanics to get the plane ready to cross the Pacific. When it was finally finished, he christened the plane as the Aloha, and cracked a bottle of seawater from Waikiki Beach across the plane’s nose.

Jensen’s mad-dash to prepare was not unique – it was a direct consequence of how The Derby was set up. There were only 9 weeks between Dole’s announcement of the race and the deadline to enter. It wasn’t just planes that were hard to come by – sponsors, money, navigators, all were in short demand.

One man who had no trouble securing his plane was pilot James Frost. He flew the Golden Eagle, one of the fastest planes in existence at the time. And its own just happened to be George Hearst,[hurst] son of the media titan William Randolph Hearst. Between the speed of the plane and the financial might behind the Hearst empire, most everyone expected Frost to take the prize.

Other pilots had to be more creative. Pilot Arthur Goddard sold his own airport in order to finance his plane. He designed it himself to include a bulging gas tank. Some thought it made the plane look pregnant.

World War One Ace Bill Erwin came from Texas, and made it known he intended not just to reach Hawaii, but fly on from there to Hong Kong, and then around the world. His pregnant, 20-year-old wife Connie, he said, would be his navigator on their plane, the Dallas Spirit.

And then there was the most thrilling pilot in the field, Arthur “Art” Goebel. Goebel was a Hollywood stunt pilot who was known as a daredevil among daredevils. His troupe traveled around the country, wowing audiences. The highlight of every show was when Goebel would perform mechanical operations on a plane in-flight – by flying up to intercept it in his own plane. The first time he did this, it wasn’t a stunt, Goebel watched another plane lose its landing gear mid-flight, loaded replacements onto his plane, took off, and fixed the other plane while both were still in the air. Was it pure heroism, or was it his drive to find ever more daring feats that even let him think of the idea?

Maybe fixing a plane mid-flight was just a natural step forward in a life of tinkering. Art Goebel had been working with machines since he was a kid fixing bicycles. He graduated to motorcycles, and then to cars. But he was always dreaming of planes. It’s claimed that, after first seeing one as a little boy, he had to wait seven years before seeing another. The long absence only deepened his obsession.

He briefly enlisted in the Peruvian army, hoping for a chance to fly in their air force, but he just missed the end of combat. Instead, he flew as an air courier in South America before returning to Los Angeles in 1923. There, he became a member of the famous “13 Black Cats,” a group of stunt pilots known to be such insane risk-takers that they intentionally invited bad luck their way. Their name reflected that – 13 Black Cats. Double bad luck.

It was with the Black Cats that Goebel first visited Hawaii. On a quick flight around the islands, he screwed up a landing, crashing into the runway. It was the first time he’d ever crashed, but not only was he uninjured, he was undeterred: The Black Cats had come to the Islands from California via steamer ship, but Goebel declared “next time I come to Hawaii, I’m going to fly.” In many ways, this story to me sums up the attitude of these pilots most clearly— rather than being discouraged by what may have been the most dangerous or most terrifying moment of his flying career, Goebel was focused by the thrill, inspired by it.

Naturally, upon hearing Dole’s announcement, Art Goebel began securing funds to buy a new plane capable of the transpacific crossing. He sold many of his other planes designed for lesser distances, and even sold most of his possessions. He took out loans. He found donations. And he secured his final bit of funding by befriending oilman Frank Phillips. Phillips lived on a ranch named “Woolaroc,” [wu-luh-raak] (a portmanteau for Woods, Lake, and Rocks), and the two men agreed that name to Goebel’s new plane: “Woolaroc.”

Once the pilots had secured their planes, their next steps were to find navigators. This task was potentially even more difficult than finding planes. As the crossing was so new and unique, no one could even agree on what experience or qualifications a navigator would need. No one would know if their technique was efficient or safe until they were already in the air.

Martin Jensen of the Aloha put an ad out in the paper, and found a navigator working on a merchant ship, Paul Schluter. Schluter had an impeccable background for the job, but just one drawback: Paul Schluter had never been on a plane. Schluter in particular fascinates me – what impulse was so strong in him that it pulled him into a new experience like this in such a high stakes situation?

Bill Erwin from Texas, originally planned on using his wife as his navigator. However, once reality set in, her youth and pregnancy just made it too inadvisable; so he hired a navigator named Alvin Eichwaldt. The two quickly developed a rapport, with Erwin frequently threatening to push Eichwaldt off the rescue raft in the event that their plane went down.

Daredevil Art Goebel hired an active member of the US Navy, William Davis, Jr. In a field of pioneers and risk takers, he stood out as a paragon of cautious level-headedness. But if he was going to fly, Davis had to request a leave of absence from the Navy. With just 3 days before the race was set to begin, his plan was to hitch a ride from his base to Oakland in The Spirit of John Rodgers, a competing plane flown by fellow Naval Officers. But as the Spirit was preparing to take off, Davis still hadn’t received word on whether his requested leave was granted or denied. When his approval finally arrived, he sprinted to the airstrip, just in time to watch the flight take off without him.

Fifteen minutes later, the Spirit crashed into a cliff, killing the pilot and navigator inside. Davis was shaken by the incident. He was alive as a consequence of pure luck, by a matter of just mere minutes. But he didn’t turn back. He made his way to Oakland.

The Spirit of John Rodgers wasn’t the only plane on its way to the starting line. One day after it crashed, another contestant, The Pride of Los Angeles, failed in its final approach to the Oakland airstrip and crashed into the bay. Luckily, a fireman on shore tied a rope around his waist and swam to the rescue of the crew.

The 7,000-foot airstrip at Bay Farm Island was simple and basic, with essentially no infrastructure around it. But as the race approached, it filled up with crowds – the pilots and navigators and their families, journalists covering the race and angling for interviews, mechanics, fans, and more. The journalists all lodged in a wooden shack, while the aviators parked their planes outside of their tents. Even though the goal was to change the world of aviation, it was a carnival atmosphere, with excited spectators milling around the temporary structures, hoping to catch glimpses of test flights and more.

And the most fascinating person there was someone we haven’t even talked about yet. She wasn’t a pilot, nor a navigator. She was a passenger. Her name was Mildred Doran [Door-AAn or D-uh-r-ih-n], the only woman who would be on any of the flights. J – and just by being there, she was fulfilling a dream that she had to work harder for than just about anyone there.

***

PART TWO: MILDRED DORAN THE WOMAN AVIATOR

In 1911, the journalist Harriet Quimby became the first American woman to earn a pilot’s license. She then became the first woman to fly across the English Channel. In 1922, Bessie Coleman became the first woman of Black descent and of Native descent to earn her license. She had to work a little harder, though – no American school would take her on as a student; so she learned to fly in France.

By the time the Dole Derby came around, both women were, sadly, dead— Quimby had been tossed from a plane in 1912, and Coleman fell to her death in 1926.

Other women wanted to participate in the Derby. Two women in Dallas, for instance, announced that they would fly with any pilot who would take them. One carried a note of permission from her husband, while the other said she would go despite her husband’s wishes. But the only one who made it to the starting line was Mildred Doran.

Mildred was born in Canada, and grew up in Flint, Michigan; which was already becoming one of the centers of the auto industry in America. Her mother passed when Mildred was 14, leaving her to help her father care for and raise 3 younger siblings. By all accounts, Mildred balanced her responsibilities remarkably – finishing her high-school education, working part time jobs to financially contribute, and playing the role of surrogate mother for her siblings.

After high school, Doran trained for a year to become a schoolteacher. Her teaching assignments took her deep into rural Michigan, hours away from Flint; and on trips home, she would frequently catch a ride on a plane belonging to William F. Malloska, a family friend and owner of the Lincoln Petroleum Products Company.

Even before she started flying home regularly, Mildred was fascinated by planes. She’d seen an aerial stunt showcase while she was in college, and she said, quote: “I didn’t have a ghost of an idea about how they worked, and machinery never interested me, but the planes themselves looked so alive that I loved looking at them,” end quote. At the showcase, a friend pressured her into paying for a ride, calling her a coward if she didn’t try. Mildred said she returned from the flight a changed woman, with a new level of fearlessness for life. She’d devoted so much of her life to caring for others, to fulfilling responsibilities, and now she saw her entire world from a new perspective.

She took every opportunity to fly as a passenger after that. She became particularly close to two pilots – E.L. Sloniger [sl-awe-ni-g-er] and John “Auggy” Pedlar. When Charles Lindbergh announced his attempt to fly across the Atlantic, it was with these two men that Mildred revealed her dream to become the first woman to make a similar flight. Both declared that they would gladly accompany her should the opportunity ever present itself. And Mildred’s family benefactor, William Malloska [Mall-usk-ah], quickly gave them the opportunity to turn that dream into reality: the day before Lindbergh took off, he put in an order for a plane that could survive a similar trip. It would be ready in time for the Dole Derby. When asked about the faith Malloska placed into Mildred, he said, quote:

“I have all the confidence in the world in Miss Doran. I know of the hardships she endured after the death of her mother. She was able to go to school only a half of each day, worked in a telephone office the other half, and in addition took care of all the housework and was a mother to her younger sister and a young brother. She will go through this flight just as she has gone through other hardships.”

Now Mildred had a painful choice to make, between two eager and capable pilots who both wanted to fly the plane for her. Would it be Sloniger or Peddlar? Even this was an opportunity for a bit of publicity – the three of them went to the offices of a local newspaper, The Flint Journal, in order to flip a coin. The coin rolled under a desk, and had to be carefully lifted to reveal what side it had landed on. And so fate decided that Auggy Pedlar would be the man to pilot Mildred from Oakland to Hawaii.

Mildred was still only 22 years old, and knew from the start that she would be risking her life. But she said this, quote: “I simply desire to do something different and to be the first woman to do it. I am sure we will win, but if we don’t life is nothing but a chance, anyway.” End quote.

I’ll pause there so we can reflect on the power of her statement....beautiful and powerful in it’s simplicity… her desire led to a goal to achieve which led to action...all while acknowledging that success requires risk. Achievement without risk is nothing better than a participation medal.

But back to our story….

Their new red-white-and-blue plane was christened the Miss Doran. As they prepared to depart Flint, they cracked a bottle of ginger ale across it – they couldn’t use anything harder, it was still Prohibition. It took over 3 weeks to make their way to Oakland, but they made the most of it. They made publicity stops in Chicago, St. Louis, Tulsa, Fort Worth, El Paso, Tucson, Long Beach, and more. Every stop attracted new fans, and new journalists following the story of the woman who was nicknamed “The Flying School Marm.”

On the final leg of the journey, the plane was rattling so much that Pedlar, Mildred, and the accompanying crew threw their tools out the window in order to stop the noise. This turned out to be too much tempting of fate – their engine misfired and they were forced into an emergency landing in a remote field. A group of journalists retrieved Mildred to drive her the rest of the way to Oakland, while Augie and some of the entourage following them did their best to fix the plane without the proper tools.

By the time Mildred reached Oakland, she was a media sensation. Journalists asked her if there was any romantic interest between her and Auggy. Her response was pretty radical for the 1920’s. Quote: “I don’t want to fall in love and marry, and neither does Auggy. He and I both want to do a lot of things, see a lot of things.” End quote.

She admitted to knowing nothing about how the plane worked, nothing about how to swim, she even told the crowd that she refused to pack a life preserver. Mildred’s flight would be an act of faith – her advantage in the race, she had decided, was her sheer determination. “We are not going down out there,” she said. “We are going to stay up until we reach land.”

***

The race was set to take place on August 12th. But as the date approached, there was increasing concern about whether the planes, the pilots, and the navigators were adequately prepared. There’s no such thing as being 100% ready to do something nobody’s done before. Race officials were extremely nervous, and pressured James Dole to delay or even cancel the event. As one official put it, quote: “This is a supreme test of aerial naviagtion. An error of but a couple of degrees on the part of the navigator would send a plane at least 200 miles off the course, and such would spell disaster for the fliers.” End quote. Insurance agents began to pull out. Newspapers, which had been overwhelmingly supportive of all the hullaballoo, began to raise concerns. Privately, one official said that taking off on August 12th would be nothing short of suicide.

Dole allowed for last-minute efforts to prepare the contestants: exams for navigators, requirements for fuel, test flights, and more. But he refused to delay the race. We don’t have anything on the record to tell us why; but, interestingly, most of the pilots agreed – they wanted the race to go forward. So many of them had put everything they had into this.

But finally, with weather reports looking grim, and multiple fatal accidents like the crash of the Spirit of John Rodgers that we told you about, everyone finally agreed, on the night before the race, to delay for four days. As if to confirm the danger even further, the next morning, August 12th, a plane called Angel of Los Angeles crashed during a test flight. The pilot, an experienced British flying ace named Arthur Rodgers, attempted to parachute to the ground, but died, all with his wife and child watching.

For William Davis, the cautious and cool-headed navigator of the Woolaroc, it might have been seen as a second brush with death. Remember that he had planned to fly to Oakland on the doomed Spirit of John Rodgers just a couple of days before. He seemed the only contestant whose faith and confidence were not absolute. This led to him being described in the press as the least courageous of the contestants, but I wonder if it’s the absolute opposite – the fact that he, more than anyone, was aware of the dangers, and still prepared to face them.

“Scared?,” Davis said, “Sure. Anyone that doesn’t feel a few chills along the spinal column at the prospect of starting out over a 2,400-mile expanse of water with only the perfect functioning of a manmade and therefore fallible piece of mechanism between himself and eternity, is made of sterner stuff than I am.” End quote.

Finally, August 16th, 1927 arrived. The cautious Davis noticed at breakfast that all of the waiters were particularly solemn. Tractors rolled over the runway, and water trucks sprayed mist onto the airfield, as the crews attended to their planes. As many as 100,000 fans were watching in-person; even from across the San Francisco Bay, as spectators claimed high ground, and nearby hospitals rolled patients out in wheelchairs to give them a better view of the sky.

Martin Jensen was the first to take to the runway, in order to make one last practice flight in the Aloha. Taking off and landing with large supplies of fuel was dangerous, so none of the competitors had actually attempted flight with their entire fuel supply.

Pilot Bennet Griffin, whose plane was called The Oklahoma, said goodbye to his fiancé. They had tried to be married the previous day, but didn’t know that California required a three-day wait for a marriage license. So the new plan was that his fiancé would follow him to Hawaii by boat, and marry him there.

By noon, most of the morning’s fog had cleared and the pilots made their final preparations. Ultimately, 8 planes would attempt take off that day. The Oklahoma was first in line, to be followed by El Encanto, the Pabco Pacific Flyer, Golden Eagle, Miss Doran, Aloha, Woolaroc, and finally the Dallas Spirit.

The Oklahoma needed a crew of mechanics pushing it down the strip in order for its engines to start, and then it lifted off the ground and took off, it disappeared into the fog.

At 12:03, El Encanto attempted to follow suit. But a crosswind at caused it to crash its left wing into the runway. A group of journalists had to scatter to avoid being hit by the plane. Its pilot and navigator crawled out of the wreckage and waved to the crowd. The pilot said, “I would have rather crashed in midocean than to have this happen.”

The Pabco Pacific Flyer was briefly delayed as the wrecked El Encanto was cleared from the runway. It attempted takeoff at 12:11pm, bouncing from the ground into the air and back down 7 times, before finally running out of room on the runway. They were forced to cut the ignition and stop.

At 12:31pm, betting favorite the Golden Eagle, with the might of the Hearst family fortune behind it, took off with no issues.

Next, Mildred Doran climbed into the Miss Doran with a good luck note from her father tucked into her pocket. They took off successfully at 12:33.

One minute later, Hawaii’s hometown hero Martin Jensen took off in the Aloha. Right before takeoff, a courier raced through the crowd to reach Jensen, and deliver the final $300, wired by his wife, to settle accounts with his mechanics. From the air, Jensen dropped flowered leis into the crowd.

After Aloha came the Woolaroc, which also took off successfully.

The last plane was Bill Erwin’s Dallas Spirit; but as it prepared to take off, spectators pointed to the sky. A plane was coming back to the runway. It was the unmistakable red-white-and-blue Miss Doran. It had been in air for only 12 minutes before motor troubles forced it to turn around. Landing with a nearly full tank of gas was extraordinarily dangerous, the navigator held Mildred by an open doorway, ready to throw her out of the plane if it caught fire. But miraculously, they landed fine. Still in the race, they worked feverishly to repair the motor. Mildred was consumed with frustration, but as determined as ever. “If they force us down seven times,” she said, “I’ll go up again the eighth.”

In the meantime, The Oklahoma also returned. Its engine had overheated. Pilot Bennet Griffin abandoned the race, but found that he was just happy to be alive; and he married his fiancé in California, after all.

He wasn’t the only racer to return. The Dallas Spirit abandoned its attempt after a half-hour.

Finally, the Miss Doran took off once more at 2pm.

Out of all the pilots who had set out dreaming of the Dole Derby, 3 planes had crashed just trying to get there. Only 8 planes were able to attempt a takeoff. And two hours after the start, only four of those eight were in the air: Woolaroc, Golden Eagle, Aloha, and Miss Doran.

The Golden Eagle was likely in the lead, given its earlier start time and its speed; but it was impossible for anyone to know for sure. Its radio system could only receive signals, not broadcast them. It’s staggering to me, with the infrastructure we now have for flying, just how alone they all were up there, as they left the continent behind.

At 3 in the afternoon, the Miss Doran was seen passing the Farallon [feh-ruh-laan] Islands –the last bit of inhabited earth the crew would pass over before reaching Hawaii. Escort planes saw Auggy [Awe-g-ee] the pilot in his straw hat, and Mildred waved happily to the escort planes as they turned around to return to California. After so much effort, such a long journey, so many obstacles standing in her way, I can only imagine the sheer joy and true sense of self Mildred must have felt as those other planes turned back, leaving herself and Auggy with nothing but sky and sea before them, racing towards history.

***

PART THREE: THE RACE AND ITS WINNERS

I want to take a moment before we talk about the flight to share something we haven’t acknowledged yet. By the time the Dole Derby got underway on August 16th, 1927, the original goal – to be the first to fly non-stop from California to Hawaii, had already been achieved, by pilots who were not in the race. And not just once, but twice. On June 28th, Army Air Corps Lieutenants Lester J. Maitland [mayt-luhnd] and Albert F. Hegenberger [Hae-gen-burger] flew an Atlantic Fokker C-2 military aircraft from Oakland to an airfield on Oahu in 25 hrs. and 50 minutes. Then, on July 14th, the first civilian team made a successful flight – well, “successful” is a relative term – they ran out of fuel before landing, never reached Oahu, and crash-landed in a thorn tree on the island of Molokai. But they survived and, technically, they reached Hawaii.

So what was the Dole Derby about at this point? In part it was about seeing what civilians could do with their own ingenuity and mettle. But I think there was also something about the fever of the event that made it so hard to even consider delaying the start. The appetite to connect the globe with airplanes had been awakened by Lindbergh’s flight, and the combination of Dole’s prize money, the publicity, and the competition between this remarkable collection of daredevils and pioneers made it even more irresistible.

So by the time four planes flew out over the Pacific Ocean, it was proven that it could be done. But every plane was different, every team in the cockpit was different; and so nobody could attempt this feat in the same way as anybody else.

Inside the Woolaroc, Art Goebel and William Davis flew through blankets of thick fog. They had brought smoke bombs with them to measure wind drifts; the fog rendered them useless. They used radio signals and broadcasts from the US Weather Bureau, hoping the predictions they provided were accurate. The engine roared so load that they couldn’t even speak to each other. They rigged up a clothesline and sent handwritten notes back and forth along it.

“There was plenty of time to think,” Goebbel said. “Lt. Davis and I were as completely separated as if we had been at extreme ends of the Earth.”

Far below the Woolaroc, Martin Jensen’s Aloha was flying its own path. Because Paul Schluter had been a ship’s navigator, he wanted to stay below the fog and close to the water, where he’d be more comfortable navigating. They were cruising only 40 feet above the waves, sometimes almost touching the water. Once, they narrowly avoided crashing into a steamer ship.

They had trouble with fuel distribution from the start, and had to pass oil through tubes using their mouths. Their became so afraid of running out of fuel that they strapped supplies to their bodies just in case they had to abandon the plane.

And then, as the sun set, the darkness brought them new problems. Jensen had no modern instruments for keeping the plane level; and in the pitch black, if he was off by even a little, they would crash into the sea. They attempted to rise above the fog, hoping that if they got far enough up, they could navigate by the stars and have a larger margin for error, but each attempt sent them in a tailspin toward the water. They had no choice but to trust Jensen’s instruments to keep them level the whole night.

By contrast, inside the Woolaroc, William Davis was grateful when the sun began to set. Their plane was able to stay at higher altitude, allowing him to use the stars to stay on course. Their plane was one of the only ones with outgoing radio capabilities, and Davis took the opportunity to send a message to his family “Seven hours out. Everything going well. Love to all.”

But in the pilot’s chair, the daredevil Art Goebbel did not feel the same way. He had an almost superstitious fear of the darkness descending them that evening – he couldn’t pin it on anything, but he felt unnerved all the same. He said he feared, quote “The long hours of darkness ahead. The sun went down. It had been a good friend, and the weather had been fine. Now night was coming on, and with it a loneliness that cannot be described and which has not been experienced by any, except those who, like us, have headed a plane into darkness over water… I prayed in my heart that nothing would keep me from seeing that golden sun again.” End quote. It’s revealing to me that at this moment, fearless pilot Art Goebbel of the 13 Black Cats, and the cautious, level-headed William Davis, whom the press had called cowardly, had switched roles.

In Hawaii, between 20 and 30 thousand people had already gathered at the airstrip, even though no plane was reasonably expected to make it before late morning or early afternoon the following day. Among them was Peggy Jensen, Martin’s wife, who had to endure multiple rumors that her husband’s plane had crashed. Ironically, none of James Dole’s own employees were in the crowd themselves. They were still picking pineapples – he didn’t give them the day off.

The sun came up, and Goebbel’s prayer was answered – the Woolaroc was still in the air. Between the stars and their radio beacons, they could even be confident that they were on course. Their biggest concern now was whether they had enough fuel to make it to the islands. Davis put a note on their clothesline for Goebbel, saying they had 3 more hours to travel, and asking how many more hours’ worth of fuel they had. When Goebbel sent a response, it was just a single number, and it terrified even the cool and collected Davis. On the note, he saw the number “2”.

Meanwhile, in the Aloha, Jensen and Schluter were having similar fears about their fuel supply. Though they had survived the incredibly dangerous night over the ocean, they were forced to fly the plane in circles for several hours, waiting for the sun to be in just the right position for navigation. Jensen had two choices, either of which could doom them – wait for the sun and risk running out of fuel, or fly blind, and risk missing the islands completely. Even though he knew it could be their death sentence, Jensen decided to allow the delay; and hope their fuel supply would hold.

While the Aloha spun in circles, the Woolaroc raced its own dwindling fuel supply. Finally, Art Goebbel spotted a small smudge on the horizon; which grew larger with each passing minute. It was Molokai, one of the Hawaiian Islands. Then, another smudge, the island of Maui. William Davis said, “A more beautiful sight I have never witnessed”. Though they were sure they were too late to have won the race, the sight of dry land gave a sense of incredible relief, that maybe the worst of the danger was over.

They reached Oahu, and flew over the city of Honolulu. The whole city seemed empty; and made them believe that all the excitement of the race must have ended hours before.

But they were wrong. The reason Honolulu seemed so quiet was that anyone who could be there was at the airstrip. Suddenly, military escort planes appeared alongside them, and one of the escort pilots signaled them with one raised finger. The Woolaroc was in first place. They landed at 12:23 PM (Hawaiian Time,) a total flight time of 26 hours and 17 minutes. The massive crowd swarmed them as they triumphantly exited the plane.

William Davis was flabbergasted, and confused, by their success. He asked Art Goebbel how they’d flown three hours when his note said that they only two hours of fuel left. And Goebbel laughed – in all the sleepless hours and adrenaline, Davis had misunderstood the handwriting on the note. They didn’t have two hours of fuel, they’d had five.

Peggy Jensen rushed from the crowd to Goebel, kissed him, and begged him for information on where her husband Martin was. Sadly, Goebbel had no information to give her.

But Martin Jensen was still alive. When the sun finally rose enough to get a reading, Paul Schluter determined that they had drifted 200 miles to the north of their course. This told Martin that if they had pressed on without waiting, they would have been lost at sea.

This also meant that, when the Aloha arrived in the Hawaiian Islands, at 2:22pm, they arrived over the Waianae Mountains, a direction no one expected to see them coming from. The hometown favorites had made it safely, and Peggy’s husband had come home.

But the celebrations for the Woolaroc and the Aloha were short-lived. There were still two planes that had started the race, and the afternoon was passing with no sign of the Golden Eagle or the Miss Doran were spotted. If either plane was going to arrive, it should have arrived already. But they hadn’t; and they wouldn’t.

The Golden Eagle and the Miss Doran were missing.

***

The Navy ordered 40 ships to search for the fallen planes, and many private ships joined in the hunt, too. Even if the planes were no longer in the air, there was a chance that the crews were still afloat, somewhere. James Dole offered a 10 thousand dollar reward for the rescue of either crew. Mildred Doran’s sponsor William Malloska also offered $10 thousand for her return, and the Hearst family offered $10 thousand for the discovery of the Golden Eagle.

Family members of the crews waited by telegram machines and in newspaper offices for word of either plane. Both the Woolaroc and the Aloha joined in the search efforts. Probably neither had imagined being back in the air so soon. Peggy Jensen joined her husband on their flight. Martin said, quote: “I will not rest— I have no plans— there is only one thought in my mind, and that is to save my buddies.” End quote.

Goebel and Davis issued an emotional statement to a similar effect, before flying out to look for the planes:

“In the light of what has happened, we forget the hero-worship that has been forced upon us. We forget the material gain that has come from our quest. All that we can think of today is that we want to wind up our Whirlwind again, and if we can but be granted another triumph from the fates, go soar out from the scenes of our own little happiness, and give all— if necessary— that our less fortunate friends may be brought safely into port.”

It’s extraordinary how much this challenge bonded the participants, who had never met before they assembled in Oakland, and now felt so inseparable that they would risk their lives for one another. We might think of them as reckless, as glory-seeking, as foolhardy; but when the call for a deeper kind of bravery went out, they took to the skies again with no hesitation.

Even back in California, the Dallas Spirt, which had failed to take off for the race, now took off for search and rescue. Bill Erwin and his navigator, Eichwaldt, decided to fly toward Hawaii in a zig-zag pattern, hoping to cover the most ocean. Erwin still intended to take his wife to Hong Kong, but this mission called to him first.

They took a radio with them in order to keep the navy updated of their progress. Eichwaldt’s earliest updates were hopeful and light-hearted, he would even inform listeners that Bill Erwin had just sneezed. But then, at 9 PM, they broadcast an SOS message mentioning a tailspin. After a brief silence, they came back on to say that they were okay. That message was interrupted by another tailspin. And that was the last anyone heard from the Dallas Spirit.

And as for The Golden Eagle and the Miss Doran? No sign was ever found of either plane or crew.

***

PART FOUR: CONCLUSION

The final accounting of the Dole Derby is this. Two planes successfully landed. Eight airplanes crashed. 10 aviators dead or missing. The Philadelphia Inquirer described the race as an “orgy of reckless sacrifice,” while the Syracuse Post Standard called it “a gamble at long odds against suicide. The Virginian Pilot condemned it as “criminally wasteful of human life.” Questions persisted about whether James Dole had been irresponsible in giving the teams so little time to prepare, and provide so little in the way of support in case anything went wrong.

But the Boston Daily Advertiser, mourning the late Mildred Doran, struck a different tone:

“If Mildred Doran is today a ghost, she is a ghost which regrets nothing.”

This quote sticks with me. As often as she struck a defiant tone, Mildred surely knew the risks of what she was doing. She knew it when she first got in a plane. She knew it when she entered the Derby. And she knew it when they nearly crashed on the day of the race, and decided to take off again anyway.

People who can conquer fear like this are precious to humanity. Anyone who is willing to risk it all for the sake of progress, for the idea of doing something nearly impossible, just so it will be a little easier for the next people to try, should be remembered reverently.

But it’s not enough just to celebrate that rare courage. The example set by Mildred Doran and all the others has to remind us to spend that courage wisely. The Dole Derby is a crucial chapter in the development of air travel, it’s part of what makes it so easy for anyone to enjoy a Hawaiian holiday today. And it’s probably inevitable that this kind of progress required risk, and lethal levels of danger.

For years, rumors persisted about the lost planes. Some speculate that the Golden Eagle, the flashiest aircraft in the bunch, flew too fast, and overshot Hawaii in the night. Others spread rumors that bottles were washing ashore, containing notes written by the lost Mildred Doran. These rumors and legends, I think, are part of how we mourn these pioneers. They’re mementos on the dark path towards progress, towards making the impossible normal.

Before leaving for the rescue attempt that ultimately took his life, Bill Erwin wrote the following note:

“Tomorrow begins the great adventure. Flying personifies the spirit of man. Our bodies are bound to the Earth; our spirits are bound by God alone, and it is my firm belief that God will guide the course of Dallas Spirit tomorrow over the shortest route from the Golden Gate to the isle of Oahu … If we succeed it will be glorious. Should we fail, it will not be in vain, for a worthy attempt could never result in a mean failure…. I hold life dear, but I do not fear death. It is the last and most wonderful adventure of life…. We will make it because we must, but whatever comes, I am the master of my fate, and God willing, the captain of my soul.”

The next time you take a flight out over the ocean, take a moment to look down and imagine how dangerous those waters once were to travelers; and, if you can remember, say a little thanks to the daredevils of the Dole Derby.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Emily Wolfe and our new producer Evie Hendrix; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Samuel French. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle and our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. Lastly, thank you for listening. You have more choices than ever about where to spend your time. I’m grateful that you’ve chosen to spend some time here, with me, walking my Dark Path together. And don’t hesitate to reach out via email – explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you. I really would!

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me, your host, MF Thomas. Until next time, good night.

-END-

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING:

https://www.chicagoreviewpress.com/race-to-hawaii-products-9780912777252.php

http://archives.starbulletin.com/2003/12/29/features/story2.html

http://archives.starbulletin.com/2004/01/05/features/index2.html

http://archives.starbulletin.com/2004/01/12/features/index.html

https://www.nps.gov/wrbr/learn/historyculture/thefirstflight.htm

https://archive.org/details/greatadventurest012839mbp/page/n177/mode/2up

Actual newsreel footage of the participants and some of the takeoffs:

https://archive.org/details/DoleAirR1927

MUSIC:

Stacks, Elision

Brenner, Falls

Nuclear Conception, Alice in Winter

Paths of Glory, Stephen Keech

Moonchild, Elision

Color of Distance, Chelsea McGough

Perfect Spades, Third Age