Episode 12: The 18th Century Automaton Who Beat Napoleon

The Museum of Automatons is packed with automatons... mechanical figures that move and speak. Imagine what Walt Disney would have designed in the 18th century - automatons were attempts to mimic human figures in remarkable ways. Really, just the first glimpse at the future of robotics...or at least robots that would mimic humans and other animals. But automatons weren’t just gifts wealthy European families commissioned and gifted to others. An automaton like some exhibited here defeated Napoleon at the height of his military and political power. But it didn’t beat him on the battlefield. It defeated him on a chess board.

Empress Maria Theresa.

Joseph Hickel Joseph II

Jospeh II and his parents

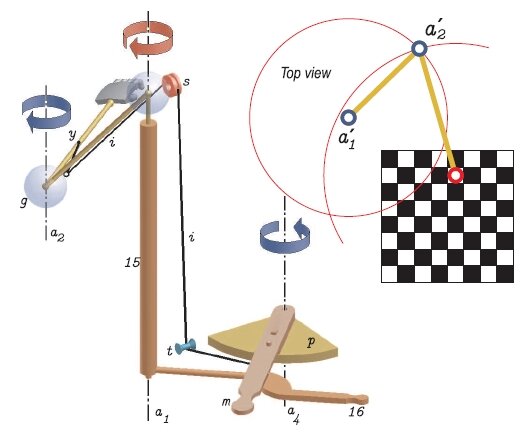

Kempelen Speaking Machine Replica

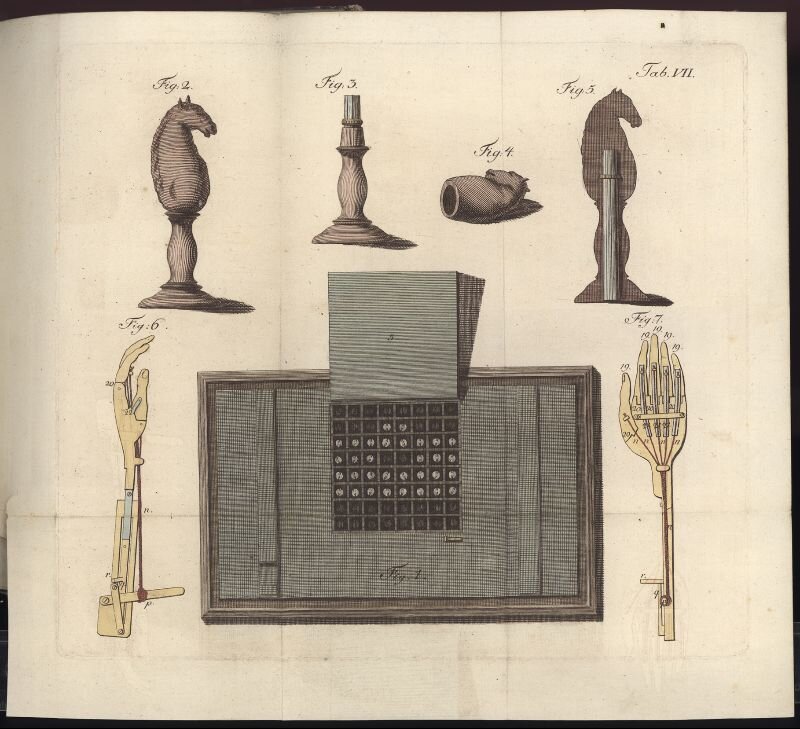

Mechanics of the chess board

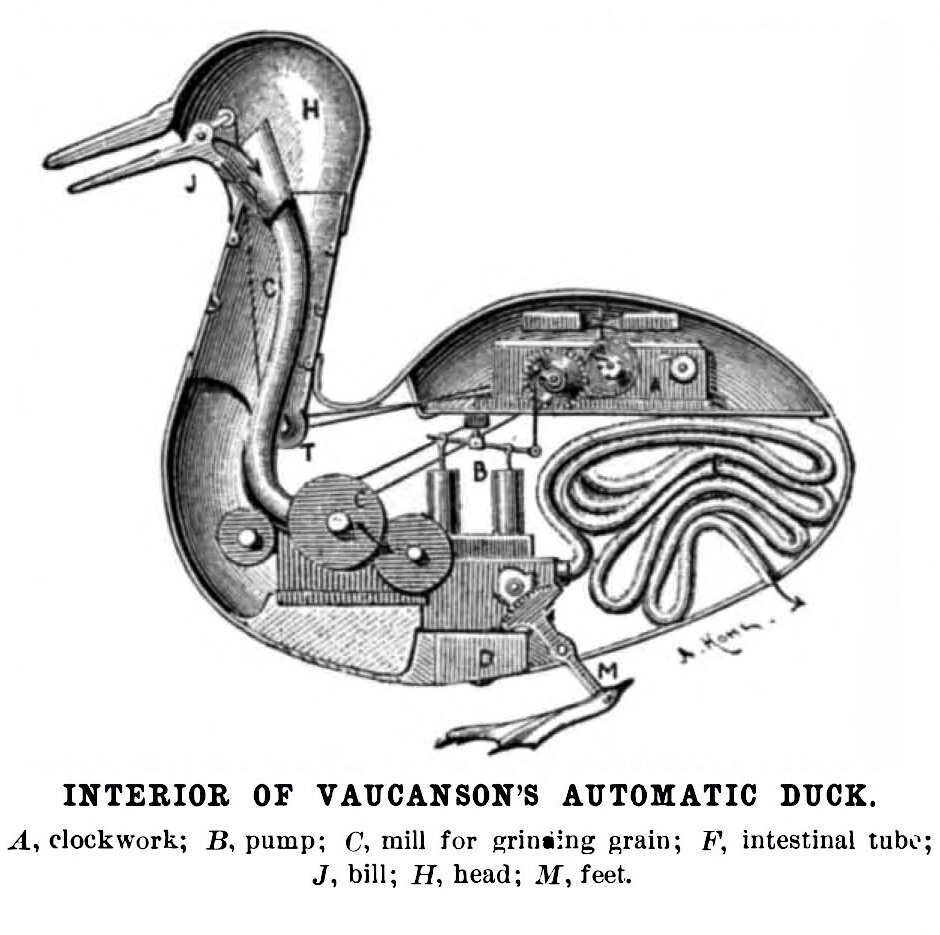

Digesting Duck

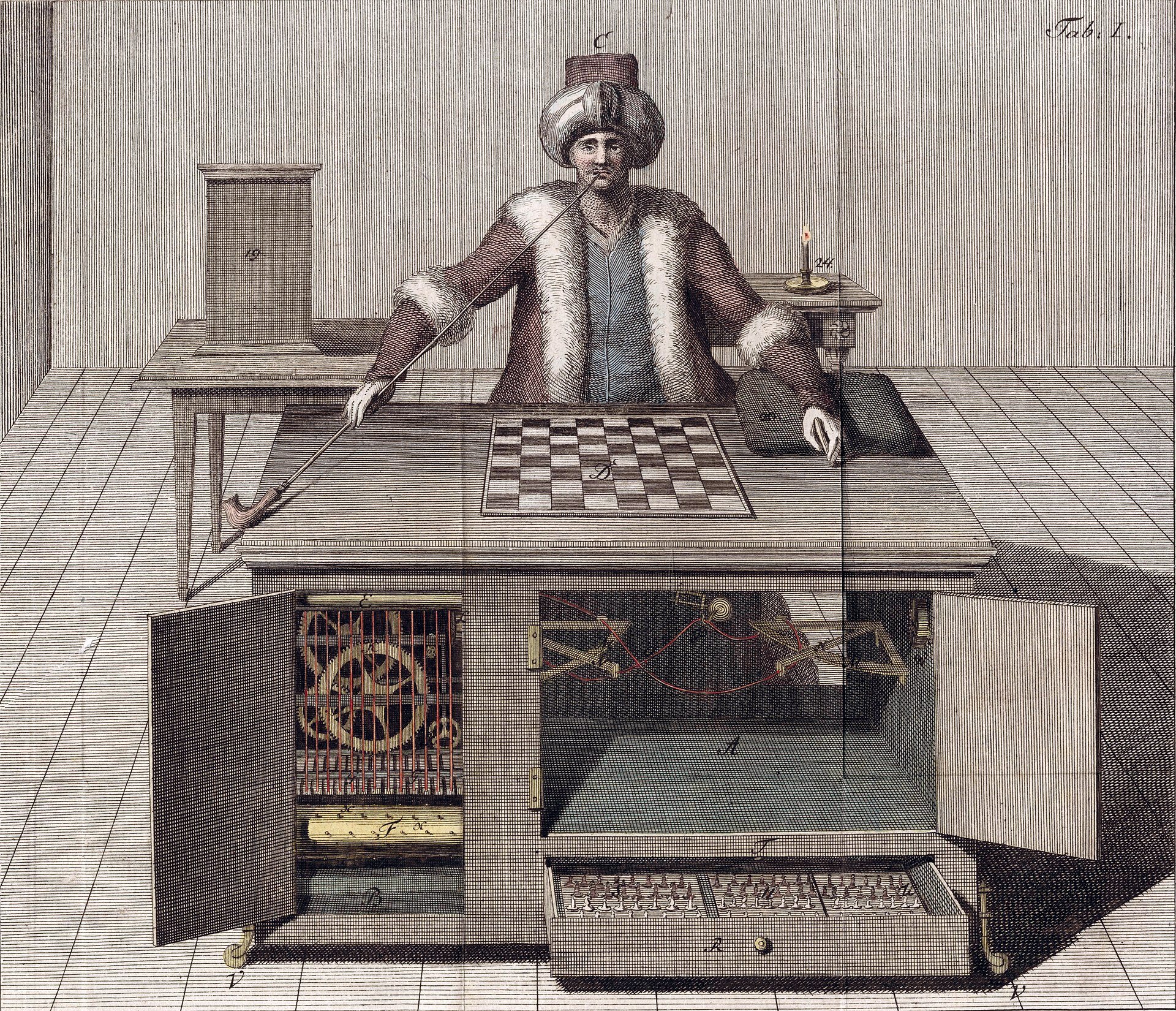

Reconstruction of the Turk

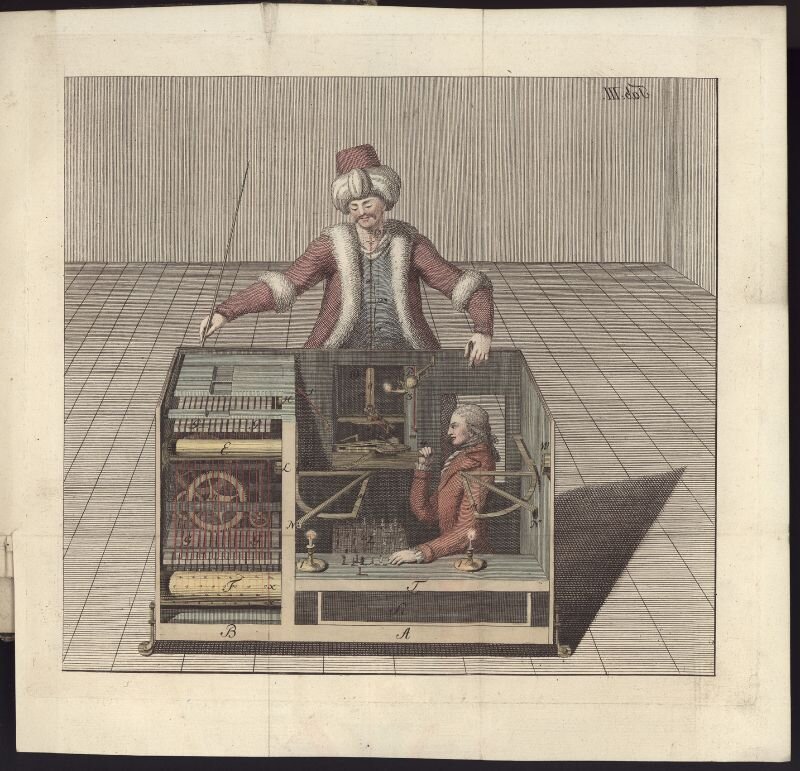

The Turk Detailed Illustration

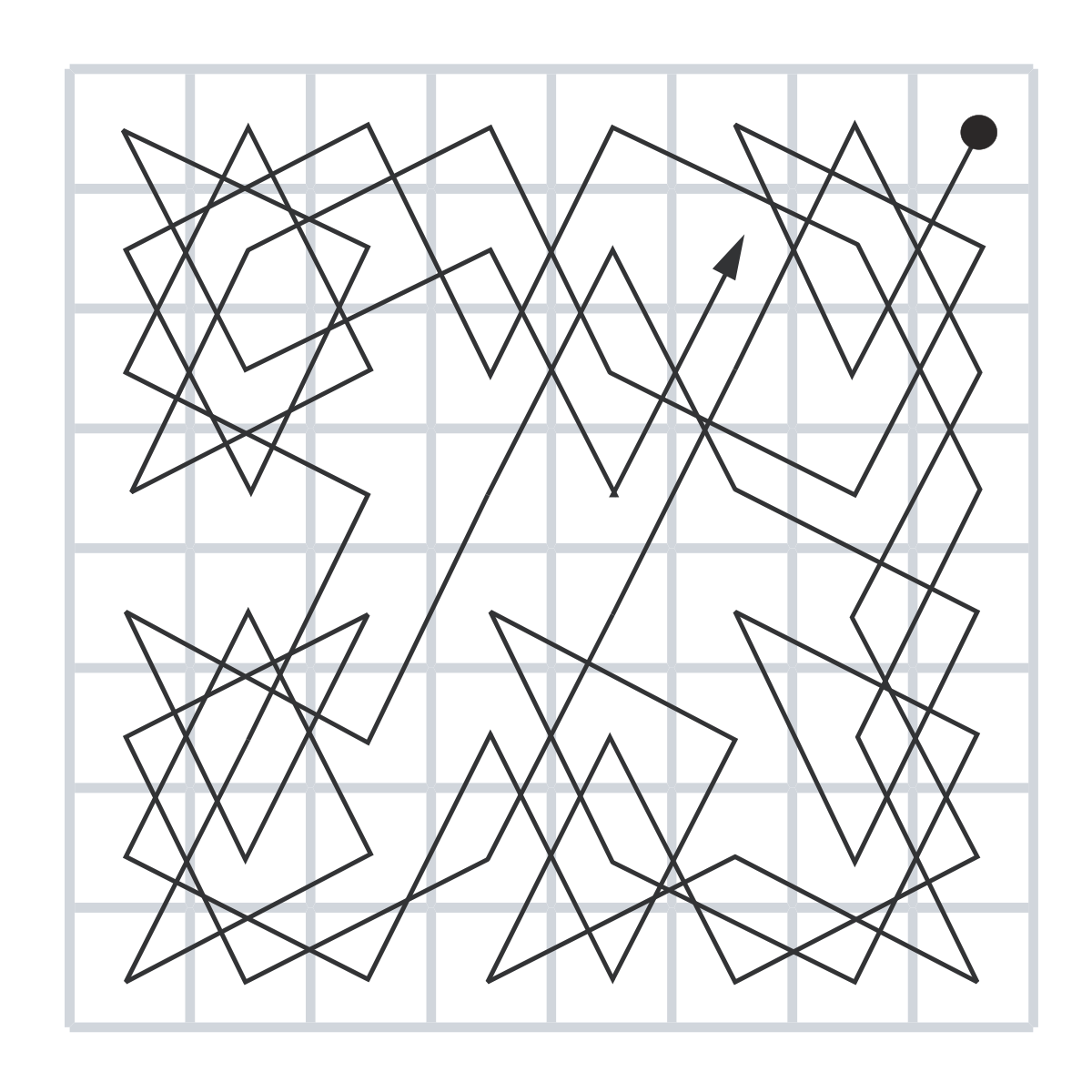

Possible Knight's Tour

The Turk Mechanics

Chess Pieces Mechanics

Turk with Man Inside

The Turk

Wolfgang Von Kempelen

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING:

PUBLICATIONS:

Levitt, Gerald M. The Turk, Chess Automaton (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000)

MUSIC:

Prelude - Filthy, Brian Lowry

Intro - Brenner, Falls

Part 1 - Fleeting, Alice in Winter

Part 2 - Hidden Beneath, Michael Briguglio

Part 3 - Morning Call, Marie

Part 4 - Birds of Prey, Wicked Cinema

Rabbit Hole - Perfect Spades, Third Age & Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES:

Wolfgang Von Kempelen -- United States Public Domain (where copyright is the author’s life plus 70 years)

Replika „Mechanicznego Turka”:

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

Creative Commons License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

Turk with man inside:

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

FULL SCRIPT

If I invited you to join me in the Marquis de Sade’s cellar, you might get a little nervous; but I promise, you have nothing to worry about. The house where he used to live still stands on the Rue St. Paul in Paris, and was there long before he was. The cellar dates back to the 16th century, and it gives you a little chill to touch the ancient stone supports. There’s so much more to Paris than the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre, if you’re willing to explore; and to stand in a space like this is to feel the city’s history in a much more potent way.

These days, the cellar is home to a pair of museums – The Museum of Curiosities and Magic, and the Museum of Automatons. Descending into an ancient cellar is the perfect way to prepare yourself to see these exhibits. They date back centuries, showing you the evolution of magical illusions, exotic artifacts that could serve as props in the telling of fantastical stories. When you look at some of these old curiosities, you can see how fundamentally simple some of the mechanisms are, how remarkably easy it is to fool the human mind. You can dismiss it as cheap trickery – a formula of engineering, sleight-of-hand, and flim-flam; but the fact that these so-called “tricks” have lasted long enough to have their own museum tells me that there’s more going on here, that something here could offer us an important historical insight. Included in the artifacts were a few items from Harry Houdini...who is a topic of an upcoming episode. Every tour concludes with a real magic show; a professional illusionist carrying on the tradition of tricking your eyes to provide delight and wonderment.

The Museum of Automatons is packed with automatons...mechanical figures that move and speak. Definitely visit our website for pictures and links. But if you need a mental picture in the meantime, imagine what Walt Disney would have designed in the 18th century - automatons were attempts to mimic human figures in remarkable ways. Really, just the first glimpse at the future of robotics...or at least robots that would mimic humans and other animals. But automatons weren’t just gifts wealthy European families commissioned and gifted to others. An automaton like some exhibited here defeated Napoleon at the height of his military and political power. But it didn’t beat him on the battlefield. It defeated him on a chess board.

You heard me correctly. A machine defeated one of history’s greatest tactical minds; and it didn’t stop there. It traveled the globe, meeting the rulers of nations, inspiring frightening stories from some of the world’s foremost authors, and may have kickstarted a world-changing invention.

How is this possible? And how is this not the most famous machine ever created? Well, in part because the story involves a lot of genius, but also a lot of the gimmickry this Museum was built to preserve and explore. Maybe the aura of showmanship stops us from giving this remarkable device the respect it deserves. I’m planning on fixing that here.

The creator of this machine was Hungarian, and he called it “A Török.” And with that, you’ve learned your first word in Magyar: one of the world’s most difficult languages. We’ll call it by its name in English. “The Turk”; and its story begins with a question that sounds like something out of a fairy tale – how do you get the attention of an Empress?

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these topics, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on instagram @mydarkpathpodcast, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. Share your thoughts about what you’re hearing, suggest a topic for a future episode or just say hi. Hearing from friends definitely makes me smile.

So, Thank you for listening. Let’s get started with Episode 12, The 18th Century Automaton Who Beat Napoleon.

PART ONE

The year is 1769. Europe is still smoldering from the remains of history’s actual first World War, the Seven Years War. Most of European politics centers around the Habsburg Empire. The Empire’s boundaries extended a little beyond the combined territory of Austria and Hungary; but the name “Austria-Hungary” didn’t come into common use for over a century. Most people simply call it “The Empire.”

It didn’t have a Death Star, but it produced more than a few inventions and innovations that changed the world. An uncanny number of creative people were born in this Empire – Josef Haydn, Franz Liszt, Mozart, a visionary you may have heard of named Nikola Tesla. And one genius who hasn’t become a household name – Wolfgang Von Kempelen.

This Wolfgang was an inventor and engineer, a man of many passions, interests, and skills. He fervently believed that the advance of science could help humanity; and he wanted to be one of the people pushing science forward. His biggest problem was that he needed a patron. Just like with Silicon Valley startups today, it’s not enough to have an idea, you need backers. Von Kempelen needed to get the attention and the favor of someone with the means to help him do his work. And when you’re living in The Empire in 1769, no one had more power and more resources than the Empress herself, Maria Theresa.

Empress Maria Theresa is a remarkable woman in the history of Europe. Her father, Emperor Charles VI, was so determined to ensure she would inherit his Empire that he issued an edict using his authority as Holy Roman Emperor. Even this wasn’t enough, and a war broke out over succession which splintered the Empire. But the Empress did a great deal in her lifetime to rebuild, unify, and modernize the territory she did control; and she even managed to maintain authority after marrying and having a male heir; not at all common back then. Also, she also showed fierce religious intolerance, and persecuted the Jewish people who lived within the Empire.

To Wolfgang Von Kempelen, what mattered was that she was the most powerful monarch in Europe, had immense wealth and influence, and she was a brilliant tactician and a savvy politician, with a real fascination and curiosity for science, a desire to keep up with the modern world. It made her the greatest patron he could possibly want. But there were countless others with the same idea. As Von Kempelen set out for the Empress’s summer residence, the grandiose Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, he knew that his biggest challenge would be just to get her attention.

Someone else is on their way to the palace at the same time, and this coincidence is what leads to the birth of The Turk. This other visitor is a Frenchman: François Pelletier. He’s an illusionist: a traveling magician, and apparently a very successful one. We don’t know many details about his act, but apparently he did some amazing things using magnets. Amazing enough to secure an invite to perform for the Empress and her court. More than once.

So, two men go to the palace. One a great scientist, one a great showman who uses a little science in his act. Who wins the attention of the Empress? It’s François Pelletier, the illusionist. The Empress is so fascinated by his performance that Wolfgang Von Kempelen doesn’t even get the chance to discuss the inventions he wants to pursue. After all, they’re only ideas, sketched on paper if he’s even developed them that far. Dry stuff, not especially inspiring.

Von Kempelen explodes with frustration and jealousy. He declares in front of Pelletier and the Empress herself that within one year, he will return with a performance that will outdo any of Pelletier’s simple tricks.

And that’s exactly what he did. And what he created, was The Turk.

***

The Turk itself hasn’t survived, otherwise it would probably be the star attraction at that museum in Paris. There are lots of drawings, etchings, sketches, and even paintings of it; and they vary in a lot of details, but this is the best collective description we can give you:

Picture a life-sized human head and torso, a figure of a man with a black beard and green eyes. He’s dressed in what audiences at the time would consider stereotypical “Ottoman” clothing: fancy robes and a turban. This head and torso are in a casual position, leaning on top of a large, white cushion. His left arm holds a long, Ottoman-style pipe. His right arm rests atop a finely crafted wooden cabinet.

The cabinet is maybe three and a half feet long, two feet wide, and two and a half feet high. It has two large doors: one each side of the cabinet, and a single drawer.

On top of the cabinet, there’s a simple but well-made chessboard, placed within arm’s reach of the Turk. When you pull open the drawer, you see that it’s lined with velvet, and contains a full set of ivory chess pieces; one set in red, and one in white. It’s a luxurious set, worth far more than the average person could afford.

There’s one last odd thing that accompanies The Turk, separate from the rest. It’s a small box, shaped like a coffin but small enough to be carried in one arm. We’ll tell you what the box is for later.

Six months after Wolfgang Von Kempelen made his promise to The Empress, he packs up the newly-finished Turk, makes a few arrangements, and heads back to the Palace. It is 1770...six years before the United States would declare independence from the British Empire.

***

Von Kempelen unveils his odd-looking machine. There are gasps. What could it be? What could it do?

He invites a volunteer from the audience to come and play a game of chess. The first person to take up that challenge is an Austrian courtier, Count Ludwig Von Cobenzi [Lood-vig von Cobenzi] .

Von Kempelen thanks the Count, and calls for a polite round of applause for the brave challenger. Then he opens one of the sliding doors on the side of the cabinet, and invites the Count to inspect the exposed, left side of the machine. The Count sees a mass of gears and weights, similar to one of those mechanical clocks that have become so popular. Then, Von Kempelen opens the other on the opposite side, demonstrating that there is nothing but else in between. No mirrors. No tricks. He repeats the action by sliding the doors shut, and then sliding them open in the opposite direction. The Count inspects the right side of the machine. Same internals. Same mechanisms.

Wolfgang then offers the Count a powerful set of magnets. Will the Count be kind enough to run them over the surfaces of the machine, to ensure that no “magnetic trickery” is involved? The Count eagerly agrees. The inspection reveals nothing.

Now, Wolfgang Von Kempelen opens the drawer with a flourish, and produces the chess pieces. The Count will play red. The Turk will play white. The Turk, as the player offering the challenge, will be given the courtesy of the first move. The Count chuckles, but agrees that this is proper decorum for a chess game.

The rules are standard. Von Kempelen promises the Count that The Turk will nod twice if it threatens the Count’s Queen. It will nod three times if it places an opponent’s King in check. But, Von Kempelen warns, The Turk does not look kindly on illegal moves.

And with that, the Turk moves! The audience is astonished, as this artificial figure of a bearded man sets down its pipe, selects a piece, and moves it. The Count answers with a move of his own, and the match is underway.

Members of the audience swear that they can see the Turk smiling or frowning. Sometimes it seems to pause in thought. When the Count does make an illegal move, the Turk shakes its head, and moves the piece back to its proper place before taking its own move.

It’s a fast, intense match. The Count, it just so happens, is an exceptional chess player. But so, it seems, is The Turk. All the while, Wolfgang Von Kempelen paces around the perimeter of the room, carrying that odd coffin-shaped box I mentioned. Sometimes he offers a witty comment on the match, and several times, he opens the lid of the little box, looks inside, and either nods in satisfaction, or makes a little tut-tutting noise.

And in just thirty minutes, the match is over. Count Cobenzi concedes defeat, and applauds Von Kempelen and his miraculous invention. The audience roars in appreciation. And the Empress Maria Theresa is impressed. With her blessing, several more matches are played, with new challengers from the court. Some lose, some win – but The Turk plays every match confidently and aggressively.

For his final trick, Von Kempelen instructs the Turk to perform one of the classic puzzles of the chessboard: the Knight’s Tour.

If you have access to a chess board, give this a try. You have to move a single knight around the board, so that it touches each square once, and only once, before arriving back at its original position. If you manage to work it out, e-mail us and let us know – we’d love to see it!

The Turk performs the Knight’s Tour flawlessly. The audience is astounded, and Von Kempelen has succeeded in his goal and then some. The Empress loves it, and he gets not only her attention, but the patronage he’d badly wanted. The Habsburgs will now fund Von Kempelen’s work.

He’s achieved everything he set out to. But he soon finds out that he may have been too successful…

PART TWO

While Wolfgang Von Kempelen guessed right that a little showmanship would help him rise above the competition, he didn’t anticipate just how popular his invention would be. The Turk becomes the talk of the court, which means it became the talk of the Empire. Everyone wanted to see it in action.

To Von Kempelen, it’s a distraction. He wants to be an engineer, not a toymaker.

He finds excuses not to put on performances. “It’s broken today,” he’ll say, or, “I’m working on a new mechanism, and I’m awaiting new parts.” For the next ten years, while we know that he did consent to private showings, he only offers one public performance: an exhibition game against the Scotsman Sir Robert Murray Keith. And after that match, Von Kempelen completely disassembles the machine. “(The Turk) is a mere bagatelle,” he says to a friend; a trifle. He wanted to spend more time on his passions – like the development of steam engines, and his dream of mechanically replicating human speech.

Unfortunately, the Empress Maria Theresa passes away, and her successor, Emperor Joseph II, is willing to continue their patronage, but on a much shorter leash.

In 1781, the Emperor orders Von Kempelen to re-assemble the Turk for a state visit by the Czar [zaar] and Czarina [zaa-ree-nuh] of Russia. The exhibition is enormously successful, which is exactly the opposite of what Wolfgang wants. Word spreads all over again. The Emperor suggests that a tour of Europe could benefit both Wolfgang and the Empire. And when an Emperor who holds your purse strings makes a suggestion, not many people are going to refuse.

The tour brings fame and fortune to Wolfgang Von Kempelen. He starts in France, with a stop at Versailles, before moving on to Paris. The Turk plays against Europe’s leading chess master, François-André Danican Philidor. Philodor is victorious, but later describes the match to his son as “the most exhausting game of my life.”

And the Turk’s last game in Paris is played against the US Ambassador to France, a man known for his scientific curiosity – Benjamin Franklin.

The Turk moves on to London, where it stays for an entire year. Next is Leipzig, then Dresden, then Amsterdam, where Von Kempelen receives an invitation to the court of none other than Frederick the Great of Prussia.

Now there’s a rumor that survives to this day that Frederick offered Von Kempelen an unimaginable sum of money for a private explanation of how the device works. We have no way of confirming it; but imagine being a scientist who once struggled to find a benefactor, having the ruler of a rival nation throwing money at you, all because of a game.

The Turk could have probably carried on this tour for many more years. But Von Kempelen, who is only human, is exhausted. He tries to find a buyer for the machine but cannot. So he leaves it in the care of the Palace, and spends his final years away from crowds, focused on his real passions. His achievements are remarkable, everything from a typewriter for a blind person, to the fountains at Schönbrunn, to his long dreamed-of speaking machine, which operates using an air bellows. He truly counts as a genius of the 18th century, an enlightened intellect who succeeded in many fields.

But when he died in 1804 at age 70, and still to this day, he is most remembered for the machine that made his fortune.

***

In 1805, Von Kempelen’s son makes another attempt to sell The Turk, and this time finds a buyer; a famous Bavarian musician named Johann Nepomuk Mälze. Mälzel, unlike Von Kempelen, is a natural performer who loves a crowd, and he intends to make The Turk his “main gig.”

But first, he needs to figure out how it works. So now, listeners, it’s time to take you inside the Cabinet, and reveal The Turk’s secrets. As you’ve probably guessed, there’s more going on than meets the eye.

First, let’s clear up our terminology. In our modern vocabulary, a “robot” is a thinking machine that can respond to a situation using its programming, while an “automaton” cannot think. It’s more akin to a mechanical puppet; and variations on such machines have existed for thousands of years. You’ve encountered automata all your life, everything from wind-up toys to the mechanical puppets at an amusement park. We definitely wrestled with the title as the word automaton isn’t common in today’s technology vocabulary.

If you went to the theatre in Ancient Greece, you might see automata at work. There’s a saying for it: Deus Ex Machina… “A God From the Machine”. It meant that if you didn’t know how to end the play, you could always depend on a spectacular special effect to close things out with a bang. Sounds like some movies we see today.

The Ancient Chinese used automatons, too: the tomb of the Ch’ing Emperor, the one with those famous Terracotta soldiers, is rumored to contain a map of all of China, with mechanically moving parts and flowing rivers of mercury.

There’s a story from the Tudor days, about a royal feast where butter and sugar were served by little wind-up carriages that travelled the length of the table. Similar expensive toys were delighting the French royals, while the peasants were sharpening the Guillotine.

In Von Kempelen’s time, one of the most famous designers of automata was a Frenchman, Jacques de Vaucanson [Jaak de voh-caa-son]. He had an automaton that could play the tambourine, another that played flute and, in 1739 he unveiled Le Canard Digerateur, or “Digesting Duck.” Yes, I said “Digesting Duck.”

This was a mechanical duck, built to scale in gold-plated copper. It could quack. It could muddle water with its bill. But what really wowed the crowds was, it could drink water and eat food, and then, it would excrete. The showstopping invention of Jacques de Vaucanson was an artificial duck who could eat and poop. People loved it!

Vaucanson was quick to admit that it wasn’t “true digestion,” what came out of the duck’s back end wasn’t what it had eaten. But he genuinely hoped that, someday, he or a successor might develop an automaton capable of fully digesting a meal. Sounds silly to the modern ear; but if you think about what he would have learned about the body’s digestive processes in pursuing this goal, it would have been incredibly impressive to pull off.

Vaucanson’s designs made an impression on Wolfgang Von Kempelen. He shared the goal of building something that would have a practical use; something that would advance knowledge while achieving a showstopping goal.

So, I’ll confirm what you’ve probably been suspecting this whole time – The Turk was not a thinking robot, it was an automaton. It couldn’t play chess itself, but it could perform the moves of the game with human guidance. But where was that guidance coming from? That’s what Johann Nepomuk Mälzel needed to figure out if he was going to make good on his investment.

And, it turns out, he’s not only smart enough to do it, he’s able to make a few improvements along the way. But before we get to that, let’s talk about what he learns when he takes the Turk apart.

It takes two people for The Turk to play a game of chess. There’s the “Host”, the showman who works the audience; and then there’s the “Operator”, the puppeteer who runs The Turk from within.

But what about that moment when Von Kempelen opened up the cabinet, and let audience members inspect the Turk’s inner workings? Well, any magician will tell you how easily such devices can conceal a person. The puppeteer sat inside the cabinet on a sliding cushion. When the Host put on a show of opening one side of the cabinet, the Operator would bend their knees, sliding back; and a false wall would drop into place, hiding them.

Inside the Turk, the Operator had several tools at their disposal. Despite the Host’s invitation to the opponent to run magnets over the cabinet in order to prove that there was no magnetic trickery, there was actually lots of magnetic trickery. He just hid it very well. The red chess pieces, which the human player would use, were subtly magnetized, and when you placed them on the board, they would attach to a series of magnetized strings underneath. When the human player moved a red piece, the strings would move, so the Operator could see their positions while hidden inside the cabinet. They controlled the white pieces using an ingenious mechanical peg board. When they pulled out a peg and placed it in a new slot, an incredibly-sophisticated mechanical device called a pantograph translated that chess move into the mechanical operations of the Turk’s left hand and arm.

If you remember that puzzle called the “Knight’s Tour”, that’s how they solved it, as well. There was a separate peg board with the solution mapped onto it, so any Operator could just follow the instructions.

I can’t stop marveling at the ideas he came up with to make this device work. He used mirrors to channel light into the cabinet so the Operator could see. The Operator could also move the Turk’s head, change its facial expressions, and perform other tricks with the left arm. The audience wasn’t imagining when they saw it smile or frown. It was all a part of the show.

And as an extra little touch I especially admire, Von Kempelen even provided a little tool that reproduced the sound of moving clockworks. The Operator could trigger it at any time, just to add to the illusion that this was a completely mechanical invention.

But what about that coffin-shaped box that he carried around during the exhibition? The one he would peer into now and again? Turns out, it was just a canard, a prop to misdirect the audience, throw them off the scent of how The Turk really worked. And it was effective; during an exhibition in an opera house, an older noblewoman insisted upon being seated as far from the The Turk as possible. Apparently, she believed that the little coffin contained some kind of malevolent spirit.

For someone who wanted to spend his life doing serious things, Wolfgang Von Kempelen turned out to be one heck of a showman. Perhaps, to him, the problem of how to engineer a human response wasn’t that difficult…once he watched that French magician at work.

Sadly, the box passes from history with the death of Wolfgang Von Kempelen, and if Mälzel received it, he never used it.

Mälzel cracked all these secrets, and even made some improvements. Instead of mirrors, which could be unreliable and required very precise positioning, he added a ventilation tube so that the operator could work by candlelight. The candle smoke escaped out of the Turk’s turban; if they were outdoors, it was too subtle to see; and if they were indoors, candles or torches around them in the room masked it easily enough. He added a letter board so that the Turk could answer simple questions from the audience; which the Operator did, in six different languages!

And he included a touch that, I think, Wolfgang Von Kempelen would have especially appreciated, since it paid tribute to his other scientific ambitions. Mälzel installed a voice box that gave the Turk the power of speech. Well – one word. When the Operator triggered the voice box, the Turk would declare “echec!”[ae-shec]; the French way of saying “check”.

So Johann Nepomuk Mälzel had his machine reassembled and improved. The Turk 2.0, we’d call it today. Now he just needed one thing – a chess player willing to sit in a cramped little box and help put on a show.

PART THREE

There were many secrets associated with The Turk; some of which we will never uncover. And one of the things we’ll never know is the names of all the chess players who collaborated with either Von Kempelen or Mälzel. They were paid not just for their skill, but for their discretion. We know that a European chess master named William Schlumberger[William scluhm-br-gr] worked for both of the original owners of The Turk; but that’s the only name we can associate with Von Kempelen’s many years on tour.

We know that during Mälzel’s European tour, he used a brilliant Frenchwoman whose name is, unfortunately, lost to history. Not only did she rarely lose, even against the most skilled of opponents, but she spoke several languages, which allowed Mälzel and herself to show off The Turk’s new ability to take questions. We know that she and Mälzel made a great deal of money together; and that it must have been a far more interesting life than 19th century Europe offered to most women. But we also know that, when there was an opportunity to tour America, she stayed behind. We don’t know what it was, but there was something in her life there she didn’t want to leave, and she had reached the limit of the travel she was willing to do.

Mälzel, however, had a great appetite for touring; and this is when the Turk’s fame really goes worldwide. One of his first triumphs? That fateful encounter I mentioned at the beginning, when the machine played against the Conqueror – Napoleon Bonaparte himself.

It’s 1809, and Napoleon has risen to the titles of both Emperor of France and King of Italy. He has just forced The Empire to sign a peace treaty after a long and vicious war, and is touring the Hapsburg territories. Mälzel seized on the opportunity to arrange for the match to take place where the world first met the Turk – at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna.

As with anything related to Napoleon, the details over the years have been obscured by a combination of propaganda, assumptions, and misreporting, but we have a general idea of what occurs.

The Turk salutes Napoleon. Then, both players are separated by a velvet rope, each seated at their own table and board. Mälzel walks between the two boards as a proctor, moving the pieces on each board.

Napoleon’s opening strategy? He breaks the rules – deliberately. He moves a piece, despite having agreed that The Turk would move first. Mälzel allows the match to continue.

Then, Napoleon moves a piece in an illegal way. The Turk responds as it always does: it picks up the illegally moved piece, puts it back in its original space, and then makes its own move. Undeterred, The Emperor makes a -second- illegal move with a different piece. The Turk moves the piece back, again, and continues.

And then, Napoleon cheats a third time. And this time, The Turk raises its head, apparently angry, and sweeps all the pieces off the board using the stem of its pipe. The audience is hushed into silence.

Napoleon? He laughs. He apologizes theatrically to The Turk, and offers to re-start the match.

I have to imagine that, as he did in war, Napoleon wanted to test his opponent before the battle got properly underway. In the second match, he plays fair. And in just nineteen moves, The Turk defeats him. In front of an amazed audience, Napoleon tips over his King and salutes The Turk. It’s perhaps the most graceful response he ever had to being beaten. There are even rumors that he came back later to test the automaton again in private.

So, what do you do when you have an invention that defeated one of the world’s most powerful people? You keep selling tickets for as long as you can. And in this case, it lasted decades; from 1809 to 1836, the Turk crossed continents and oceans. Mälzel found clever ways to keep giving opponents hope – inspired by Napoleon, he started letting them make the first move. Sometimes, he even handicapped the Turk by taking a pawn off the board before the start of the game. There are skeptics in every crowd, accusations of fraud, anonymous threats to expose the show’s secrets, but no one ever cracks the truth of how the machine works; and Mälzel and his series of operators make a very comfortable living.

And along the way, they encounter a remarkable roster of historical figures. We already mentioned Benjamin Franklin; but on an American tour, The Turk gives a performance in Richmond, Virginia that is witnessed by the legendary writer Edgar Allen Poe. He writes a long essay, “Maezel’s Chess Player”, which explores the influence of automata on modern civilization, discusses the performance, and proposes a theory about the Turk’s secret inner mechanisms. He even includes diagrams. Some of his guesses have become mixed up with what we actually know; we believe it was Poe who first proposed the theory that there was a human operator inside with dwarfism. We can’t prove a negative, so while it is possible that one of the many secret chess players operating The Turk over the years was a little person, we know that the cabinet was designed to accommodate someone of average size.

While neither Jules Verne nor H.G. Wells ever witnessed the Turk first-hand; both wrote stories inspired by second-hand accounts. The famous satirist and horror writer Ambrose Bierce wrote one of his most chilling short stories, Moxon’s Master, after learning about The Turk. In his story, a man creates a chess-playing device, and when the machine believes that its creator has cheated in a match, it murders him. This theme, of an intelligent machine turning the tables on its creator has been echoing through science fiction ever since – just think of Metropolis, The Matrix, The Terminator, Battlestar Galactica.

And here’s the encounter I think might be the most remarkable of all. A young man named Cyrus McCormick watches a performance by The Turk. Now he guesses wrong about how the automaton works; but his wrong guess actually changes the course of humanity. He believes the Turk is operated by punch cards, an idea that was beginning to show up in other technologies like mechanical looms. Some scientists at the time are even examining whether these punch cards could be used to quickly store and retrieve information.

This isn’t McCormick’s area of expertise; his family is in the business of building reapers for the harvesting of grain. But when the idea enters his head that a machine could do something as complicated as play a game of chess, he makes the leap to the idea that a mechanical reaper could increase the efficiency of any farm. The invention he and his collaborators developed helped drive the Industrial Revolution. And that’s after he guessed wrong!

And as you’ve probably guessed, there were copycats. Even if they didn’t know exactly how The Turk worked, competitors engineered their way to something similar. There was “The Egyptian”, “The Persian”. My favorite might be “Mephisto” – a chess-playing devil. He had a reputation for making rude gestures at his opponents, but would occasionally throw a match to a female player.

(Fun Side Story: Mephisto was disassembled in the 1890s and went into storage somewhere in France. His current whereabouts? Unknown. It’s fun to imagine an unsuspecting person opening an old crate in their Parisian attic and finding a chess-playing devil inside, isn’t it? Sounds like the start of a future novel!)

And eventually, technology advanced far enough that the lie could be made true. Every generation of computing has involved chess-playing machines; and finally, in 1997, the human race crossed a line there was no going back from. IBM’s supercomputer Deep Blue defeated world chess champion Gary Kasparov in a six-game match.

As for The Turk, all things must come to an end. In 1838, on Mälzel’s second tour of the Americas, his long-time operator and friend, William Schlumberger, died of yellow fever. Mälzel fell into a deep depression, became ill himself, and died at sea.

The Turk passed through a series of caretakers, winding up in a Museum owned by a collector named Charles Wilson Peale. And on July 5, 1859, a fire erupting in a nearby theatre spread to the Museum, and The Turk – the machine that dazzled an Empress, defeated a military conqueror, and inspired the great geniuses of its time, was destroyed forever.

PART FOUR

I wonder, if Wolfgang Von Kempelen could see the far-reaching impact his invention has had, if he would be so quick to dismiss it as a mere trifle. Clearly the demands of touring and performing were incompatible with his personality, but I wonder if he would be so upset now by the fact that it stands as his most famous and enduring work. It inspired so many imaginations, got so many creative thinkers trying to guess at its secrets, create their own versions. People bettered themselves because of the high bar of ingenuity that he set. We’ve seen it time and again through history, that setting an extraordinary goal can bring out the best in some extraordinary people – like when John F. Kennedy declared we were going to the moon, before we even knew how to do it.

For all the razzle-dazzle, all the trickery, and all the applause that made it all seem like a sideshow to the real science, that entertainment put science in front of the masses in a way that got them interested! That sort of power shouldn’t be dismissed; especially in the modern age as we endeavor to educate modern children in math and science. A robot duck with a working digestive system might be a lot more engaging than another textbook. I think you might be able to learn more about humanity and what drives us in Paris’s Museum of Automatons than you could learn at the Eiffel Tower. But you have to be willing to walk a dark path to get there; or in this case, down a dark stairway and wonder who else may have walked unwittingly until the Marques de Sade’s lair.

There’s one last legend about the Turk that I think sums up its hold on our imaginations. The last owner of the automaton before it wound up in that museum was John Kearsley Mitchell. He had spent years restoring the machine, even founding a chess club to help raise the funds he needed. He was near the Museum when the fire broke out, and raced there in the hopes of saving the miraculous Turk. He was too late, but for the rest of his life, he swore that he heard, quote: “through the struggling flames… the last words of our departed friend, the sternly whispered, oft repeated syllables of ‘echec! echec!’”

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host. Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a rating and review. This simple act helps us reach many more listeners. I want to welcome Evadne Hendrix to the team as producer; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by our lead researcher Alex Bagosy. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

And, dear listener, thank you. You have more choices than ever about where to spend your time. I’m grateful that you’ve chosen to spend some time here, with me walking the dark paths of the world together. Until next time, good night.

-END-